A Dream That Must Come True

Haralson Bleckley envisions a “City Beautiful” above the grimy railroad gulch

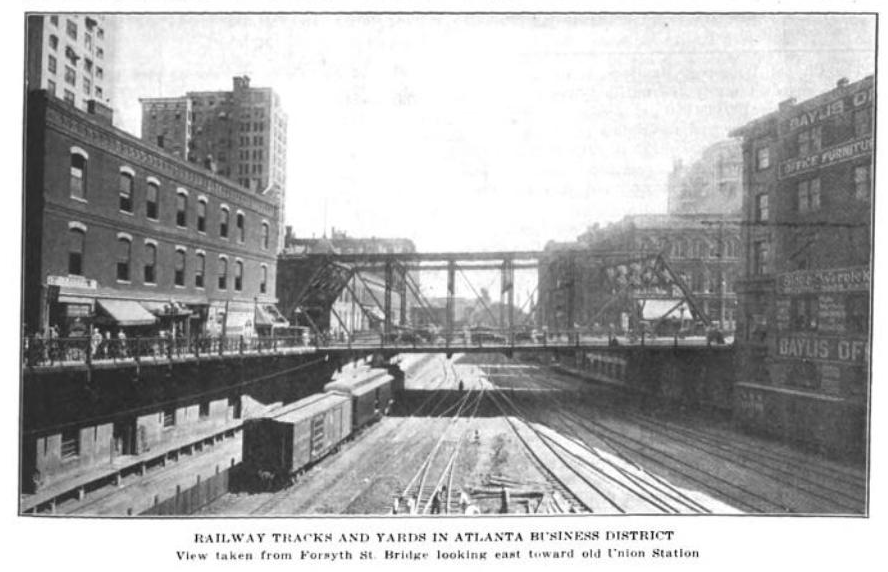

Another very Atlanta reason for elevating its streets — seen as a new city rising from the ashes of the Civil War — was a desire to rise above the city’s “grimy” and “smoky” past.

Atlanta rising above the black smoke of the railroads.

The idea of covering the railroad lines with concrete and steel platforms had captured the imaginations of city officials and the public alike. As one 1915 Atlanta Journal editorial put it, the “smoke gorge must be dealt with” – we must be rid of “railroad gulch that now gashes the city’s business center” and the “grimy chasm that scars Atlanta’s beauty.”1

While it was the railroads that put Atlanta on the map, quite literally, the idea of a pristine elevated city rising above the dirty railroad gulch and traffic nuisances had become a fascination for Atlanta’s builders. In 1915, there was even an idea being promoted in the pages of the Atlanta Journal and The City Builder that that the city should cover much of central downtown with one continuous elevated plaza.

GSU professor emeritus Timothy Crimmins and architectural historian Richard Cloues in their National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form for Underground Atlanta provide an overview of the proposed “covering” of Atlanta, noting that between 1910 and 1930 there were several ambitious plans to cover the rail lines that cut through the city.

