Origins of Underground

The twin viaducts project of 1927-1929, and the bygone city preserved beneath the streets

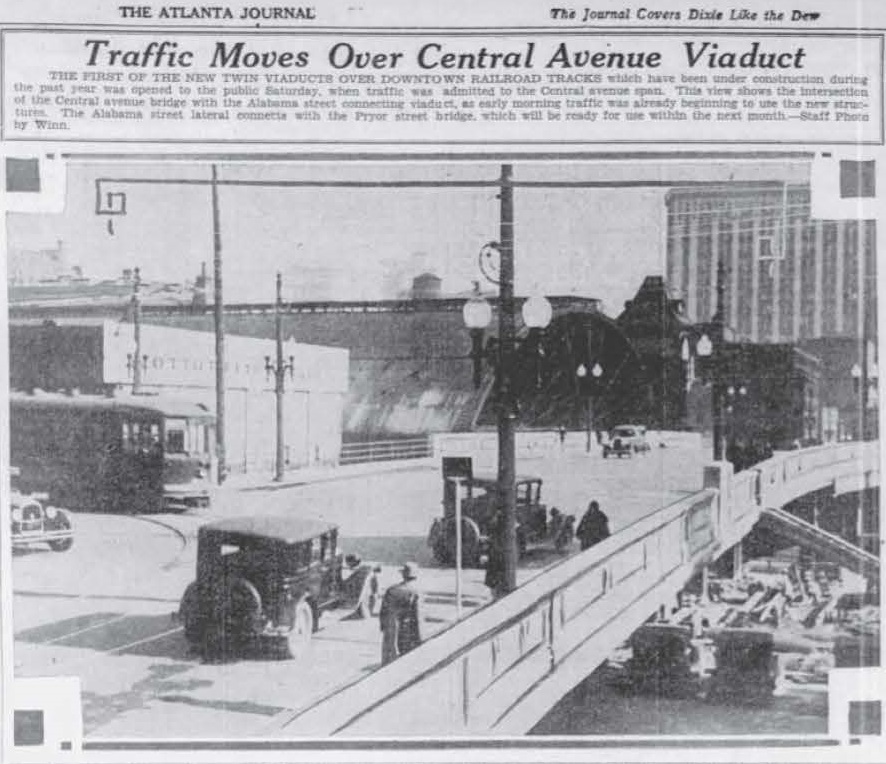

By the mid-1920s, increased traffic delays in the downtown center at the Central Avenue and Pryor Street railroad crossings near Union Station had business leaders and drivers demanding that something be done. Long before Atlanta was the city too busy to hate, it had established a reputation as a city too busy to wait!

The fast-moving automobile and slow-moving locomotive were constantly at odds, with multiple commentators in The City Builder complaining of the gridlock during so-called “rush hours” and advocating for the construction of more viaducts over the railroad tracks.1 Writing in 1927, the Chairman of the Viaducts Committee of the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce stated:

Traffic congestion has become the outstanding problem of the modern city. The motor car and its steadily increasing use has upset all calculations for city builders. ‘Bottle necks’ where the flow of traffic reaches its greatest congestion, exist in virtually all cities. It has become especially acute in Atlanta.2

