A Very Atlanta Idea

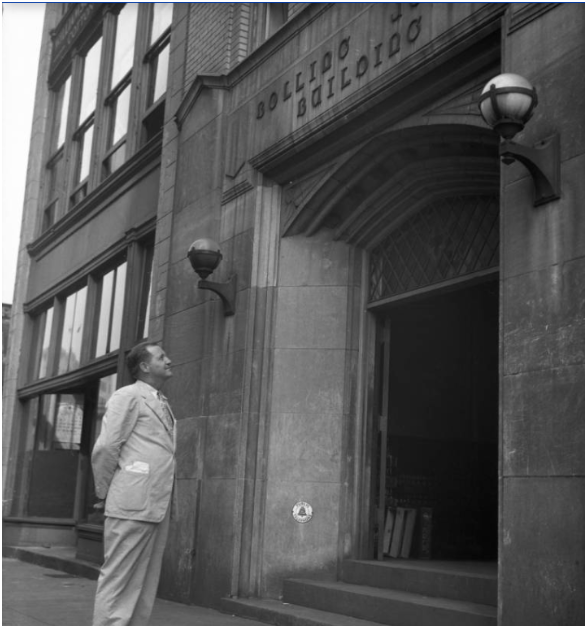

Originally known as the Bolling Jones Building, or the Ivy Street Garage, Kell Hall started its life as Atlanta’s first modern parking garage, an “automobile hotel” in use from 1925 – 1945. Out of scrappy ingenuity, it would be transformed into GSU’s first permanent building.

Meeting the Needs of a City on the Rise

The new South is enamored of her new work. Her soul is stirred with the breath of a new life. The light of a grander day is falling fair on her face. She is thrilling with the consciousness of growing power and prosperity.

Henry Grady, speech given to the New England Society in New York City on December 21, 1886

