Recent Lofty Visions

The 1970s through today – future concepts, Centennial Yards, and The Stitch

The 1970s marked a time of new possibilities for the modern city. Visionary Atlanta architects like John Portman (1924-2017) were imagining a new Atlanta as a dense urban complex just north of the downtown district at Peachtree Center, connected with enclosed pedestrian skybridges suspended above the street level.

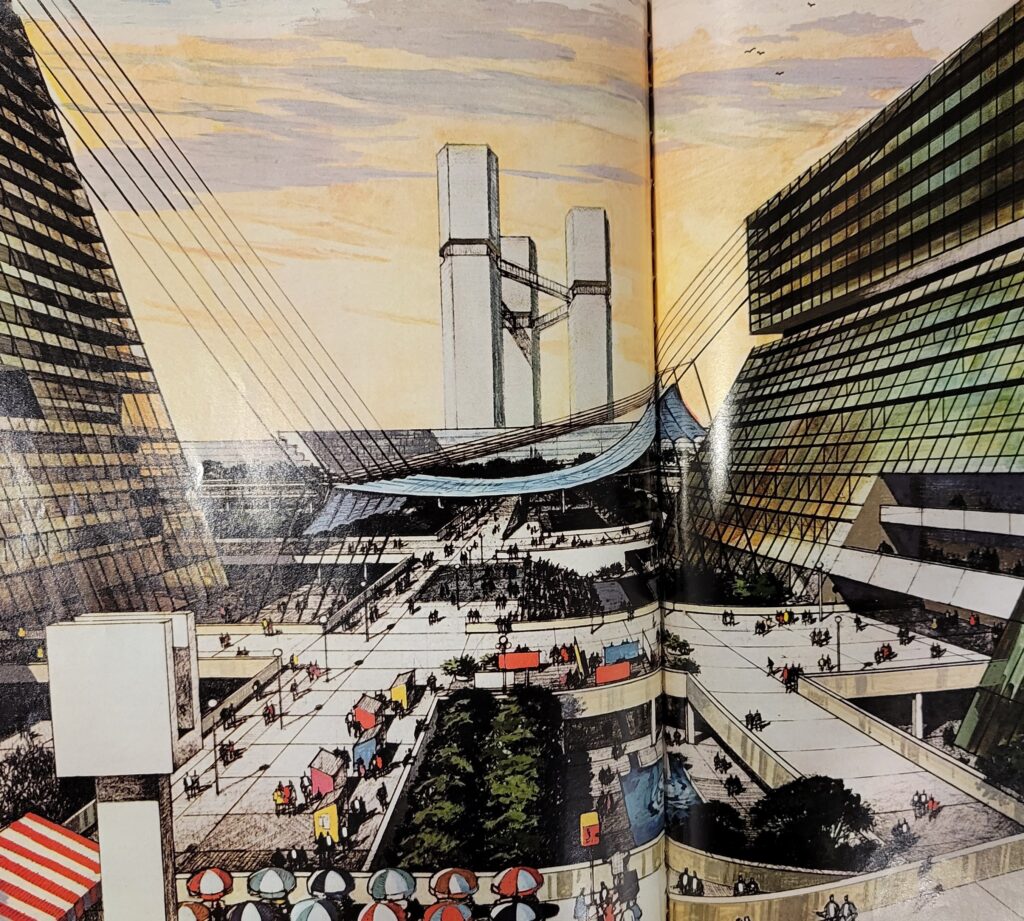

In 1973, Atlanta magazine invited various architects to envision downtown Atlanta in the year 2000. The issue featured many bold and futuristic ideas for the modern city, including the ultramodern concept below from Atlanta architects Finch, Alexander, Barnes, Rothschild and Paschal (FABRAP) who envisioned a pedestrian-centered platform city straight out of science fiction.1

Centennial Yards

Today, the elevated city still wrestles with what is to be done with “grimy” railroad gulch that cuts through its downtown, same as it did over a century ago. The latest plan is for a 50-acre “urban revitalization project” called Centennial Yards, an ambitious $5 billion project anticipated to transform the long-abandoned gulch into a “thriving community with leading businesses, retail establishments, a world-class entertainment district, and thousands of new apartments designed to develop a diverse, collaborative, and inclusive community.” On its website, the Centennial Yards Company pays homage to Atlanta’s railroad past as it evokes a bright future, linking the city’s industrial past to its progressive spirit and innovation: Atlanta’s bustling railroad yards of the past transformed into a futuristic urban complex.2

Centennial Yards may be seen as an extension of Haralson Bleckley’s elevated plaza visions and the viaduct projects from a century ago. In many ways, this project shares a similar vision as it aspires to connect people and drive commercial progress on the elevated city above.

The Stitch

As we conclude this exploration of Atlanta, the elevated city, one additional project deserves some attention. The Stitch is another ambitious plan, this time to cover and contain the noise, pollution, and congestion of the multilane I-75/I-85 Downtown Connector with a series of raised parks and plazas.