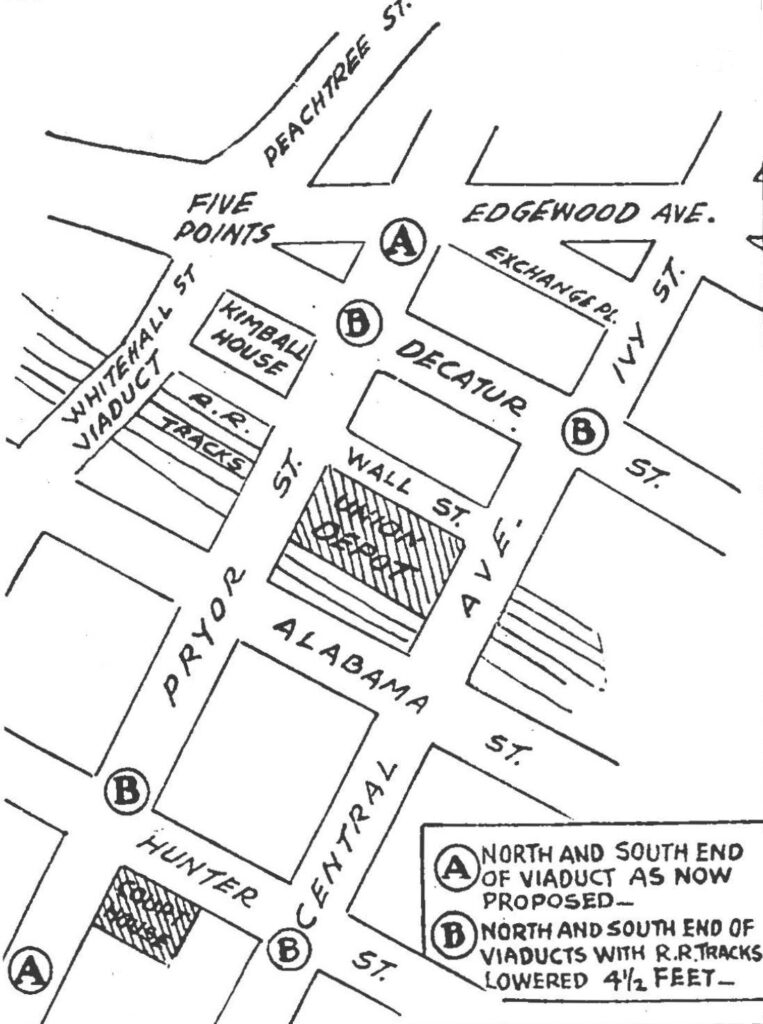

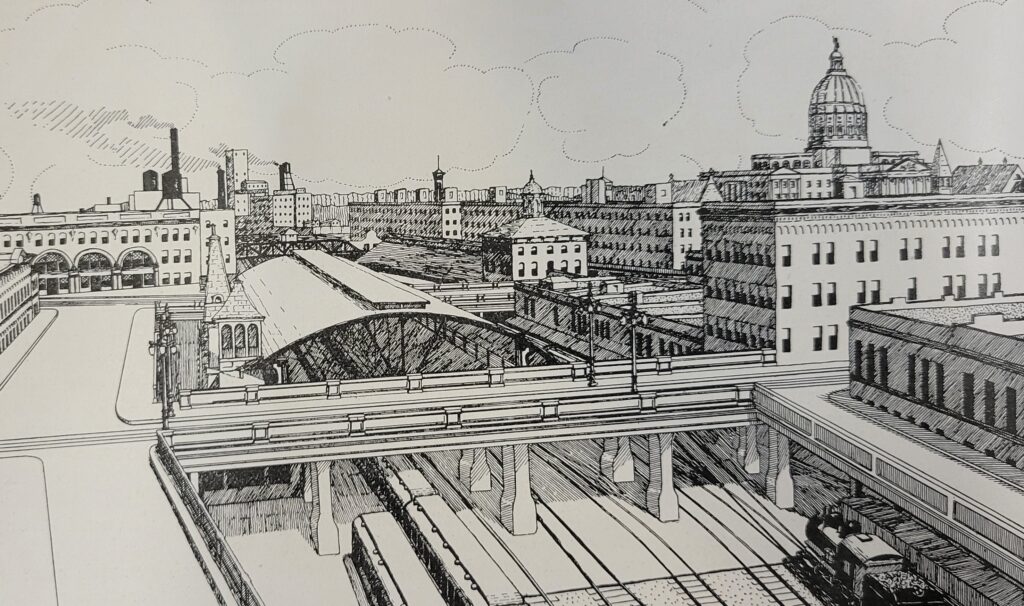

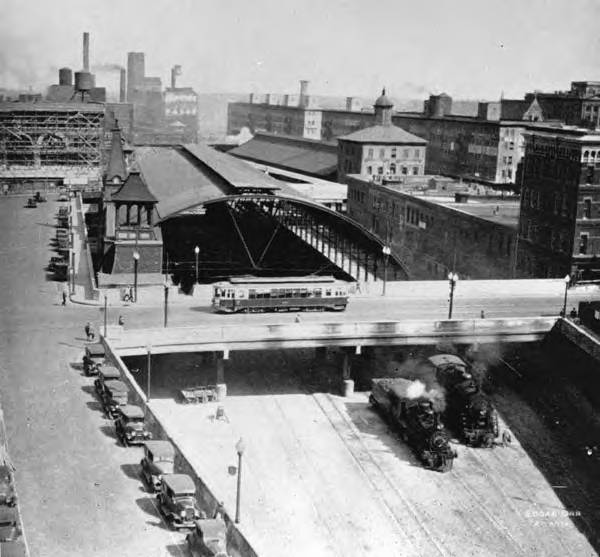

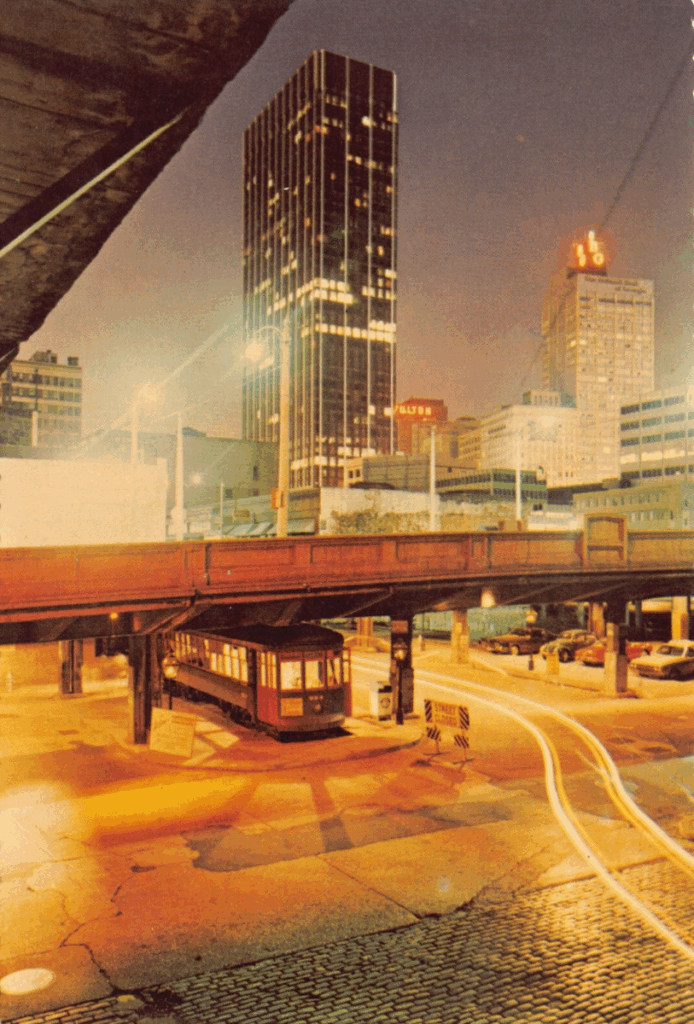

The “twin viaducts” project of 1927-1929 would attempt to alleviate congestion for the entire commercial district around what was then Union Station (1871-1930).

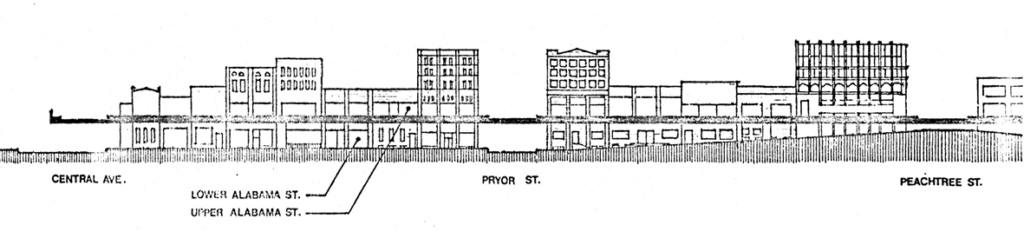

The project would elevate the street levels of Pryor Street and Central Avenue running north to south (the viaducts), as well as raise Wall and Alabama Streets (the “laterals”) providing a seamless grid of concrete platforms for streetcars, automobiles, and pedestrians traveling east and west between Central and Pryor and connecting the area with the Whitehall-Peachtree Street Viaduct.