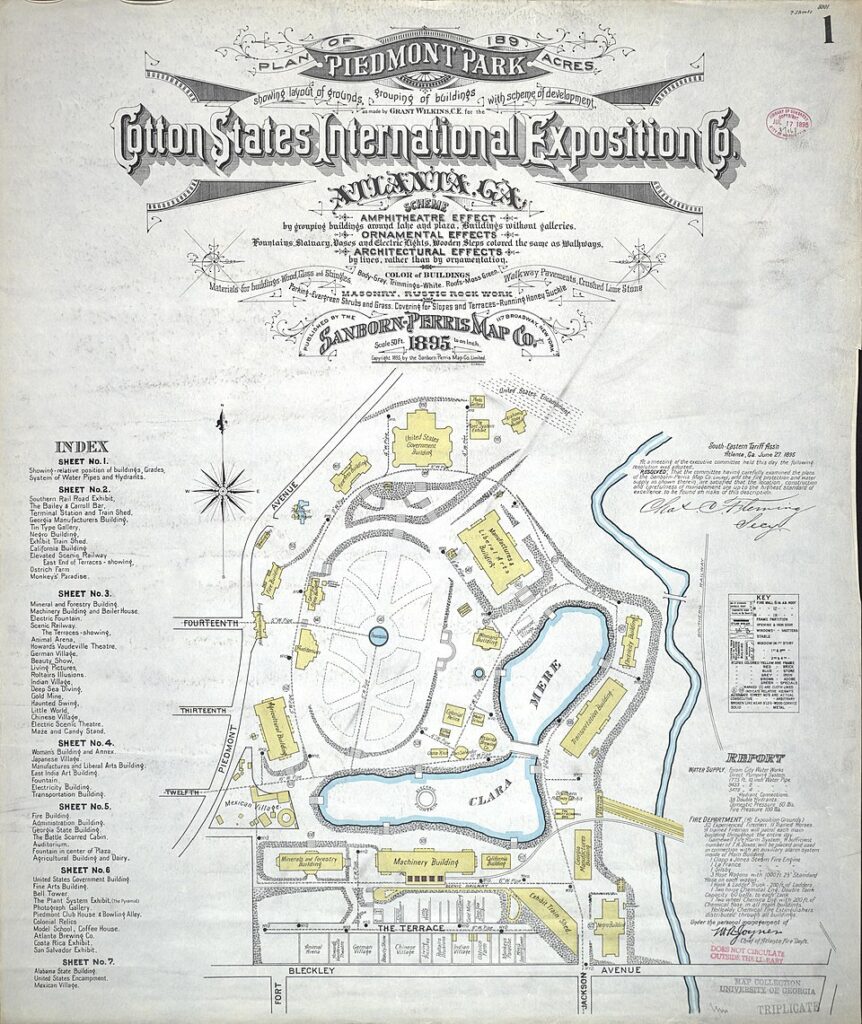

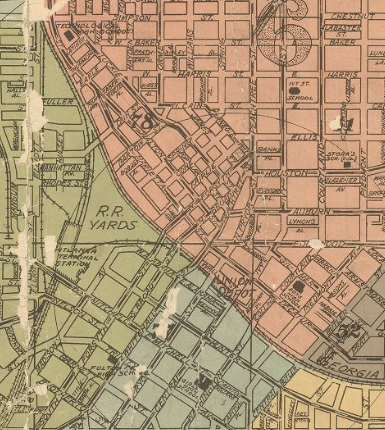

By the turn of the 20th century, Atlanta was a growing city, self-declared capital of the “New South.” In 1895, electric trolley cars transported visitors from Atlanta’s passenger depot — where they could arrive by any of the four major rail lines that served the city—to the Cotton States and International Exposition. There, they could view displays of modern machinery and appliances. The deafening hum of motors large and small signaled technological changes that would soon sweep through the city.

Still, by 1913, when the Georgia School of Technology began offering an Evening School of Commerce in three rooms of its Lyman Hall Chemistry Building, less than 1% of Americans owned a car.1 Despite the populist rhetoric of tycoons like Henry Ford and Ransom Olds, automobiles remained in the purview of a wealthy minority until the post-World War II suburban explosion of the 1950s.2 At the same time, Atlanta’s elites would spend the 1920s investing political and economic capital in a campaign to transform Atlanta’s streets into spaces dominated by automobiles.3 Thus, the kind of luxury downtown parking garage that would eventually become Georgia State’s first permanent building made sense both economically and socially.

While car culture was still nascent, education was increasingly being viewed as a necessity for advancement. In 1914, the year that the Evening School of Commerce moved its classes into the Walton Building in downtown Atlanta’s Fairlie-Poplar district, a cluster of schools were growing to serve the diverse population in and around what had already become Georgia’s largest city.4 Atlanta’s historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) traced