The Urban Platform Campus

In the 1960s, a growing Georgia State College, now University, aspires to rise above downtown city streets

Fascination with the elevated city continued through much of the 20th century. By mid-century, with no more streetcars to contend with, upward movement in the city shifted almost entirely to accommodating the automobile — and in some cases, as we will see, removing pedestrians from the flow of car traffic below.

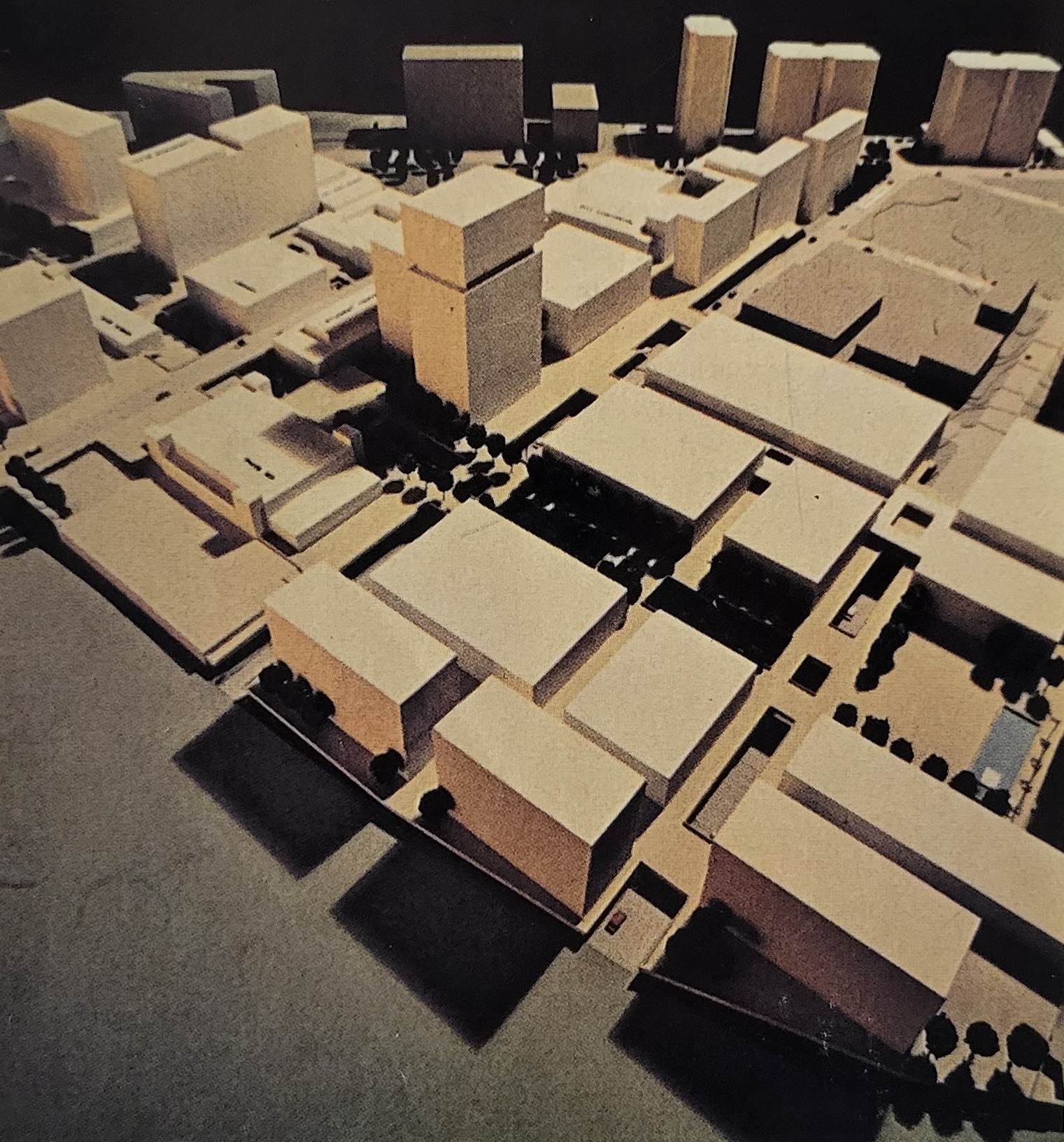

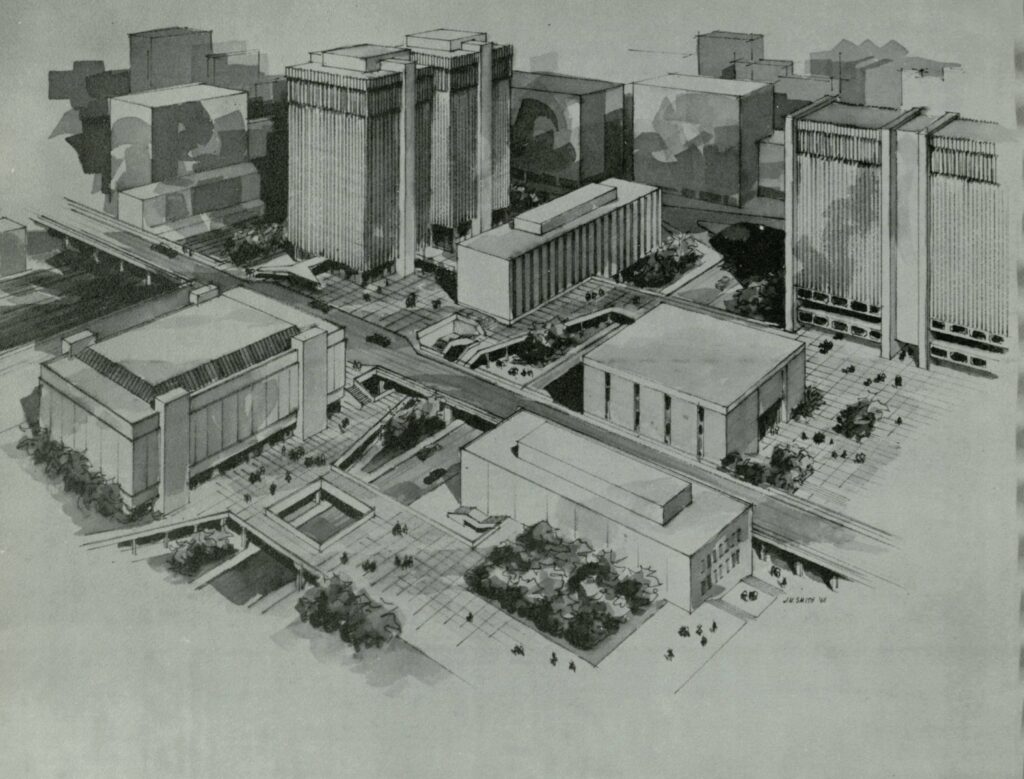