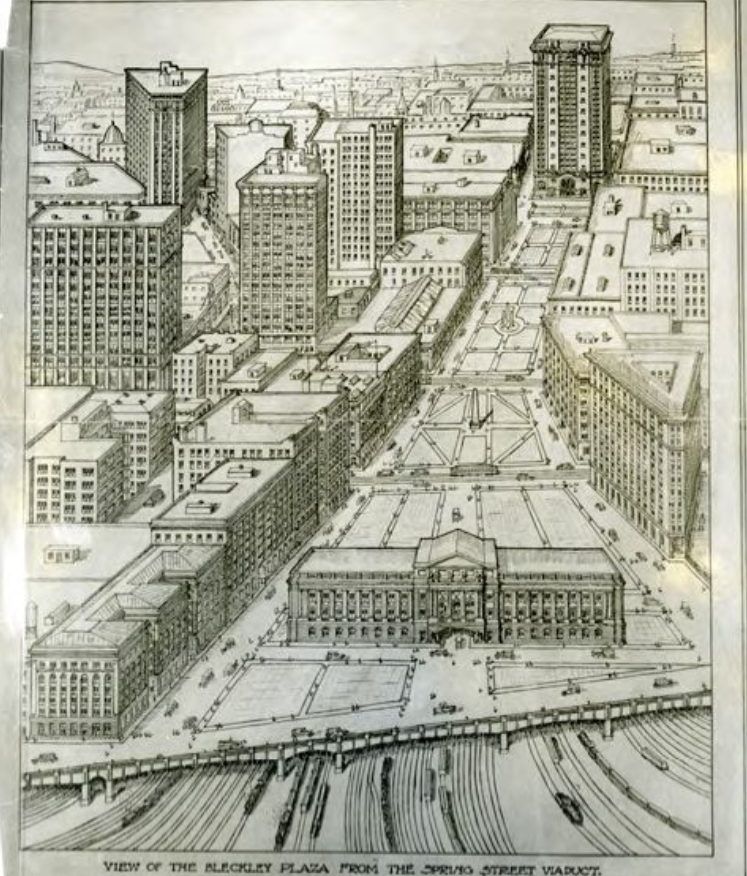

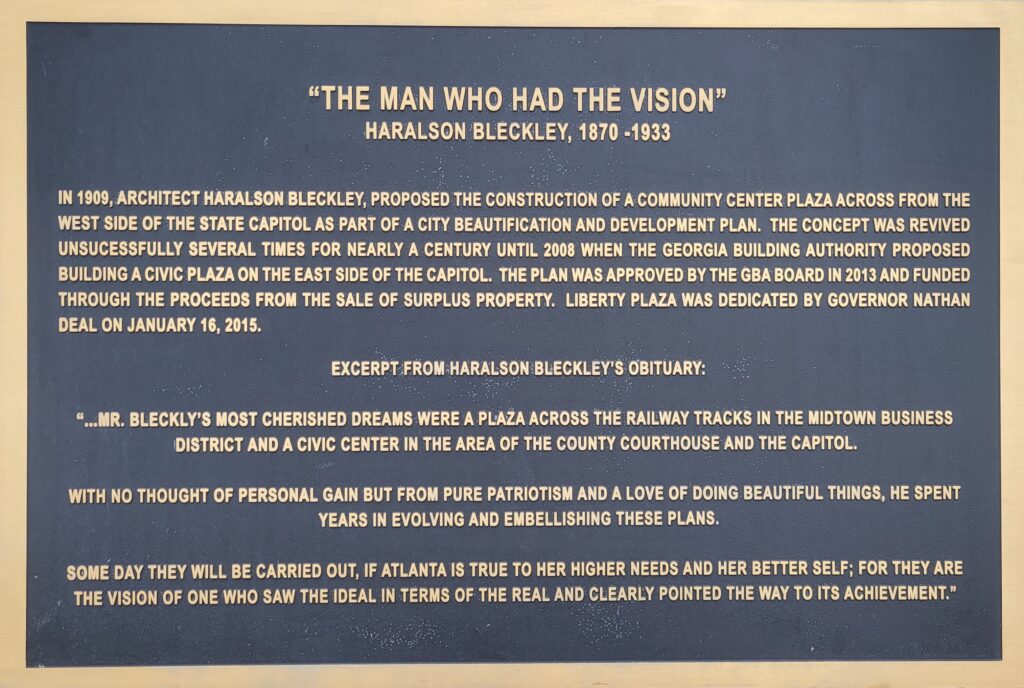

Perhaps the most ambitious plan was that of architect Haralson Bleckley, who beginning in 1909 proposed an expansive raised plaza of steel and concrete to cover downtown Atlanta east to west from the State Capitol to Terminal Station and the railroad Gulch.2 Inspired by the “City Beautiful” movement, Crimmins and Cloues write, “this was no strictly utilitarian scheme,” as it called for a series of elevated boulevards, landscaped parks, and pedestrian walkways bordered by retail shops, hotels, and office buildings above.3