their roots to the end of the Civil War when Atlanta University was founded as a graduate and professional school in 1865, quickly joined by Clark College in 1869. Morris Brown and Spelman Colleges would join the archipelago in 1881, followed by Morehouse in 1913. Agnes Scott, a college for White women, had been established in nearby Decatur since 1889. In addition to Georgia Tech, which was founded in 1895, White men could attend Emory University, which moved to Atlanta from Oxford, Georgia in 1914.5

Catering to the needs of working professionals, the Evening School of Commerce specialized in business courses taught at convenient times, in a location easily accessible from the boarding houses and rental properties inhabited by young people seeking to improve their fortunes.

L. M. Drummond, author of the Georgia State Historic Preservation Plan in 2014,6 characterized the early days of the campus thus:

The evening school’s non-traditional students, known then as ‘irregulars,’ were typically older, had full-time day jobs, and had established living quarters. These characteristics to a large extent determined the distinct physical plant of the urban college, where dormitories were not obligatory, as well as atypical administrative needs.

L. M. Drummond, Georgia State Historic Preservation Plan

An “atypical administrator” catering to “irregular” students, Dean Wayne Sailley Kell led the school during the first year of the U.S. involvement in World War I. He saw the declining enrollment of young men drafted to serve in the military as an opportunity to admit women, creating a unique loophole whereby 35 women received Bachelor of Commercial Science degrees from what was otherwise an all-male institution (Georgia Tech) between 1914 and 1933.

