A Campus Transforms

As Georgia State University solidified its place in the urban landscape, campus leaders struggled for decades to decide what to do with Kell Hall, due to its unconventional layout and many quirks. Eventually, by 2019, plans were in place to demolish it to make room for street-level green space.

Making it Work at Georgia State

Georgia State has been talking about destroying Kell Hall for 50 years, almost as long as it’s owned it.

Spencer Roberts, Digital Scholarship Librarian, Georgia State University, 2019

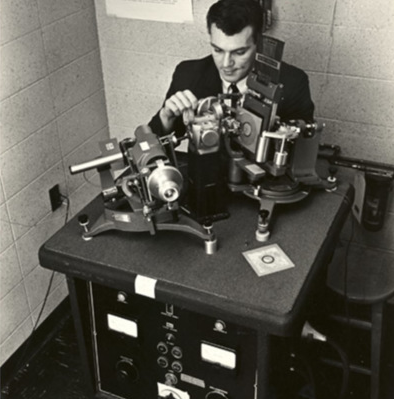

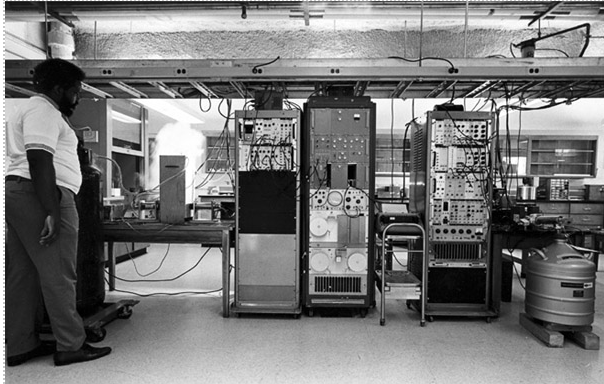

We persevered considerably. It was inefficient and unattractive to say the least, but there was incredible gut-level commitment and can-do. A lot of good science got done in fairly primitive conditions. We were pretty productive in spite of Kell Hall. It’s a measure of how dedicated faculty and students were that we walked into Kell Hall every day and did our work. We put up with all this.

W. Crawford Elliott, Associate Professor of Geosciences, Georgia State University, 2019

When I interviewed here for a position in chemistry in 1965, the provost told me I could expect to move out of Kell Hall in three years. Approximately every 10 years thereafter, there was the story: “Oh, we’re going to be moving out of Kell Hall into here or there.” Come 2018, we finally moved out of Kell Hall.

David Boykin, Professor Emeritus of Chemistry, Georgia State University, 2019

From the day I arrived on campus, I thought Kell Hall was antiquated and really should be torn down.

Carl Patton, GSU President (1992-2008)

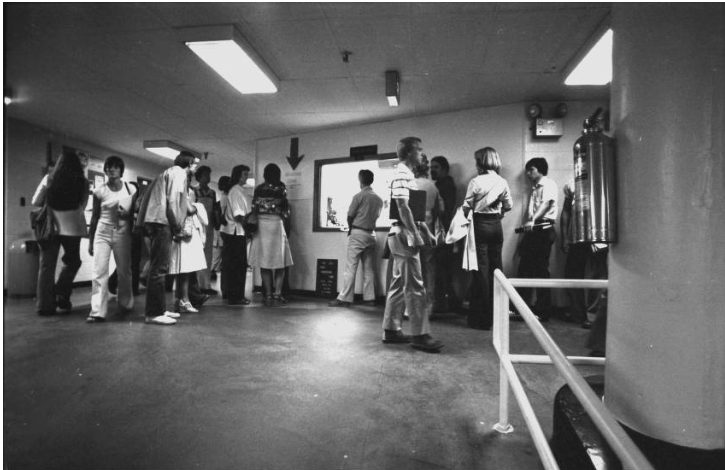

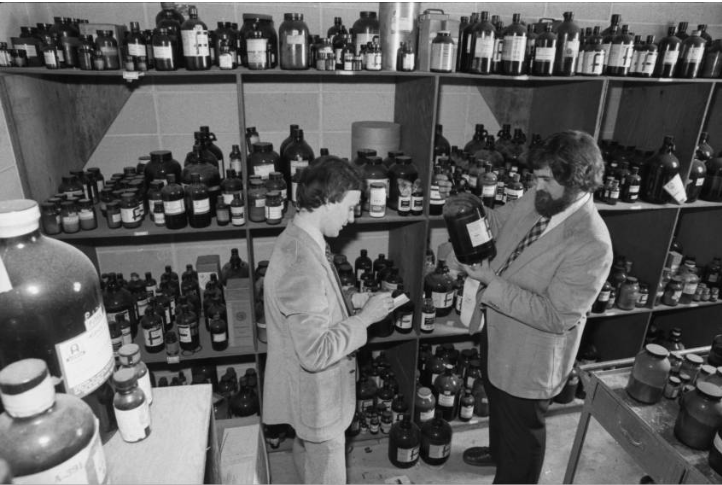

The expansion of scientific research and education at Georgia State was central to its transformation into a world-class urban university. Nevertheless, the inadequate facilities for science on campus at Kell Hall were a source of tension since 1969.1