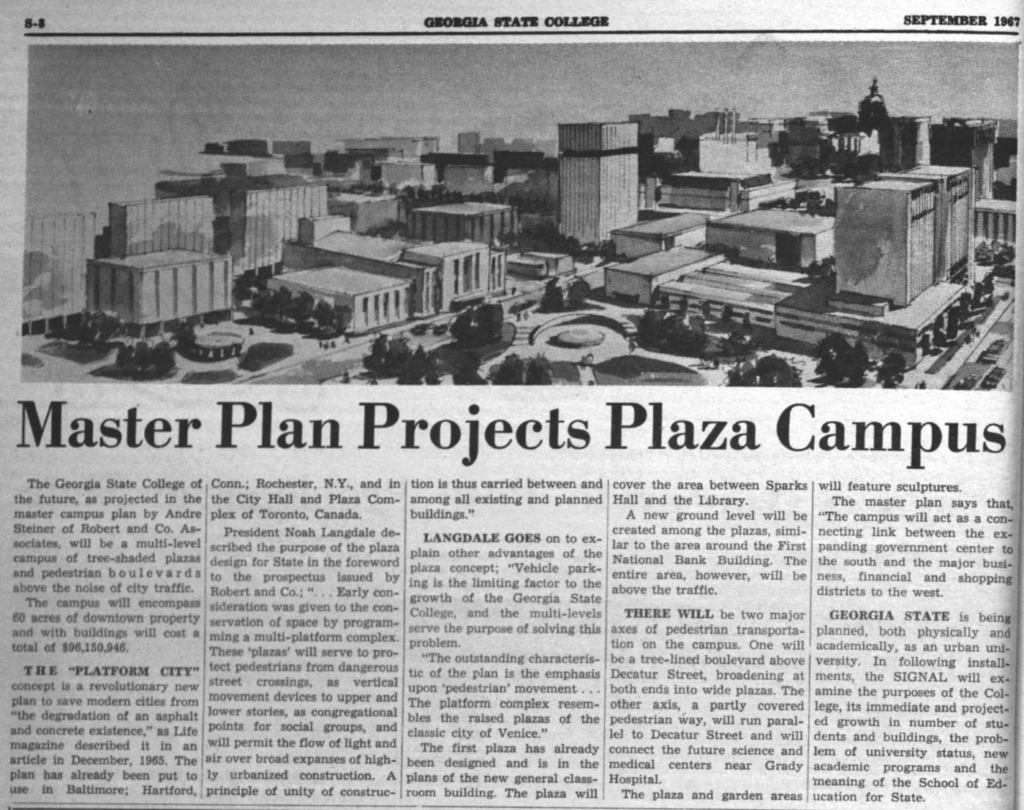

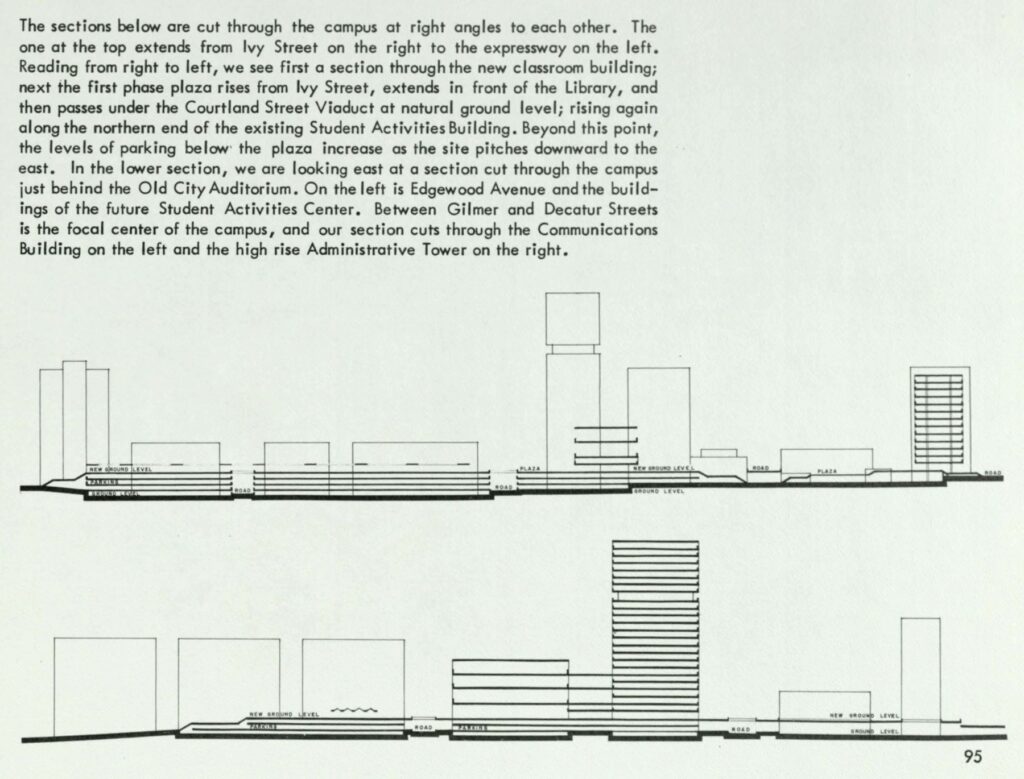

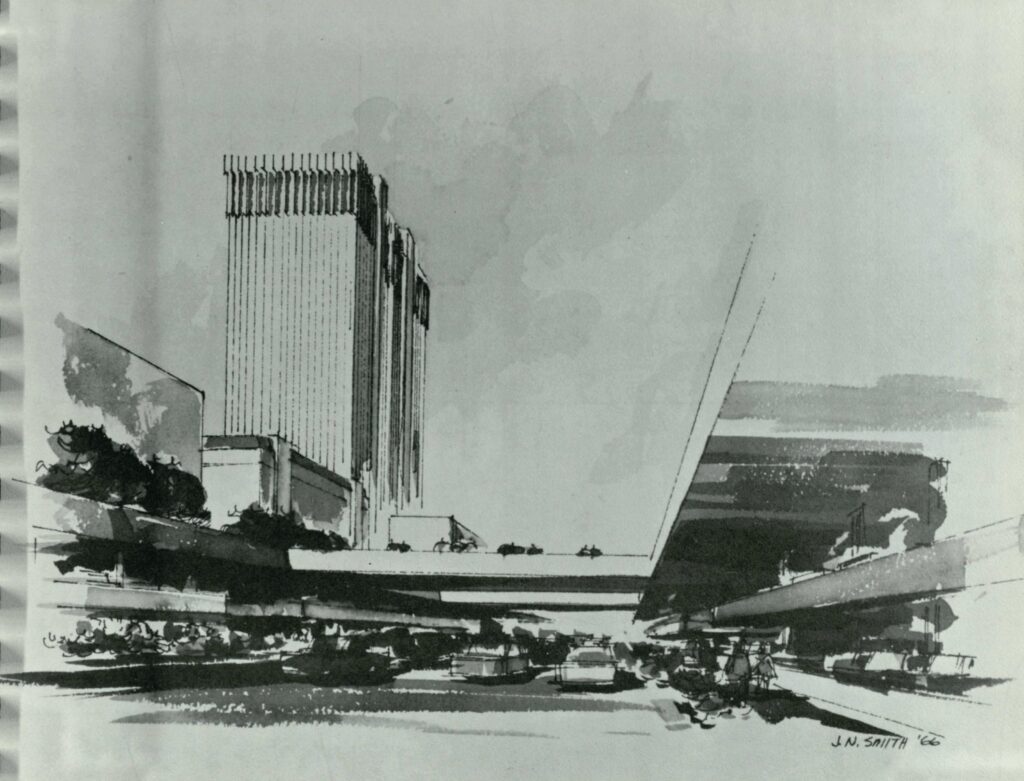

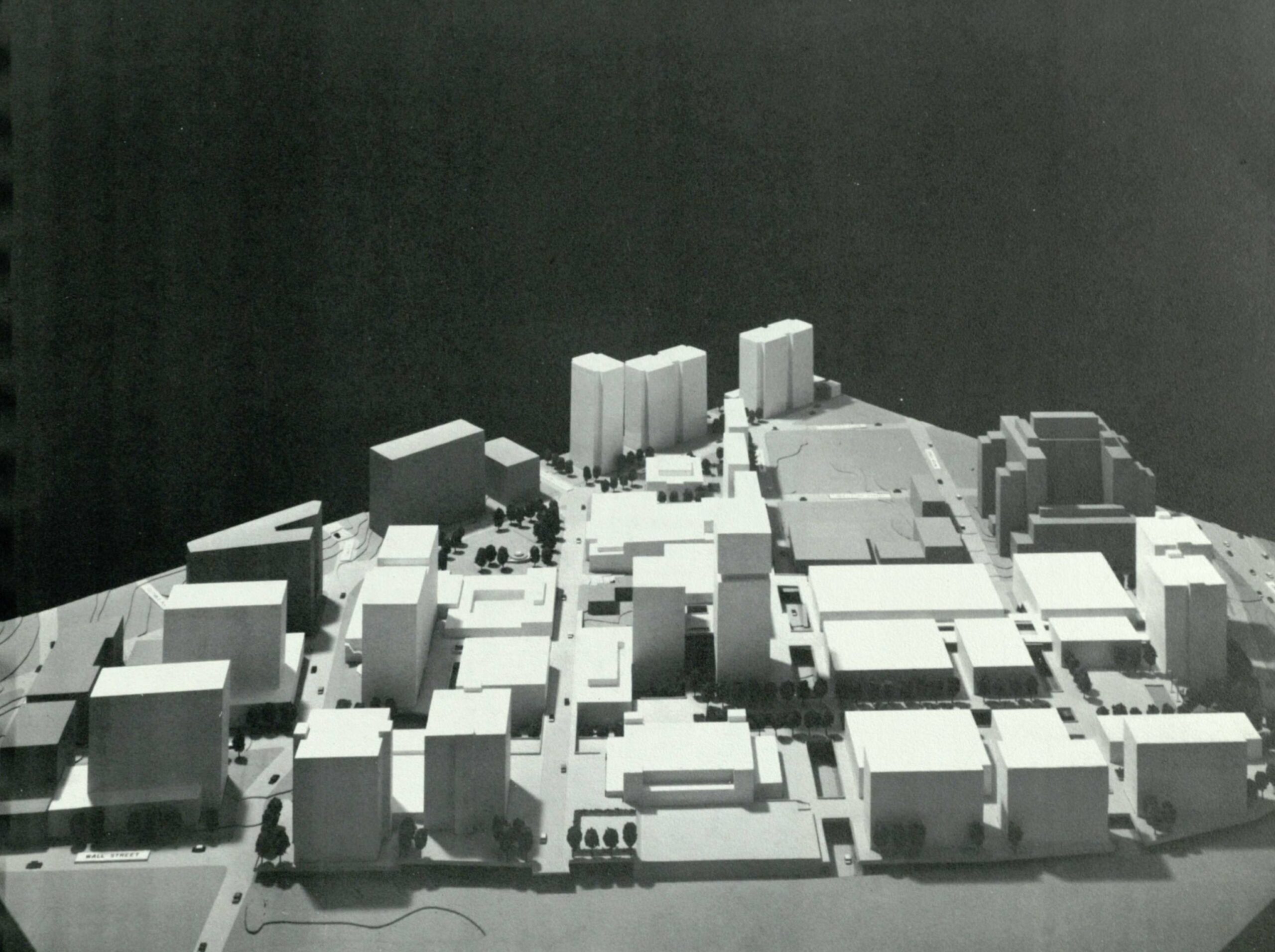

In the 1960s, plans were underway to develop a modern university for downtown. A growing Georgia State University (then Georgia State College), taking shape next to the viaducts, would feature elevated pedestrian platforms crisscrossing its urban landscape. In his visionary master plan for the Georgia State campus in 1966, Atlanta architect Andrew (André) Steiner (1908-2009), who taught urban design at GSU and was associated with the architectural firm Robert and Company Associates, envisioned a sixty-acre “multi-level campus of tree-shaded plazas and pedestrian boulevards above the noise of city traffic.”1