An “Automobile Hotel” for Ivy Street

While the first Georgia School of Technology Evening School of Commerce students were taking classes in a succession of buildings around downtown, from Walton Street to Auburn Avenue, another fledgling business was just starting to get off the ground.

In 1924, Bolling Jones, Jr., who had made his fortune presiding over the Atlanta Stove Works,7 became president of the Ivy Street Corporation, a development company determined to capitalize on a growing demand for parking it Atlanta’s increasingly high-density downtown.

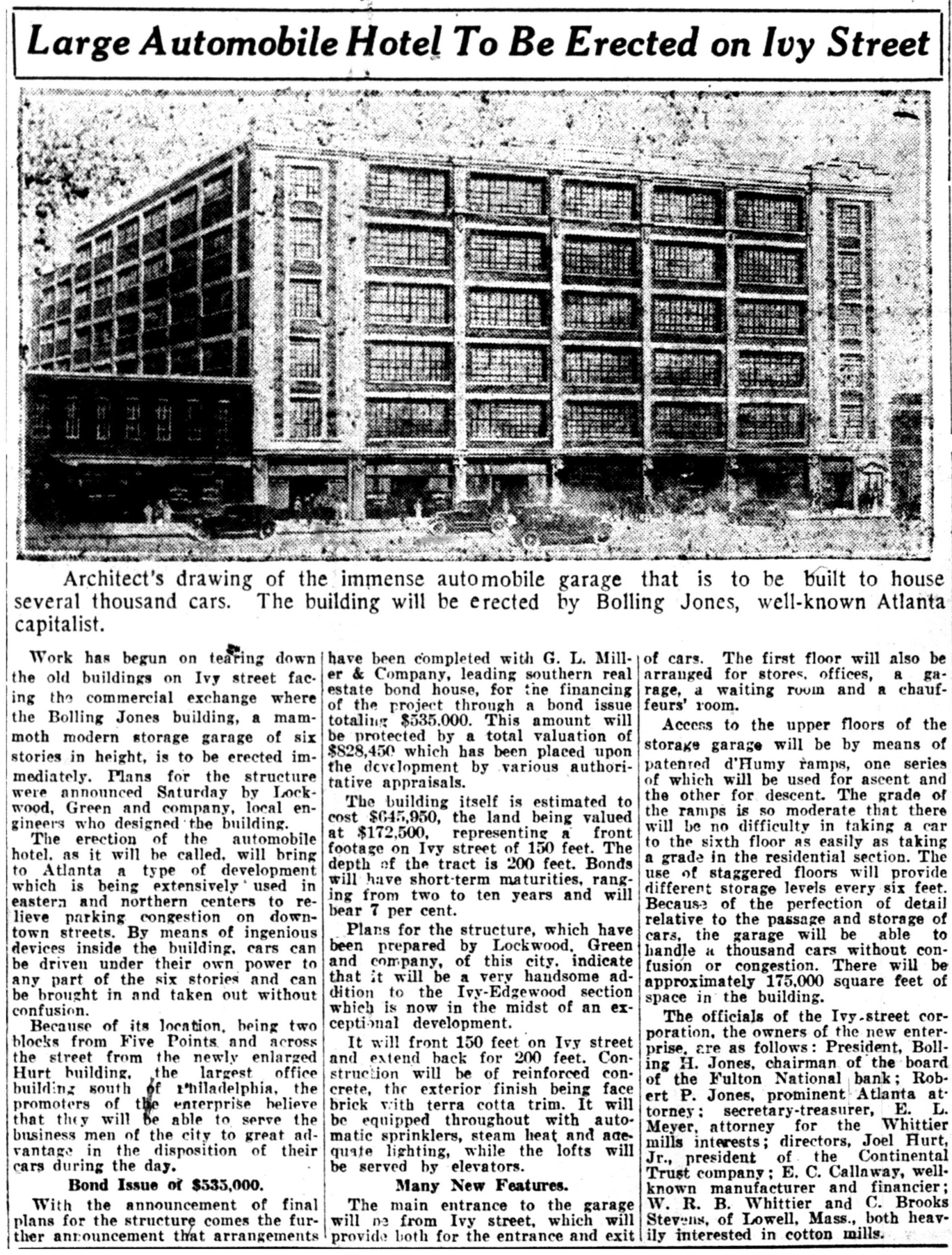

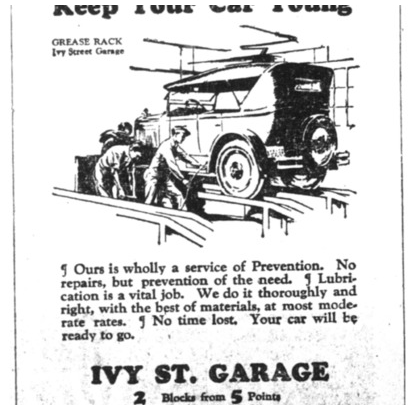

Fronting $828,450 for land and building costs, Jones and his partners worked with the architecture firm Lockwood, Greene, and Company to develop plans for a six-story “Automobile Hotel” which would provide space for up to 1000 cars. Accessible through a system of internal ramps, parked cars would enjoy steam heat and the protection of an automatic sprinkler system while their humans could access a waiting room, mechanical shop, chauffeurs’ lounge, stores, and offices on the first floor of the building.8

An Innovative Design

The d’Humy motoramp system offers unusual advantages in inter-floor transportation in multi story buildings, and may be applied to factories, warehouses and sales and service buildings.

