Rise of the Viaducts

Building projects address gridlock and safety in a growing city on the move, 1880s-1920s

Atlanta is a city of viaducts. Established by the railroads in the 19th century and transformed by the automobile in the 20th century, Atlanta was built first for the movement of goods and then for people, not unlike most industrial U.S. cities. In Atlanta, this included the construction of a series of viaducts in the central business district that grew up around the railroads. But what is a viaduct, you might ask? In our case, it’s a bridge or elevated platform spanning the railroad tracks that allows for the movement of cars, pedestrians, and, up until a period, streetcars that crisscrossed the city.

While the city would not have existed if not for railroads, the train traffic cutting through the heart of the business district presented a constant headache for city planners and businesses. Atlanta would see tremendous population growth in just fifty-year period: from ~3,700 persons in 1880 to over 270,000 in 1930, and based on the photographs here, everyone was on the move. Not only did rail traffic impede the steady movement of wagons and merchandise across the numerous rail crossings, there were also significant safety concerns and inconveniences for pedestrians.

Some of the first attempts to alleviate these inconveniences included the construction of the Broad Street viaducts of 1873 and 1895 and Forsyth Street viaduct of 1893. But it was not until 1898 that the city of Atlanta began to earnestly ramp up plans to cover the railroad tracks; that year, the Mitchell Street viaduct would be completed opening access from downtown to the West Side.1

The Peachtree-Whitehall Viaduct

The most significant viaduct project would come at the dawn of the 20th century: one that would transform the downtown by connecting the north and south sides and address what was perhaps the most dangerous intersection for wagons and pedestrians crossing at the heart of the city.2