The City Beautiful movement, which had its origins at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, was built on the idea that the American city should look to Europe, namely Paris, and embrace the aesthetic beyond the utilitarian in terms of architectural design. In the City Beautiful, the ugliness of a city’s slums, poverty, and smoke from railroads and factories should be out of sight and out of mind.4

It was reported that engineers believed “it would be practically impossible to properly ventilate the space beneath such a roof, so long as the railways use steam locomotives.” If parks were to be built above, trains would need to be either powered by electricity or move through single track tunnels. Estimated cost for such a project was $6,500,000 in 1916 dollars.5

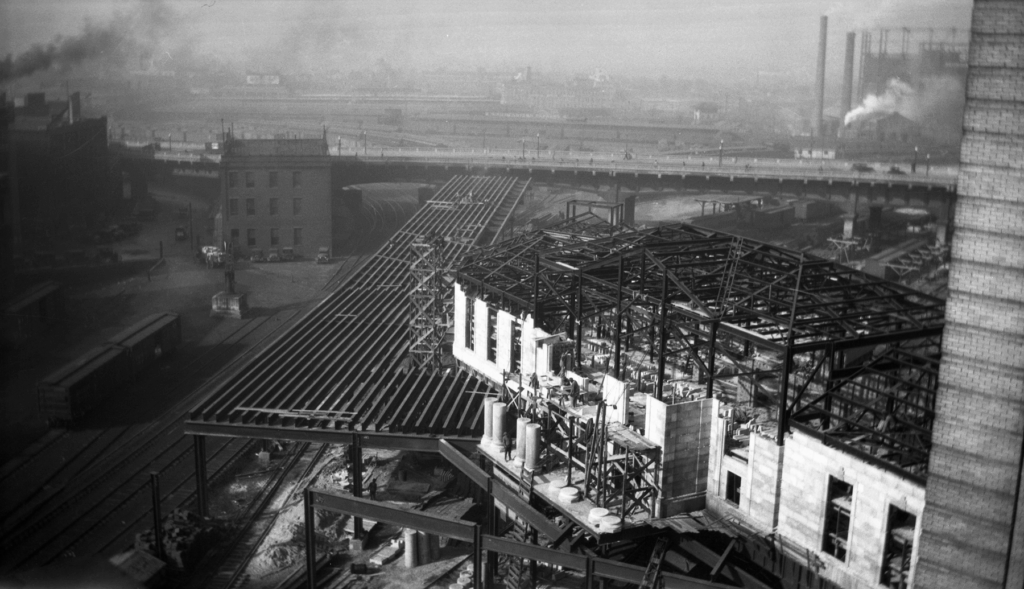

Inspired by the completion of the Central Ave. and Pryor St. Viaducts and the construction of the new Union Station between the Forsyth and Spring St. Viaducts a year later in 1930, Bleckley again returned to his vision from 20 years earlier of a continuous raised plaza that might connect these two building projects. He writes, “Imagine all of this open area of the railroad tracks being floored – what a glorious and enchanting sight it would reveal and what an ugly sore is would heal.” He again pointed out the ugliness, noise, and “smoke nuisance” of the train engines below.6