Harold F. Blanchard writing in Engineering World, February 1921

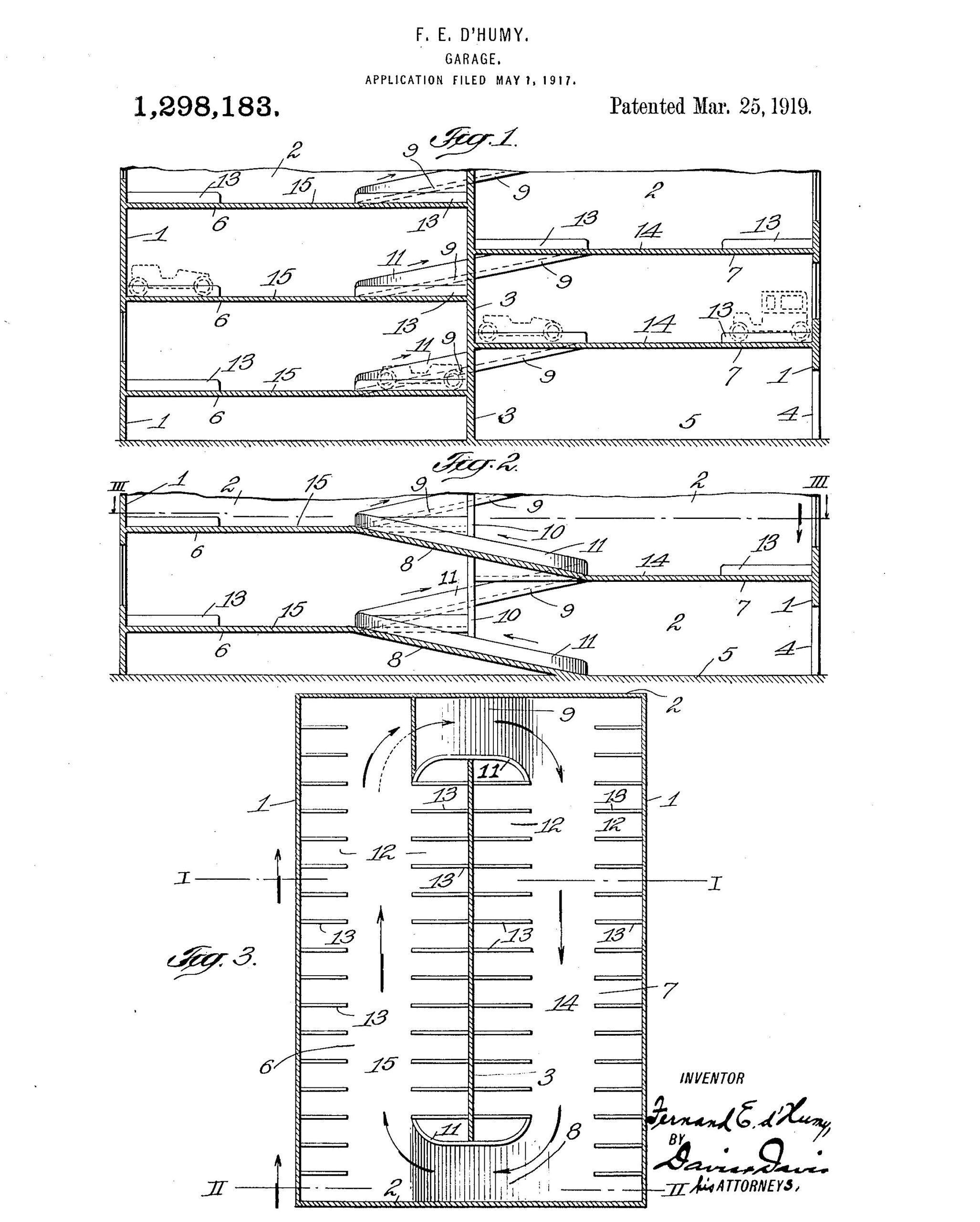

Application filed May 1, 1917. Serial No. 165,786, via Google Patents

Tasked by Bolling Jones and his associates with finding the best design for the Ivy Street location, the architectural firm of Lockwood, Greene, and Company selected the d’Humy Motoramp System which had been patented in 1919. The system featured staggered floors with short, shallow ramps between them. The d’Humy design was trumpeted in trade journals including a 1925 brochure called Building Garages for Profitable Operation which suggested that a seven-story garage could earn up to $141,450 per year in profits.9 This would recoup the original cost of development in less than a decade.