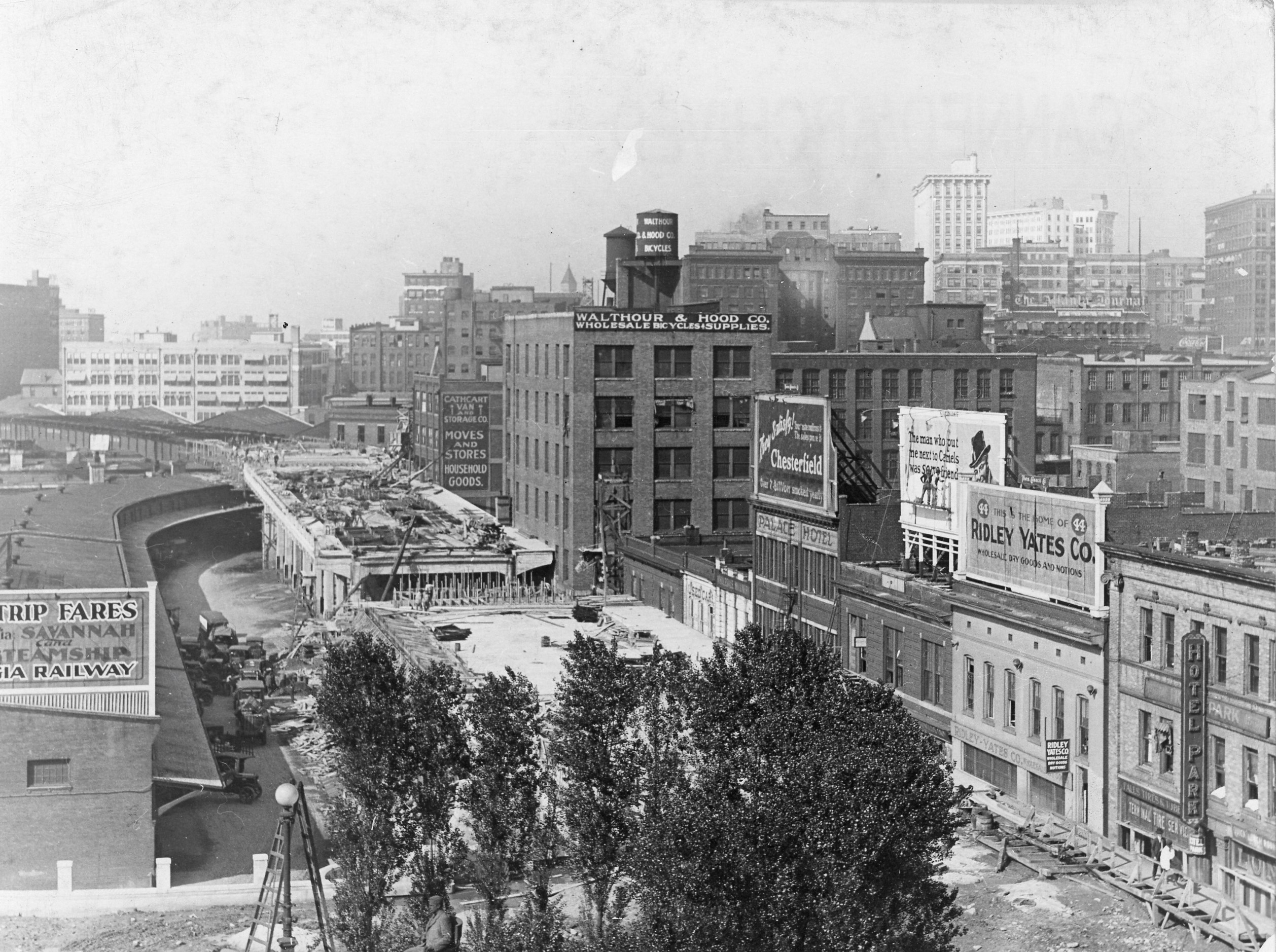

Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives, AJCP338-035q. GSU Library Special Collections & Archives.