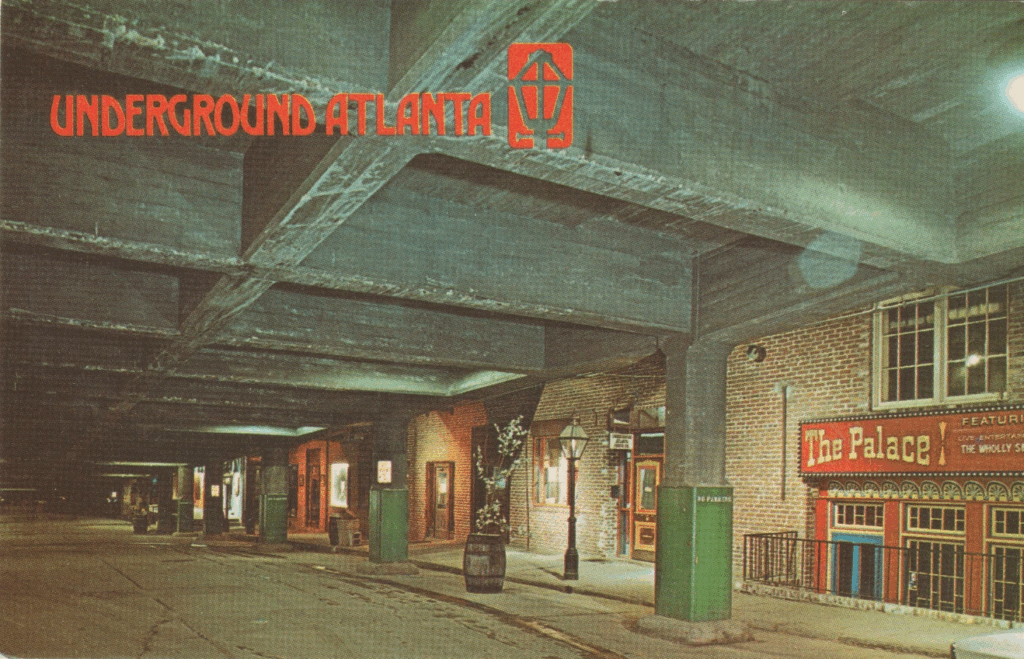

“This project quite literally entombed the original ground-level streets and storefronts below. What remained underneath would become what we now know as Underground Atlanta.”3

As Bryan Sinclair notes in his photo essay “Before Underground,” this was a new city readying to move on and up to something new. Photographs from this period available from GSU Library’s Digital Collections depict many business along these streets advertising moving sales and posting their new addresses in shop windows.4