Building a Viable Business

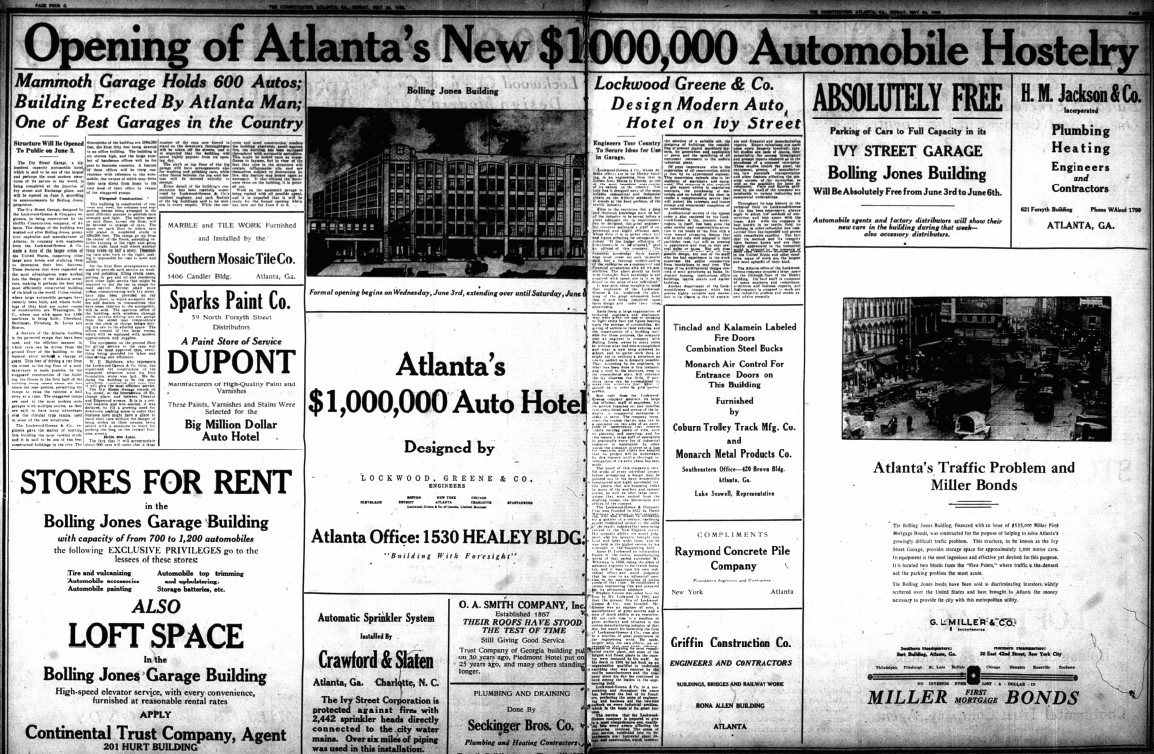

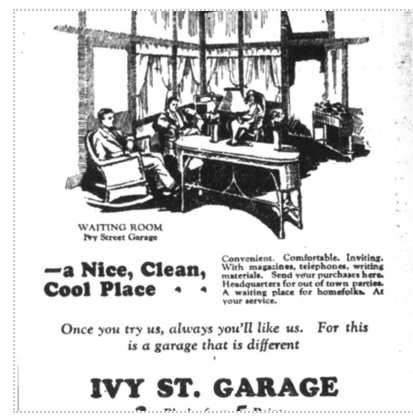

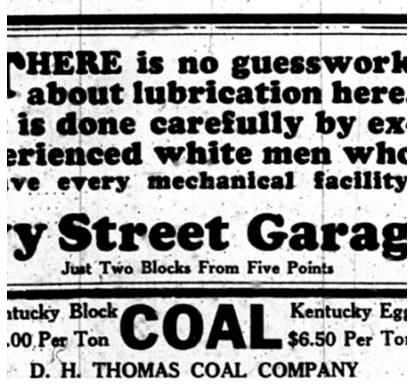

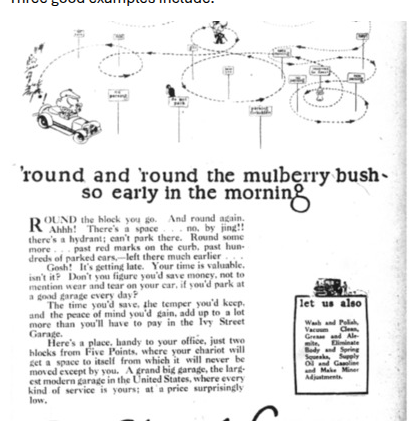

The Atlanta Constitution heralded the opening of the new Ivy Street garage in May 1925 with an article entitled “Opening of Atlanta’s New $1,000,000 Automobile Hostelry.” The article described the building as “perhaps the best and most efficiently constructed building of its kind in the world.” After the opening, which featured an automobile show with free parking for attendees, the Bolling Jones company placed ads for the garage in local newspapers and partnered with retailers to entice middle and upper-class customers to shop downtown, assuring them that their cars would be taken care of during their shopping excursions. Ads featured various rhetorical strategies including humorous anecdotes about the frustration of street parking, emphasizing safety, and appealing to the bigotry of their desired White clientele.

While Bolling Jones and his partners worked to market the new garage, and to find tenants for their first-floor stores and loft spaces on the upper floors, the Evening School of Commerce, now under the direction of Dean Frederick B. Wenn, was growing rapidly. Between 1914 and 1925, it had already occupied three different buildings. In 1928, George M. Sparks, who had become the school’s director the year before, purchased the first building for the school, moving it from its fourth to fifth location (at 161/223 Walton Street) in 1930. It would remain there for the next eight years.