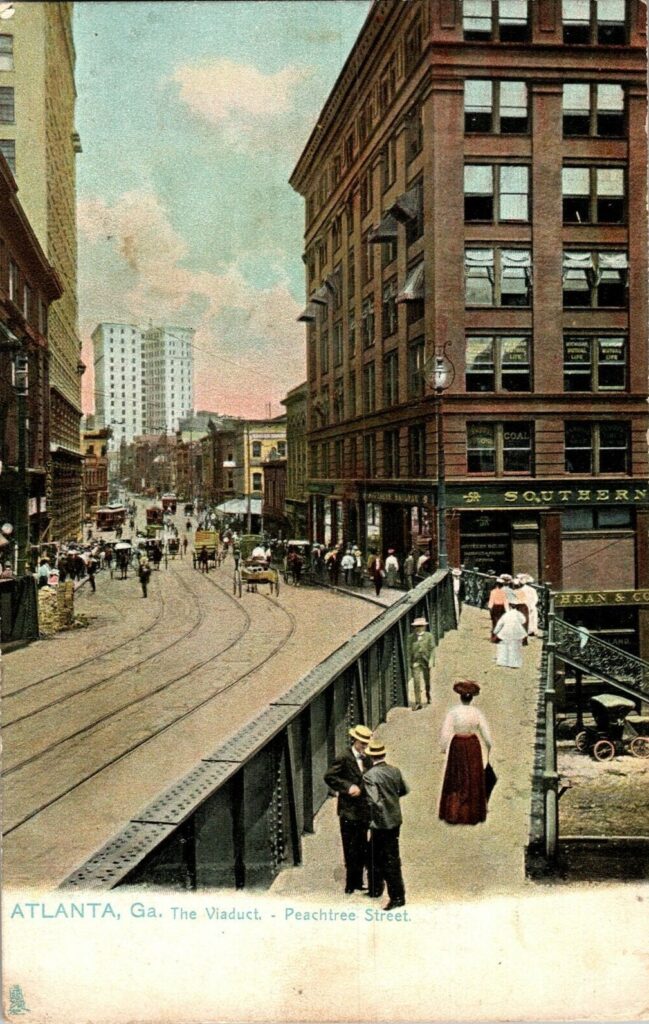

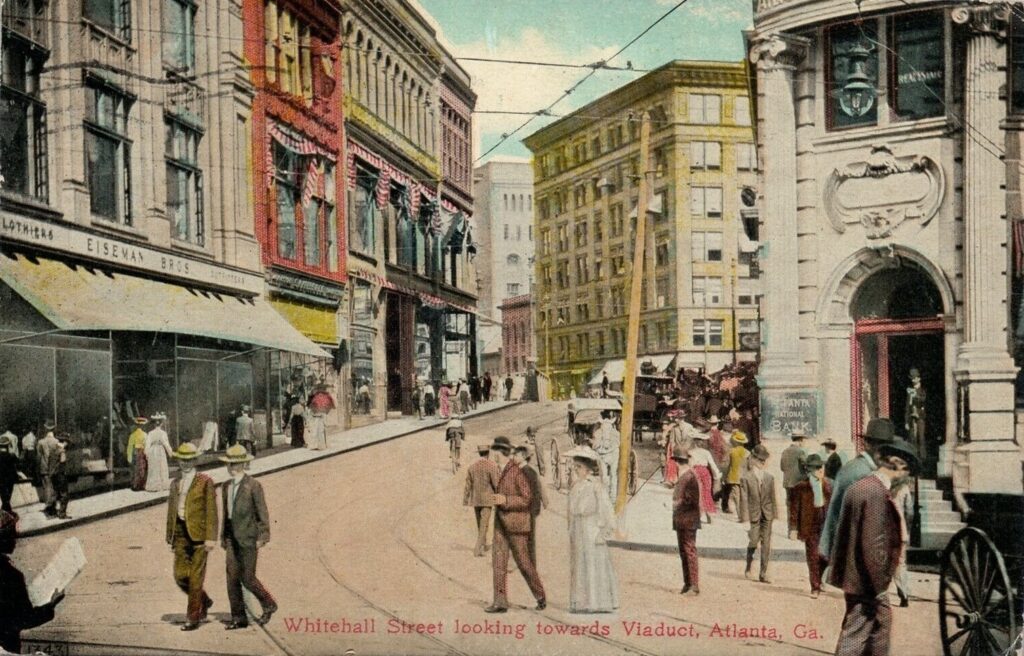

Construction began on the Peachtree-Whitehall Viaduct in 1900. Upon completion in October of the following year, this important connector was an immediate success for everyone: business owners, pedestrians, streetcars, and eventually automobiles, which could now pass safely across Whitehall Street to the south and Peachtree Street to the north. Atlanta now had its main street — its “Great White Way.” Postcards from the time depict men in boater hats and women in white dresses parading up and down the sloping street, removed from the smoke pollution and dirty engines below.

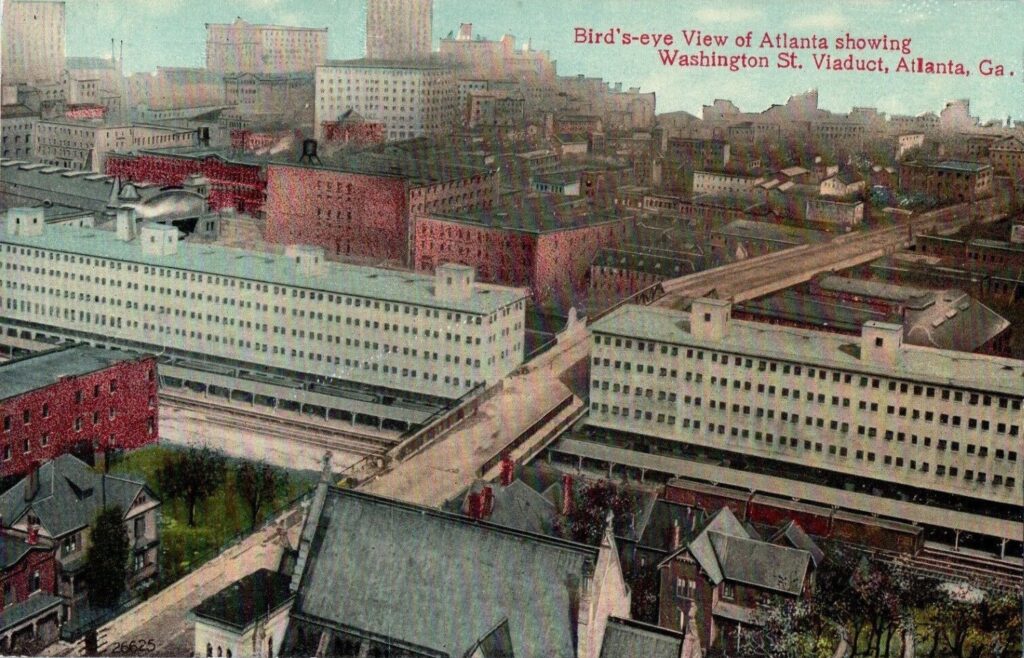

GSU Library Special Collections & Archives.