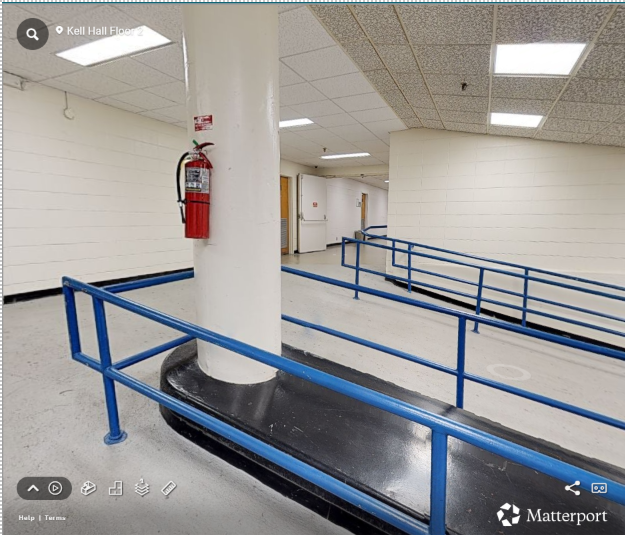

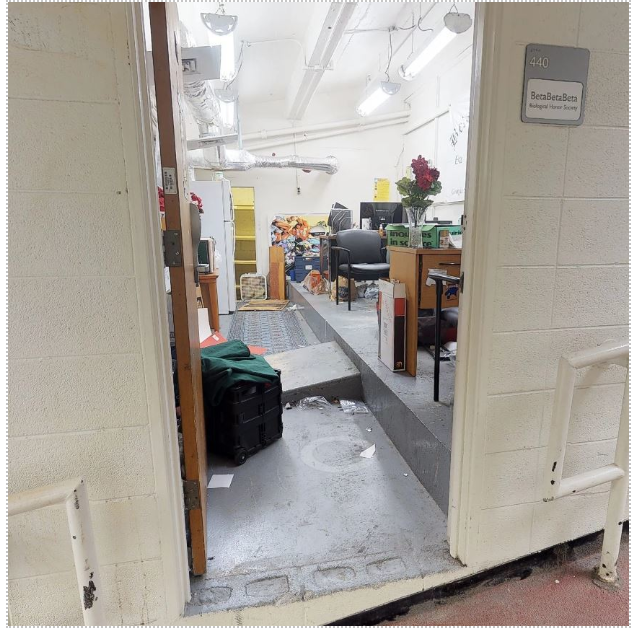

During the 1970s, as the university built new facilities and connected them with elevated platforms, students and faculty made do with physics and chemistry labs, anthropology collections spaces, and biology facilities in the crowded warren of interconnected spaces in Kell Hall. Every time they were invited to do so, the faculty complained about the facilities.

A series of memoranda from 1979-1980 offers a case in point:2

We have reason to believe that a building which will include the sciences may be a possibility toward the end of the next decade. If there is any reason for hope about a new building or additional space, our departments would rather make only the essential modifications of Kell Hal and put up with it for another ten years than go through the disorders associated with total renovation. Should there be a new building to move to, could not Kell Hall be remodeled as a nonscience building for significantly less than its renovation as a science facility will cost?

College of Arts and Sciences Kell Hall Committee Memorandum to Dr. Eli A. Zubay, Vice President of Academic Affairs, November 12, 1979

The top priority continues to be the need for expansion space followed by improvements in the heating/ventilation/air conditions (HVAC) system, the plumbing system (including toilet facilities) and the electrical system. The Chemistry and Biology Departments state their number one needs in terms of safety improvements for fume hoods, animal facilities, chemical storage, and lab exits… However the committee expressed concerns about the University’s ability to make effective decisions on such major renovations matters in the absence of an academic program for the use of Kell Hall.

Joe B. Ezell, Assistant Vice President for Institutional Planning, Analysis of Kell Hall Renovation Recommendation, Memorandum to Dr. Eli A. Zubay, December 20, 1979.