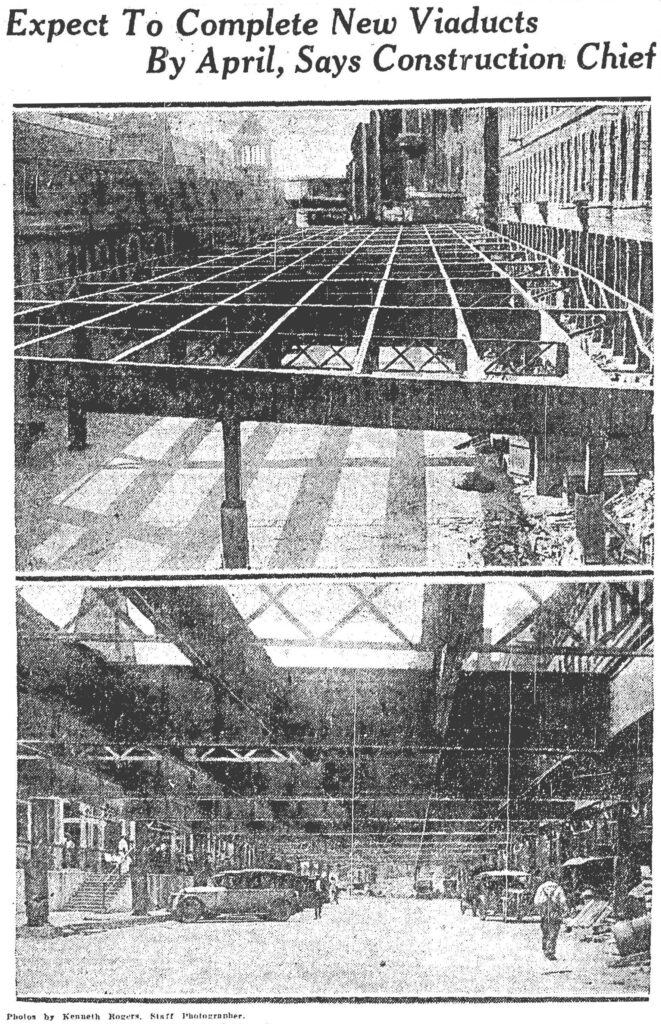

Preparing for the Covering

The two images below show the excavation work on Alabama Street in 1927 in preparation for the street covering. Both areas can be found in Underground Atlanta today as Lower Alabama Street — on the left, looking west from Pryor Street, and on the right, looking east toward to the future Central Avenue Viaduct and Georgia Freight Depot, whose main level still stands today as Atlanta’s oldest existing building.

The plan was for storefronts and businesses to move their main entrances to the platform streets above, leaving the story below as a service entrance for deliveries with ample height for delivery trucks. The streets would need to be raised in some areas and lowered in others in order to accommodate motor traffic underneath. Up and down Alabama Street, modifications and upgrades to underground electric cabling, gas mains, sewers, and other improvements were required before construction could begin.

Similarly, concerns regarding drainage and grading would need to be addressed. Alabama Street would need to be elevated where it met Pryor Street, making it level with Whitehall Street (now Peachtree). In other sections, the brick paved street would be torn up, lowered several feet, and then repaved in order to maintain clearance below. At the same time, extensive excavation would be required to lower and relay the tracks for rail clearance beneath the viaducts.5

Old Atlanta reborn …

Beneath these elevated streets, blocks of old Atlanta would be abandoned and mostly forgotten for four decades — that is, until the 1960s, when a group of Atlanta visionaries led by Architect Paul Muldawer, GSU art professor Joseph Perrin, and associates at the Civic Design Commission had an idea.