Once implemented, according to its website, The Stitch will create approximately 14 acres of urban greenspace and transportation enhancements atop a new, ¾-mile platform intended to “restitch neighborhoods torn apart by downtown freeway construction.” This $700-million project may actually come to fruition as federal infrastructure grants have been awarded to begin the design process and first phase of construction.3

While similar in vision to the raised platform projects that came before it, The Stitch may represent a new chapter for the elevated city. It is not a strictly utilitarian initiative like past projects to address traffic congestion, nor is it driven mainly by aesthetic concerns, although those are certainly part of it. Its website describes it as “transformational civic infrastructure investment” to build community, “restore human-scaled connectivity,” and promote economic development and healthy lifestyles, among other ambitious and worthwhile goals.4 It may also be seen as a city’s attempt, if only symbolically, to correct past wrongs done to its fellow citizens.

“Restorative Benefits”

The Stitch Master Plan addresses the project’s “restorative benefits” for its surrounding communities, namely the impact on former Black residents and their decedents caused by urban renewal and interstate highway projects.

Some context:

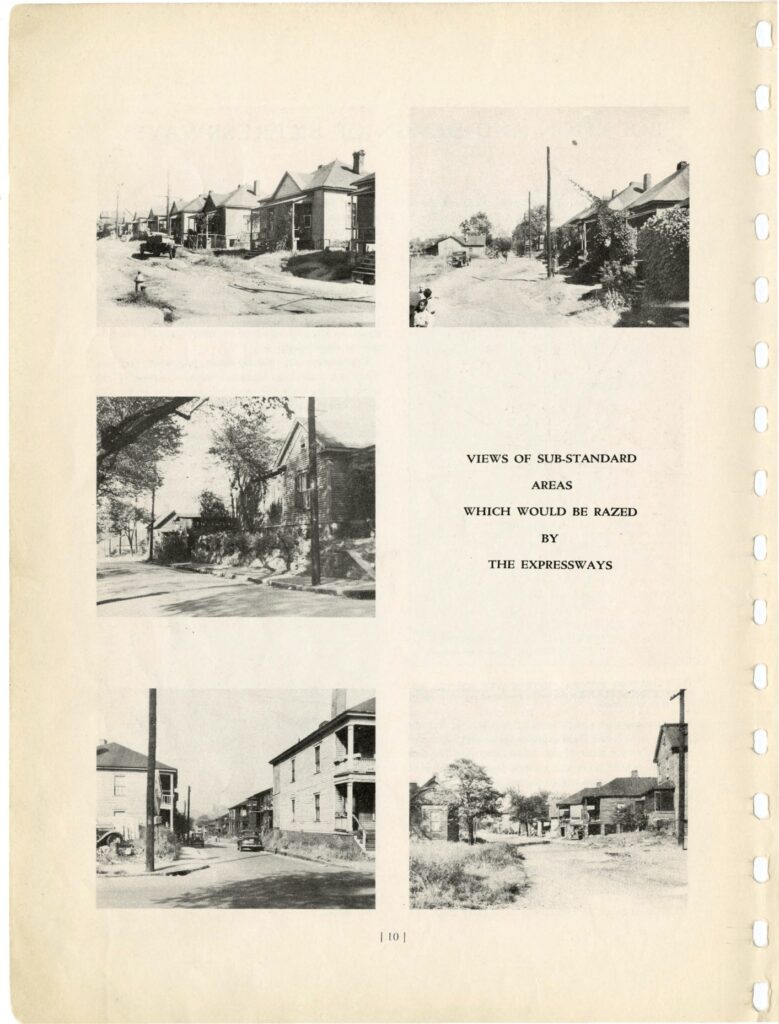

Between 1948 and 1964, the multi-lane interstate projects that created what we know as the Downtown Connector cut through the city’s center separating and, in some cases, bulldozing established Black communities. Sponsored by the federal government, the path it cut was largely determined by local officials who intentionally steered the project through “blighted” Black neighborhoods.5

Communities directly impacted included Buttermilk Bottom, the Bedford-Pine community, as well as the Butler Street community to the west and the Sweet Auburn business district. Family houses were demolished, thousands of Black Atlantans displaced, and established communities were cut off from each other.

Writing in the state and federal joint highway plan that proposed the Downtown Connector:

The neighborhoods in Atlanta through which it would be feasible to purchase suitable rights-of-way, being the most depreciated and least attractive, are most in need of this rejuvenation. The urban sections of the expressway would be largely of the depressed type.6

Conclusion

Earlier in this exhibit, we discussed the City Beautiful movement of the early 20th century that dreamed of projects that would rise above the grimy, less appealing aspects of downtown. By the 1940s and 1950s, as attentions turned to the suburbs, planners turned their focus to a different type of building project, namely the raised highway that would move people and their cars away from the central city and its “least attractive” features. And while they were at it, those “most depreciated” neighborhoods which were “largely of the depressed type” could be conveniently bulldozed away. If it comes to pass, The Stitch will not correct these wrongs, but there is an optimism in its vision: one that acknowledges the mistakes of the past and recognizes the harms of urban renewal and the interstate system that cut through the city, as it seeks to “stitch” Atlanta communities back together.

To once again quote the editorial pages of the Atlanta Journal from 1915, in support of Bleckley’s raised city plaza, we may once be rid of the “gulch that now gashes the city’s business center” and the “grimy chasm that scars Atlanta’s beauty.” Like in 1915, the dream of a city rising above its past remains, and Resurgens (Latin for “to rise again”) remains a most apt city motto.

Exhibit last updated May 2025

See updates