In view of programmed needs and even considering relocating non-academic functions, this Committee soon realized it was facing a significant reduction in usable space for the sciences in Kell Hall. This resulted in large measure from applying current code standards during renovation to a building which could not be physically expanded. Worst of all, there was no way to prevent a 5-7 year period of chaos during which major construction activities intermingled with academic and research programs which would have to continue in Kell Hall. Such conditions would severely curtail our thrust in these areas, if not endanger the survival of these programs… Currently there exists a genuine concern both in the Board of Regents and the General Assembly to correct the conditions in Kell Hall—the momentum thus gained must not be lost.

Kell Hall Committee, 1980

Ultimately, a new Natural Science Center would open in 1992, the first year of President Carl Patton’s tenure. Biology and chemistry would finally have a new home, but a motley crew of offices and classrooms would still remain in Kell Hall.

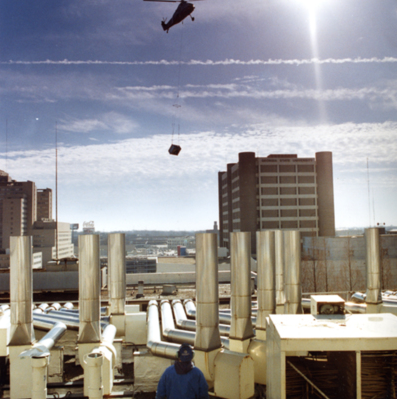

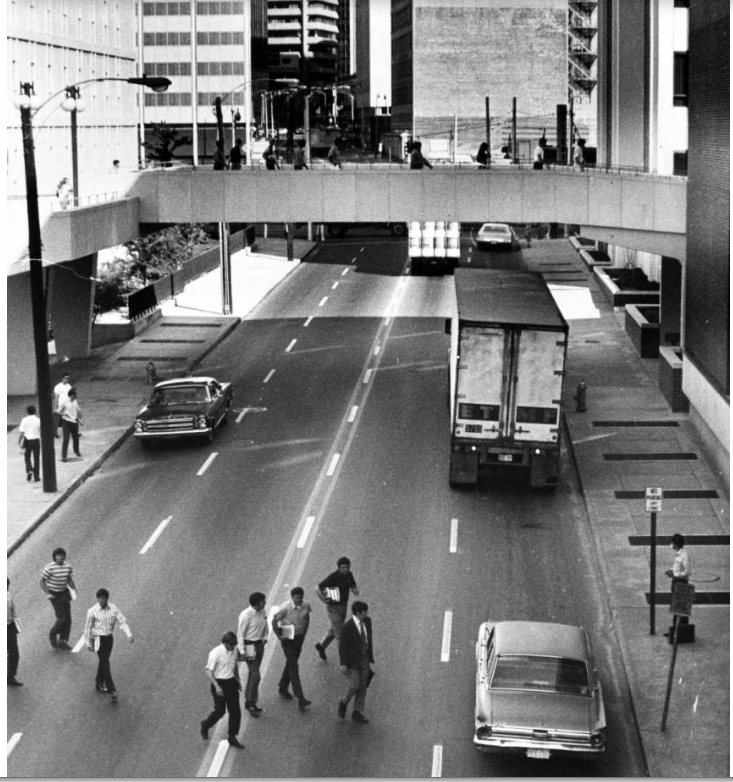

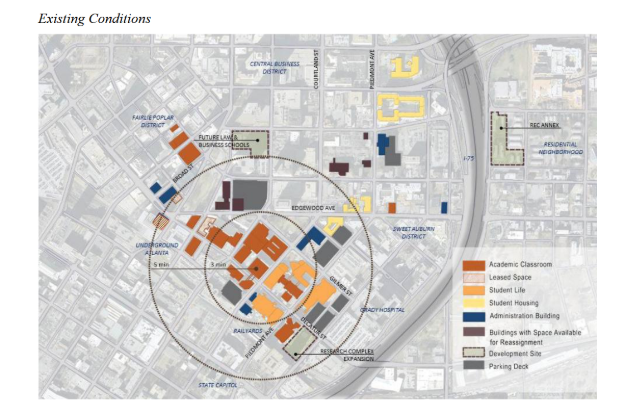

Between 1970 and 2000, Georgia State had grown to become a combination between what the American Institute of Architects Guide to Atlanta had hailed as a “platform campus” in 1974 (with the opening of a plaza spanning Decatur Street between what was then the Business Administration Building (now Classroom South) and a new Arts and Sciences building (now Langdale Hall)) and a growing portfolio of annexed and repurposed buildings stretching from the Fairlie Poplar district to Auburn Avenue.