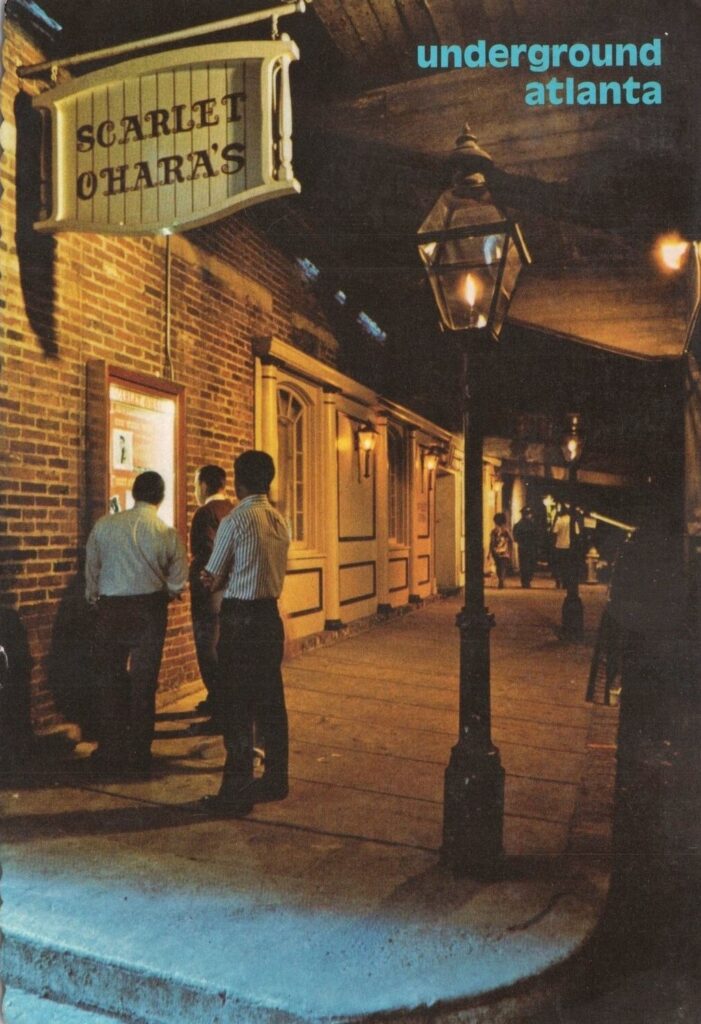

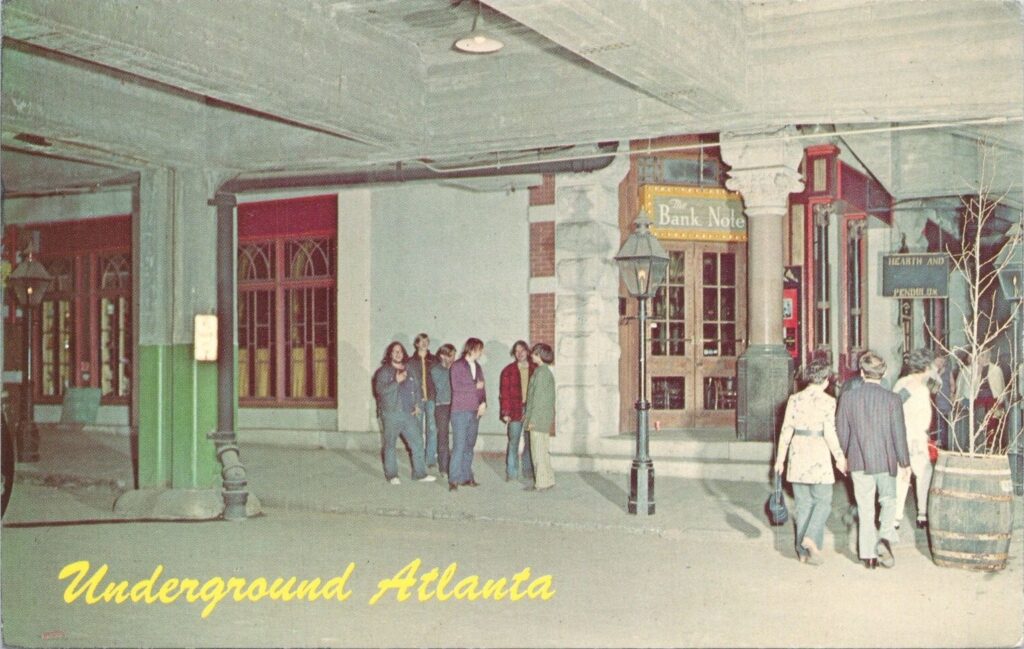

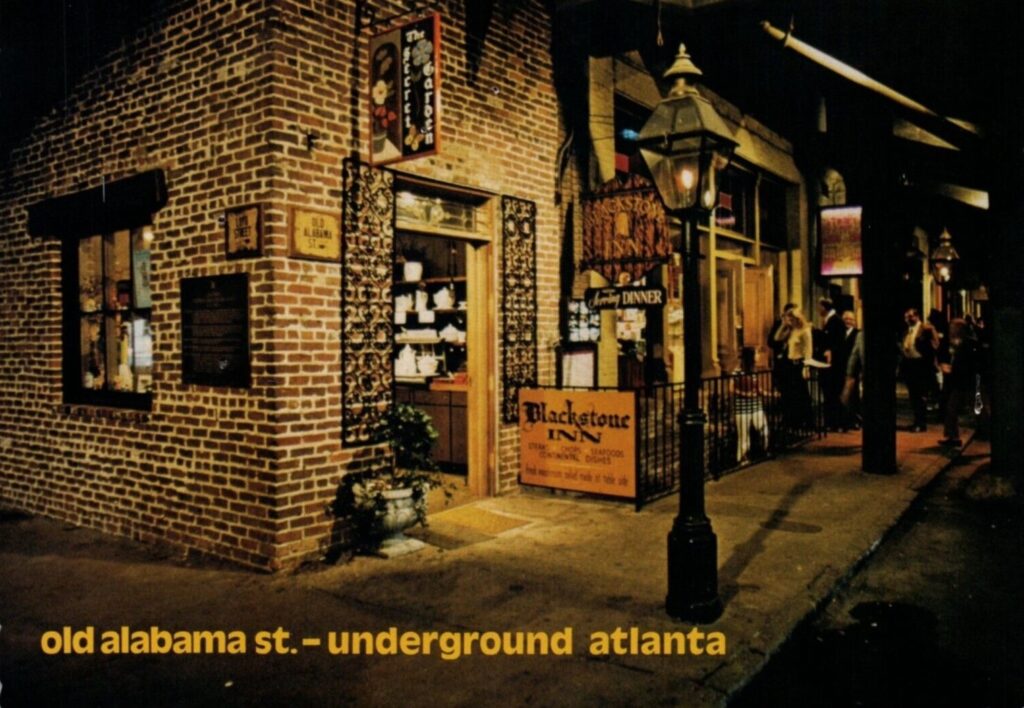

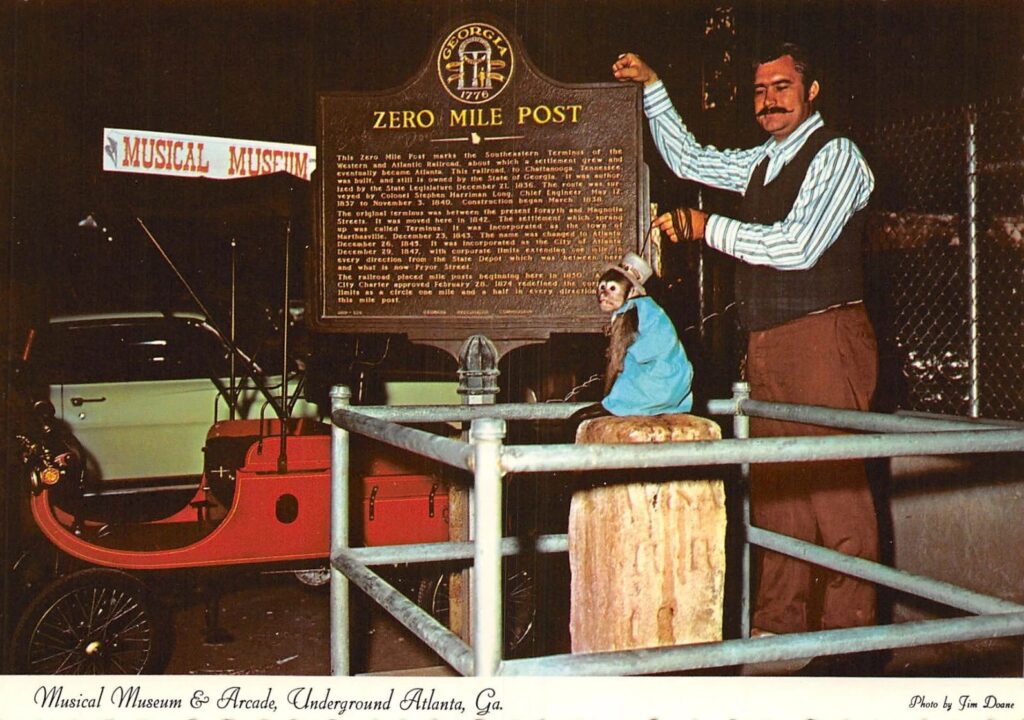

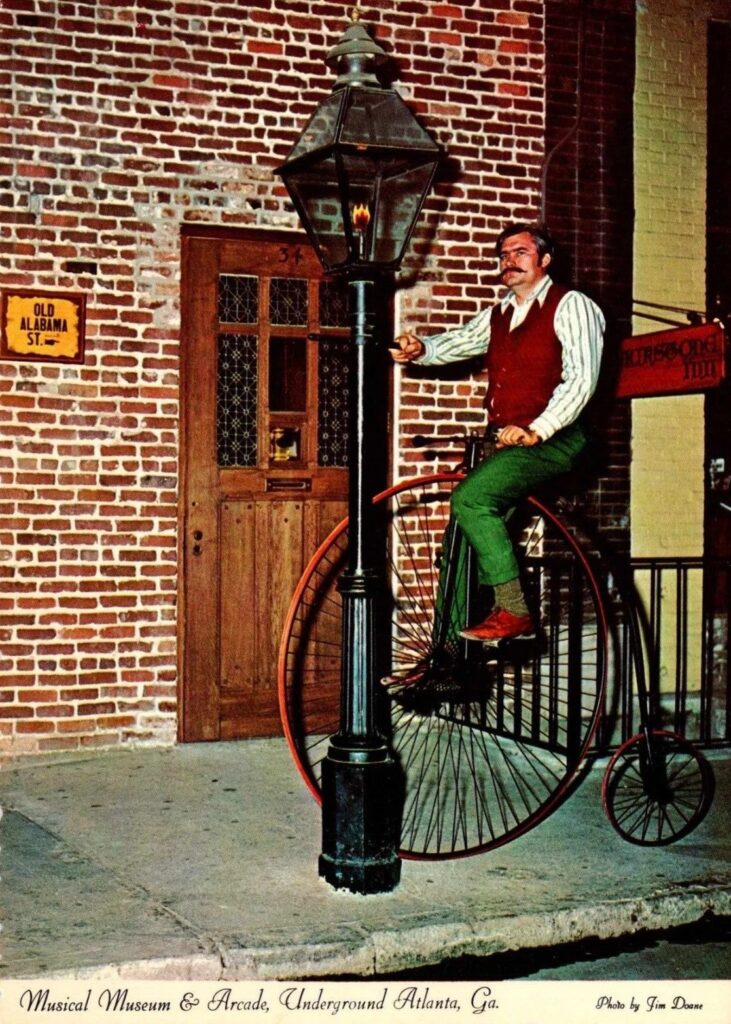

What others saw as grimy and unappealing, they saw as having tourist potential: an “Underground” beneath the streets reimagined it as a nostalgic attraction reminiscent of the French Quarter in New Orleans and Gaslight Square in St. Louis.6 The downtown attraction that we know as Underground Atlanta would first open to the public in 1969.