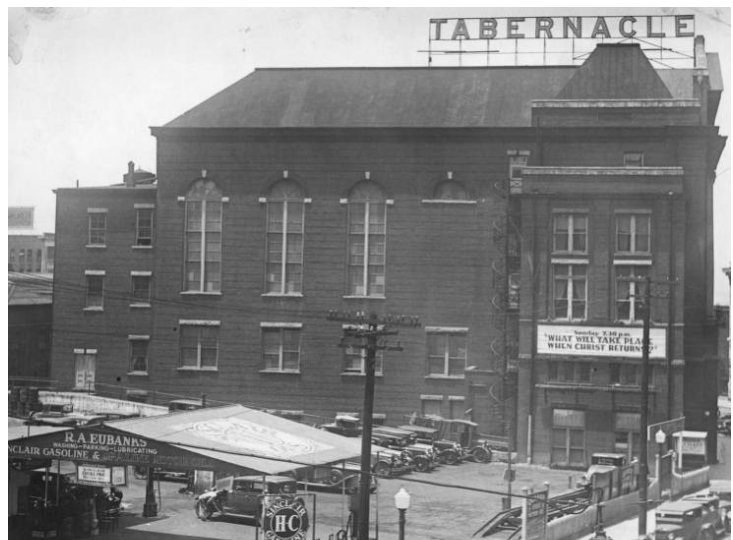

While some Georgia students weathered the early years of the Great Depression by taking evening commerce classes downtown, the state made a bold decision to reorganize higher education in 1931, establishing the Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia. The Regents made the decision to separate the Evening School of Commerce from Georgia Tech in 1933, naming it the University System of Georgia Evening School, and then renaming it the Atlanta Extension Center of the University System of Georgia (or Atlanta Center) in 1935. Despite the effects of the Depression and lobbying by Georgia Tech to prevent competition by limited course offerings, the Atlanta Center reached a record enrollment of 1748 in 1938, the year it moved into a new home purchased by Director Sparks on Luckie Street (the former Nassau Hotel and old Baptist Hospital, next door to want is now the Tabernacle Theater).

Director Sparks’ ambition and savvy for promoting the school despite economic and political challenges would ultimately lead its path to converge with the Bolling Jones building after World War II.

Making Way for Changing Times

World War II changed Georgia, and especially Atlanta, in profound ways. Atlanta’s municipal airport, located at Candler Field, doubled in size after it was declared an air base by the U.S. government in 1940. By 1942, it would be named the nation’s busiest with a daily record of over 1,700 takeoffs and landings.10 Northwest of the city, in Marietta, Bell Aircraft would open one of the country’s largest war manufacturing plants, building over 600 Boeing B-29 Superfortress airplanes and employing over 28,000 Georgians before its temporary closure in 1945. With troop transports making numerous stops at its Terminus station, Atlanta would solidify its reputation as a transportation and distribution hub, becoming a cultural crossroads for the Southeast and cementing its reputation as the capital of the New South at mid-century.

Despite bringing new opportunities for Georgians and strengthening various sectors of the economy, World War II disrupted everyday life in Atlanta. For the Ivy Street garage, this meant a loss of profitability. Under new management since 1939, the Bolling Jones company decided to put the building up for sale in 1945.

Meanwhile, although it was not a priority for state’s Board of Regents, which focused increased resources on the flagship University of Georgia in Athens, the Atlanta Center continued to grow in enrollment as returning veterans sought educational opportunities with funding from the G.I. Bill. Ever on the lookout for deals, Director Sparks pounced on the opportunity to purchase the Bolling Jones building. His thrifty decision would set the scene for public higher education in postwar Atlanta.

As the city set its sights on freeway construction, revolutionizing urban car culture, students would come to replace cars in its oldest parking garage, climbing their way toward new opportunities.

Bolling Jones Building in 3D

Created by GSU Library staff member Cory Schlotzhauer, this model of the Bolling Jones Building is based on photographs from the 1920s to the 1940s. The stores seen on the first floor are accurate to that period. The model was produced using Blender.