The Architects Guide in 1975 heralded what GSU had managed to accomplish in such a short period of time:

Georgia State is a school of bold architecture; sixteen buildings, rising higher and higher, linked together with spans and landscaped plaza. Its growth has been phenomenal. Eighty percent of its classrooms have been constructed since 1968. Student enrollment has increased almost 500 percent in the last ten years and is expected to reach 22,000 in 1975. The students are unique. Dedicated and intense, approximately 80 percent of those attending class also work. And the campus may be like no other you’ve ever seen.

The Architects Guide, 19753

However, by the middle of the first decade of the 21st century, as Georgia State was anticipating its centennial, the “platform campus” model, which had removed pedestrians from the street level and the possibilities of natural areas and green-ways, was beginning to lose its appeal in the eyes of the students and leadership alike. Carl Patton had overseen the university’s acquisition of facilities associated with the 1996 Olympics, including its first dormitories, and residential students were beginning to demand more greenspace. Mark Becker, who became president in 2009, envisioned an urban oasis, a campus that would reconnect with the ground.

De-platforming GSU

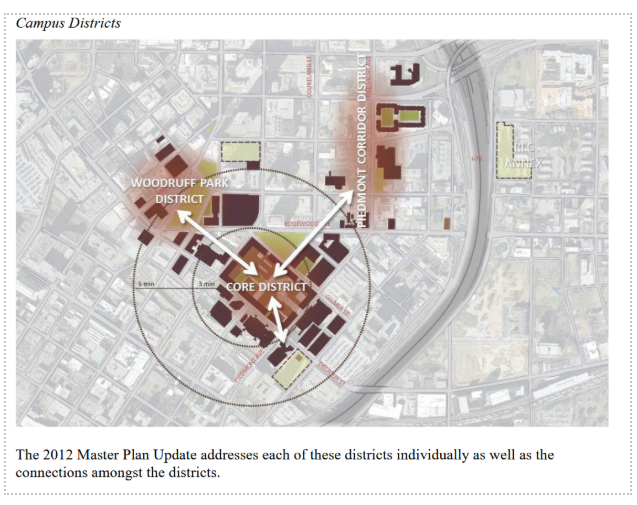

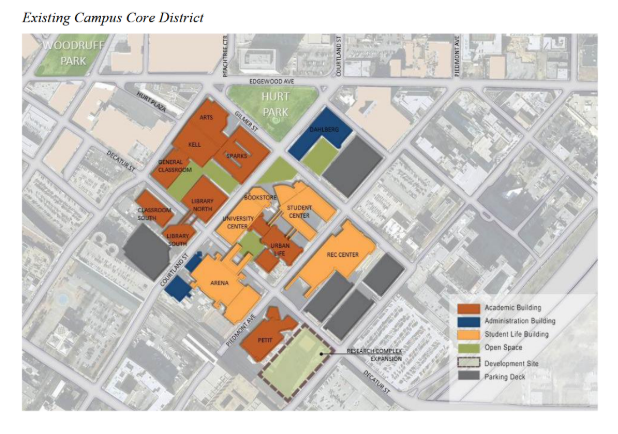

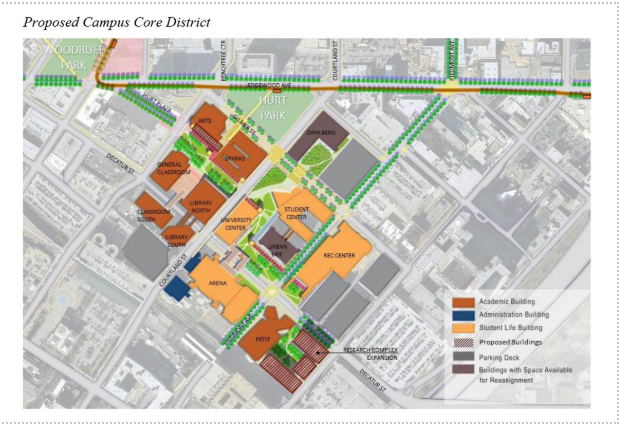

Preparing for the university’s 100th anniversary in 2013, a master plan was developed in 2012 which envisioned the demolition of Kell Hall to make way for a new greenway in front of Library North. Future connections to Hurt Park and Woodruff Park were also envisioned, along with a northward and eastward expansion with new facilities for law, business, and student residences.