… and then almost lost again

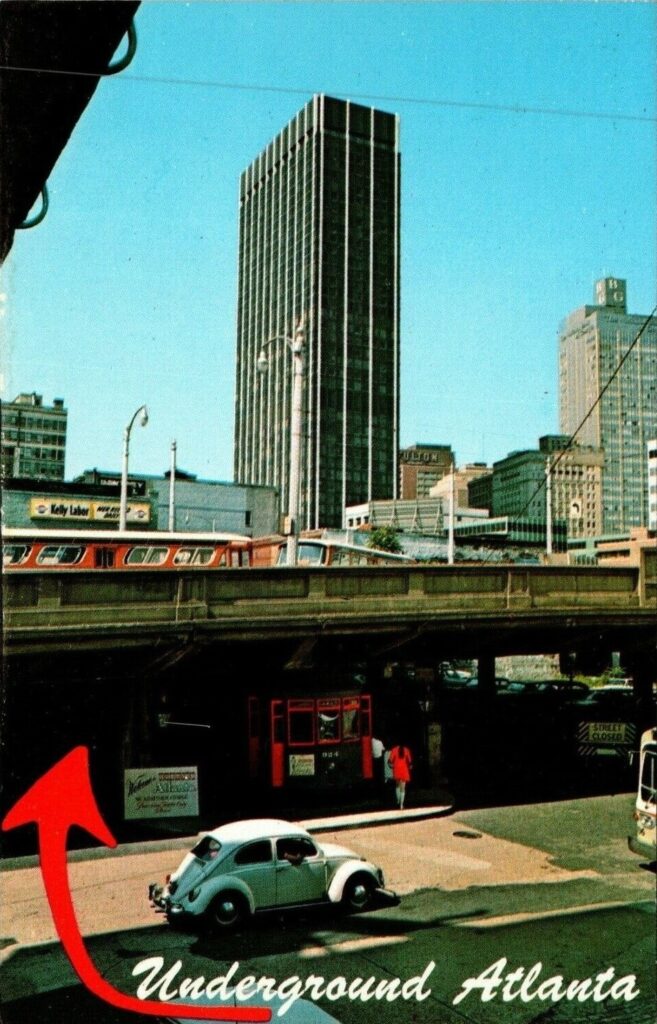

The (first) real heyday of Underground Atlanta, with its gas street lamps, numerous live entertainment venues, restaurants, bars, and shops was relatively short-lived, lasting from 1969 until around 1975.

In 1974, the new Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) announced its right of way plans to take out almost a third of Underground’s original footprint to make room for its new rail lines. This would force some 15 popular Underground night spots to relocate or close.7

Underground rebounds

Underground Atlanta has had many lives since it first opened in 1969. As of 2024, Atlanta-based Lalani Ventures and partners are currently transforming what was (once again) a largely abandoned site into popular mixed-use arts and live music destination. The ultimate plan is to create a multi-level complex with housing, office space, retail, restaurant, and art studio space, complete with a new hotel and community space including green pedestrian plazas.8