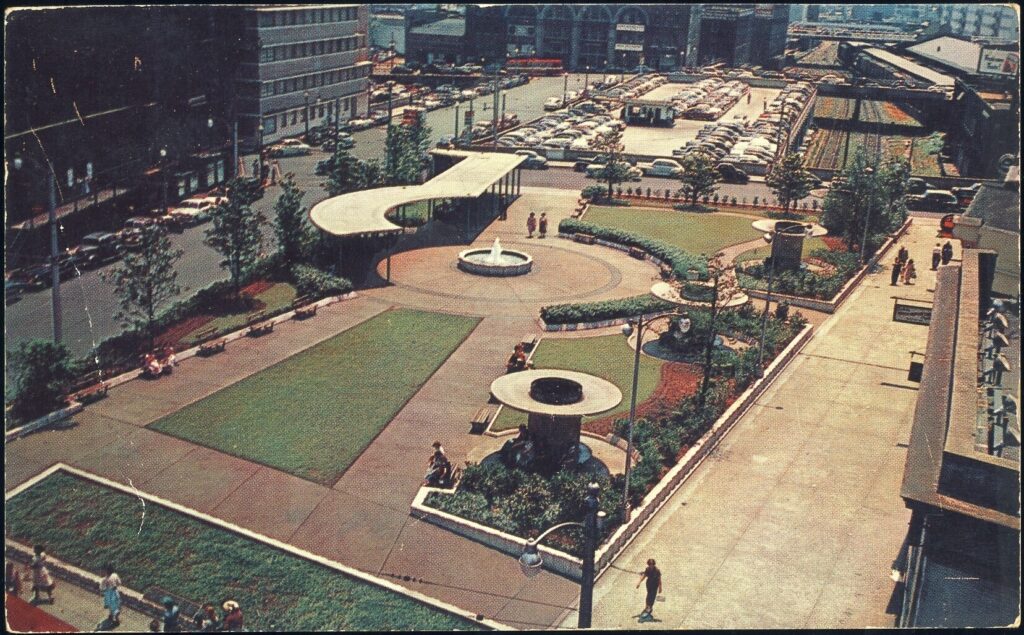

Interestingly, Bleckley had no concerns with the automobile, which he welcomed to share the parks and plazas on his raised platform city. He writes, “the parking of cars in such a large area would not in the least interfere with its adornment with flowers, shrubs, fountains, etc.,” even proposing a 25-cent fee for parking cars on the plaza in order to recoup construction costs.7

“… Mr. Bleckly’s [sic] most cherished dreams were a plaza across the railway tracks….”

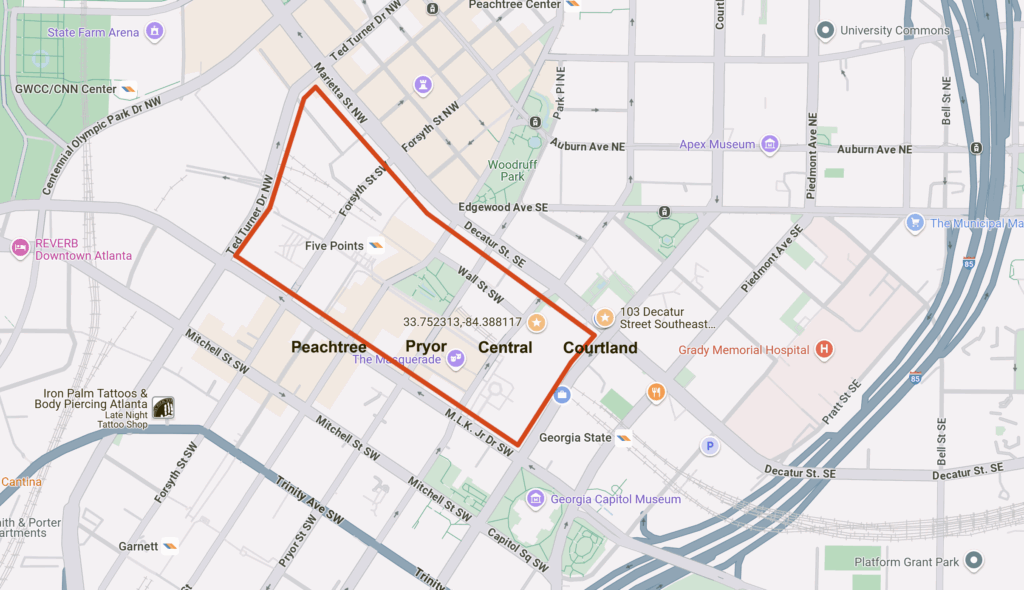

Today, Liberty Plaza located next to the Georgia State Capitol contains a plaque in honor of Bleckley. Liberty Plaza is located on the east side of the Capitol, but the architect’s vision was the platform city to stretch northwest from the Capitol (near the site of the former World of Coca-Cola museum) connecting (east to west) Central Ave., Pryor, Whitehall (now Peachtree), Forsyth, and Spring Street (now Ted Turner Dr.) viaducts.

Postcard Collection, VIS 93.046.001