Within the proposed greenway, the plan introduces a series of vertical structures containing elevators and stairs as a means of providing new and improved pedestrian access into the adjoining building facilities and as a place making element for the campus. With the removal of Kell Hall, the configuration of the adjoining Arts & Humanities building will permit the addition of a tier of new laboratories for the arts needed to accommodate the existing and future programs. The proposed greenway will provide Georgia State its first landscaped quadrangles serving as safe and attractive pedestrian connections between campus buildings in the core and the much-sought outdoor landscaped communal study and social spaces.

Georgia State University Master Plan Update, 20124

A Preservation Plan commissioned for the university’s centennial in 2013 honored Kell Hall’s legacy while addressing its likely demolition. In short, it declared that “Kell Hall does not retain its historic integrity due to multiple alterations” and recommended that it not be considered eligible for historic preservation.5

In a 2017 article in Creative Loafing, Adjoa Danso wrote:

In 2013, the University unveiled its most recent master plan, a blueprint for GSU’s long-term footprint on Downtown Atlanta. The idea is to create precincts within the university’s sprawling campus: Academic spaces cluster around the east side of Woodruff Park; classrooms, libraries and student services make up the university’s core on either side of Courtland Street; student housing stretches along the Piedmont corridor; and scientific research infrastructure resides on the southern end of Piedmont Avenue. The biggest and most time-consuming undertaking is the demolition of Kell Hall, a classroom building created out of a 1920 parking deck, complete with ramps in lieu of stairs, replacing it with a greenway and new arts building.

Adjoa Danso, Creative Loafing, 20176

In 2018, with plans underway for Kell Hall’s demolition, a historic structure report was commissioned by Georgia State University and produced by Lord Aeck Sargent Responsive design. The report was produced to comply with the “Georgia Board of Regents Due Diligence guidelines for the proposed demolition of Significant Resources.”

The report concludes that while the historic significance and potential National Register of Historic Places eligibility of Kell Hall has been recognized, Georgia State University has long planned for its demolition. Campus planning documents going back at least 20 years identify Kell Hall for demolition and planning for the greenspace that will replace the building is significantly developed.

Historic Structure Report, 20187

To prepare for the building’s demolition, the Georgia State University Library and the Student Innovation Fellowship Program partnered to produce a website to digitally preserve “the histories, aesthetics, and experiences of Kell Hall to commemorate its place in the history of Georgia State University.”

The resulting 3D capture of the building and series of 360 panoramas explorable through a Matterport interface have been archived by the Georgia State University Archives digital archives team and remain available through this website.

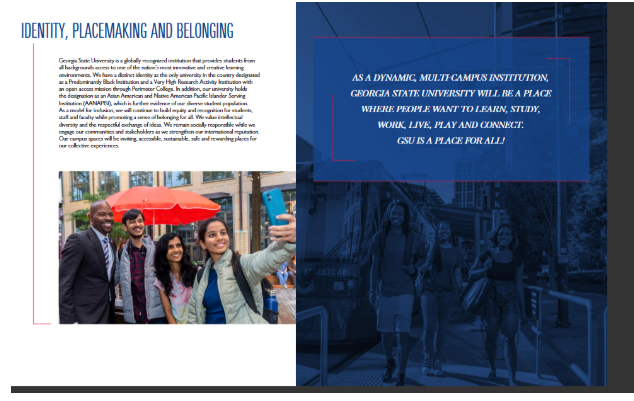

Placemaking for an Urban Campus

Kell Hall’s demolition began in 2019. By 2021, the area where it had once stood had been transformed into a new campus Greenway, connecting the campus east to west from the Student Center to newer campus buildings to the west, including the 25 and 55 Park Place towers and Aderhold Learning Center. In 2021, M. Brian Blake became the University’s 8th president. He soon brought on Jared Abramson as Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer in 2022. Abramson was responsible for launching a “placemaking” initiative to help students, faculty, staff, and visitors better navigate and feel part of the campus.

The “GSU Blueline Project” was officially underway by 2024.8 In a campus memorandum recognizing GSU’s being honored by the American Marketing Association for its “Visual Branding and Identity” Jared Abramson said:

Visual branding and campus improvement are guided by our Strategic Plan: BluePrint to 2033 and the pillar of Identity, Placemaking and Belonging. Georgia State University is committed to providing the best possible campus experience for its students, faculty and staff in its unique downtown Atlanta and Perimeter College locations. Initiatives including the GSU Blue Line, Panther Places, Panther Ride, College Town Downtown and more are part of the ongoing effort to constantly improve the day-to-day environment for one of the most successful and dynamic universities in the nation.9,10