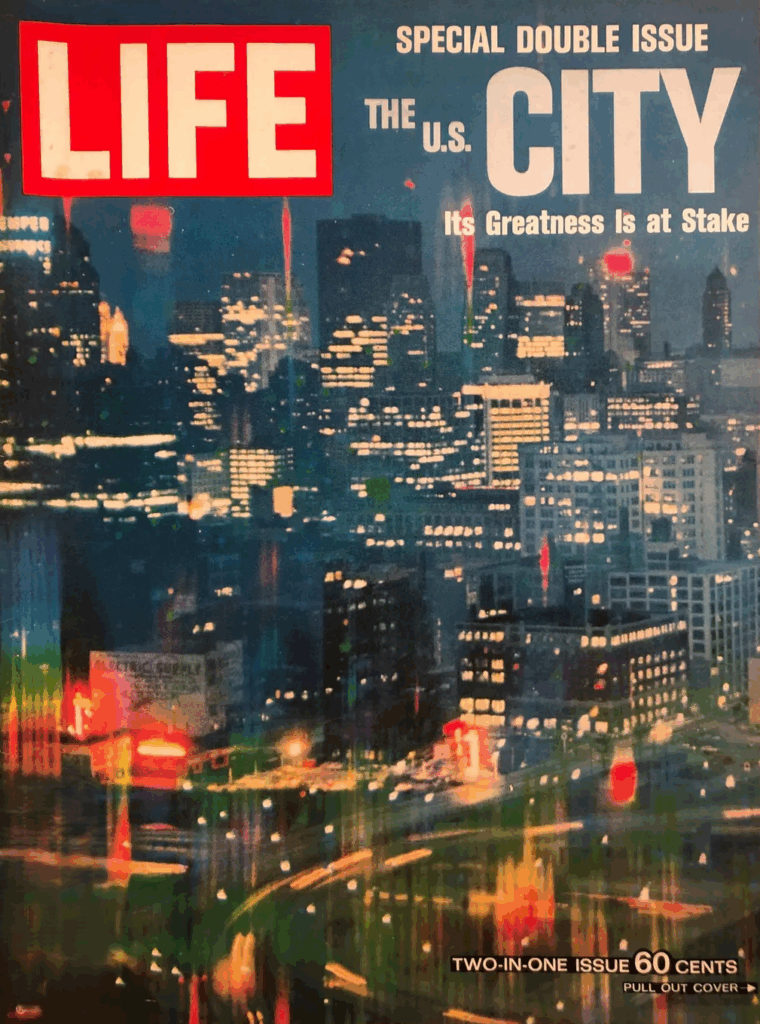

A year earlier, the “Platform City,” or city above the streets concept, had been hailed as “What’s to Come” in a special issue of LIFE magazine devoted to the future of cities. Appearing on its pages in 1965:

In the Platform City, the apparent “ground level” of whole towns – and in larger cities the central business districts, at very least – would be given over entirely to green landscapes and to uncluttered sidewalks. All or most buildings would be erected on stilts; all or most streets would be tucked “underground” in cavernous areas beneath the gardened platform.

The Platform City thus represents the first realistic challenge to the encroachment of the automobile on our civilization. Autos could be shunted into the underground parking areas, their drivers traveling by escalator or ramp onto the beautiful plateau which stretches through the city[ ]….“2

In 1967, in its student newspaper, The Signal, Georgia State’s President Noah Langdale heralded the “plaza campus” to come. The emphasis would be on pedestrian movement above the streets, serving to “protect pedestrians from dangerous street crossings,” providing “vertical movement devices to upper and lower stories” and permitting the “flow of light and air over broad expanses of highly urbanized construction.” Langdale went as far to say, “The platform complex resembles the raised plazas of the classic city of Venice” with garden areas and sculptures and cross-over bridges similar to those of the “Queen City of the Adriatic.”3