More Viaducts Follow

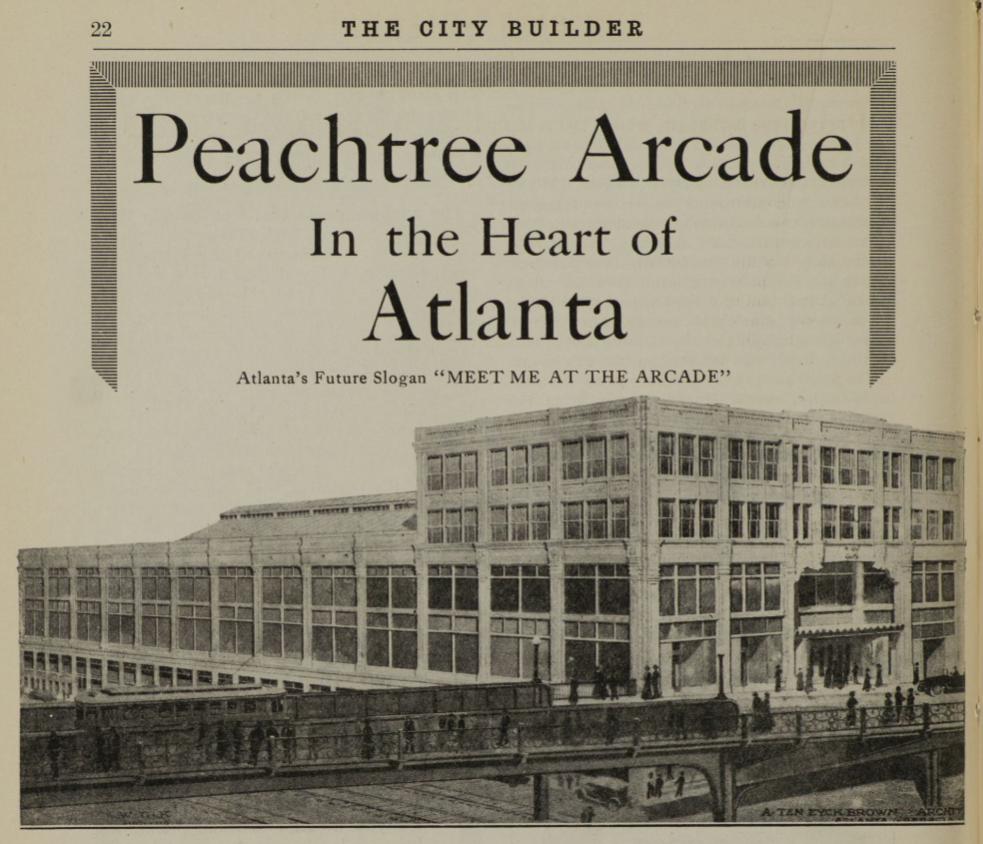

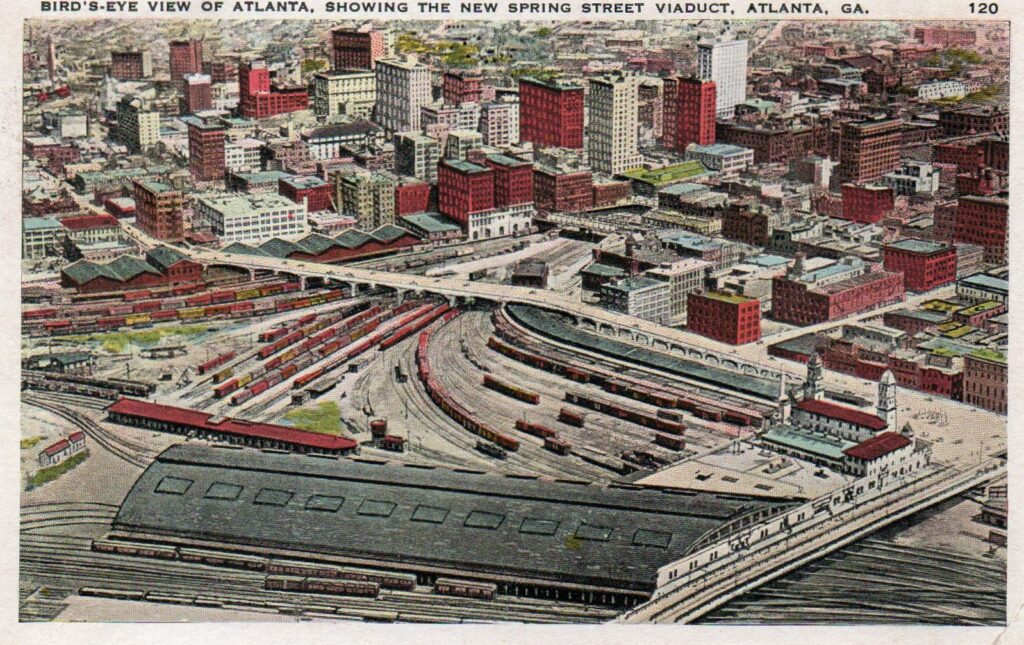

With the success of the Peachtree-Whitehall Viaduct, other viaducts would soon follow including Washington Street (now Courtland Street) in 1907 and the impressive Spring Street Viaduct (now Ted Turner Drive) in 1923, which connected Spring Street to the south with Madison Avenue to the north “creating the longest expanse covering the railroad tracks to date.”3

GSU Library Special Collections & Archives.

Viaduct Blues

The Washington Street (now Courtland Street) Viaduct project of 1907 managed to put a roof over a large portion of what was then Atlanta’s red-light district, known for its bootleg whiskey, gambling, and numerous houses of prostitution along Collins Street where it intersected Decatur Street below. Prostitution in Atlanta, which existed in this area from around 1870 until 1910, has been well documented by sociologist-librarian Mandy Swygart-Hobaugh in her digital scholarship project Historic Harlots of Old Atlanta.4

In 1927, the “Empress of the Blues” Bessie Smith, who performed frequently in Atlanta, would record “Preachin’ the Blues” for Columbia Records. On it, the singer evokes past scenes from beneath the Washington Street Viaduct, where it would not have been uncommon to see “one ol’ sister by the name of Sister Green” drinking corn and shimmying like you’ve never seen!