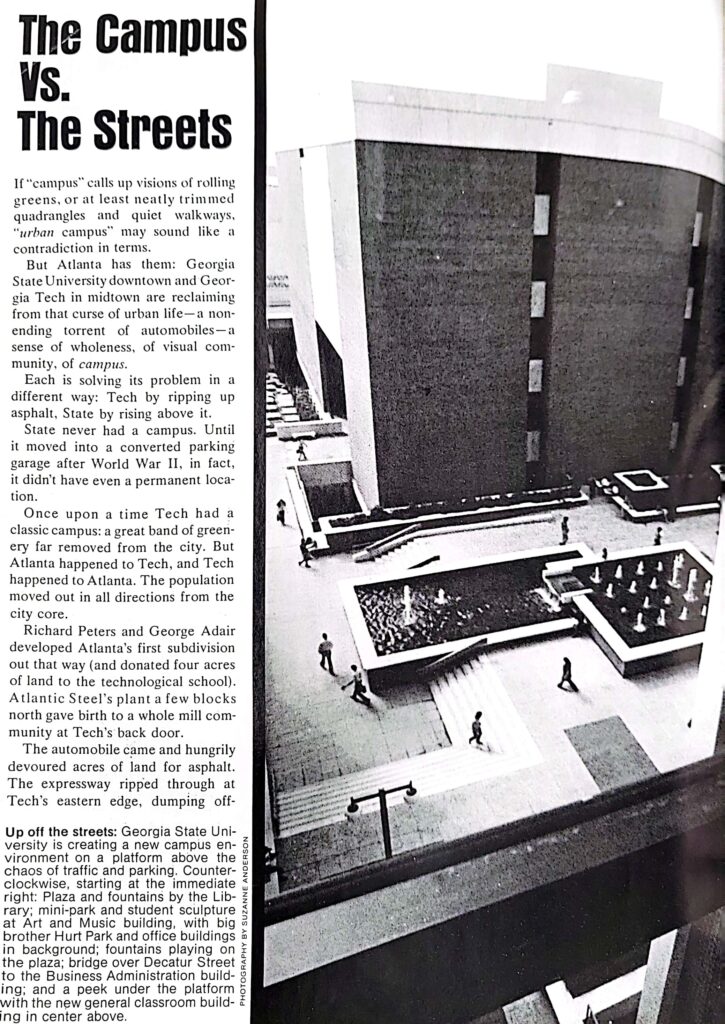

In 1972, an aptly titled article appearing in Atlanta magazine, “The Campus Vs. The Streets,” described the elevated vision for the new campus:

Taking a cue from its neighborhood – the portion of the central city that rose on viaducts above the railroad tracks – State adopted a “platform city” solution. And it added one vital improvement: It refused to allow cars “upstairs.” By bridging busy streets, State is creating pedestrian malls adorned by benches, greenery, and flowing water.4

Campus Growth and Urban Renewal

While these plans may have been forward thinking and visionary, urban policy researcher and GSU professor emeritus Harvey Newman has noted that Georgia State’s plans were also aligned with, if not partially driven by, urban renewal efforts in downtown Atlanta by city leaders.

The area around Georgia State was generally thought of as being in decline, and Decatur Street running through the heart of the new campus had long had an “unsavory reputation,” Newman writes. The street included a mix of Black-owned businesses other establishments “unpopular with upper status [B]lacks and whites.”5

As reported in the Georgia State Master Plan in 1966, the Atlanta Housing Authority described areas around the campus at the time as:

… badly blighted, containing long obsolete, dilapidated, poorly maintained commercial establishments, which, because of their close proximity to the central core, involved high acquisition cost. Twenty-five percent of the buildings were vacant. An unusually high incidence of crime and social ills were traceable to the area. During a portion of 1960 and all of 1961 Atlanta Police records revealed the commission of 188 crimes in the area, including 49 burglaries, robbery, larceny of 29 autos, 102 other larcenies, and 7 aggravated assaults. The economic loss of this area to the city, the continued decline of the area, the social defects and their costs in public funds indicated an area ripe for renewal.6