Make Way For State

After World War II, both Atlanta and its downtown college navigated a period of rapid growth amidst political and social challenges, leveraging Kell Hall and other resources to become independent from the University of Georgia in 1955, and paving the way to become Georgia State University by 1969.

Taking Root Downtown

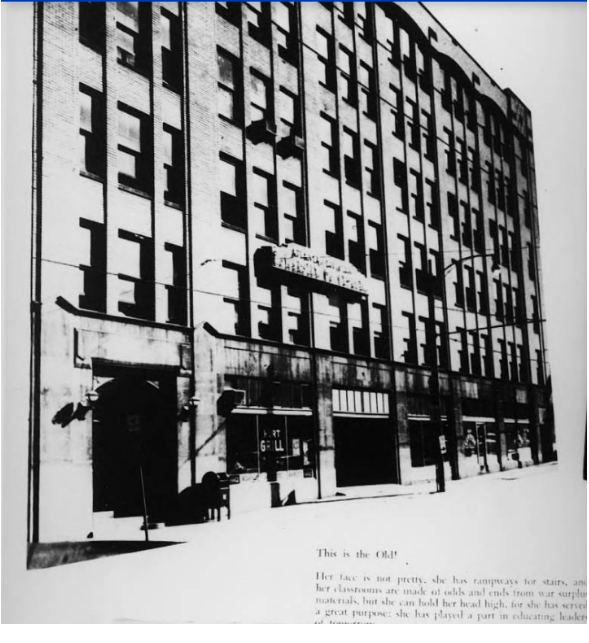

Leveraging funds made available through the 1944 Surplus Property Act, which freed up federal resources to convert buildings to educational facilities, Director George Sparks persuaded the Board of Regents to commit almost $300,000 toward renovating the Bolling Jones building for student use, far less than it had cost to build.1

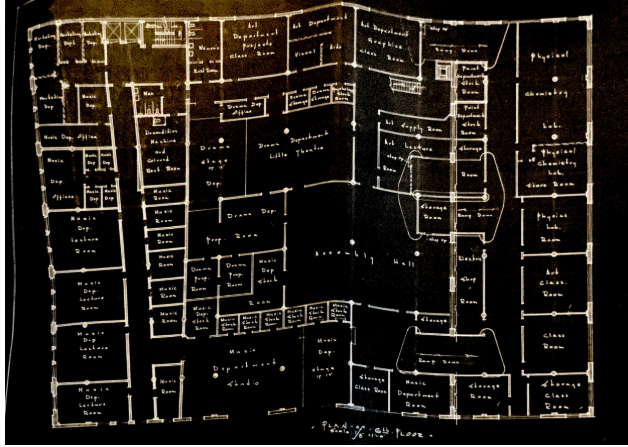

Construction materials were difficult to come by due to postwar shortages, but Sparks used his networking skills to procure materials from various decommissioned war matériel plants, ranging from Bell Bomber to Firestone Rubber, to Oak Ridge Labs in Tennessee.2 Rapid renovations, beginning with a $100,000 facelift in October 1945, enabled the school to hold its first classes in the Bolling Jones building in 1946. Twenty-five former offices were converted into 35 classrooms, and six laboratories were built for the biology, chemistry, and physics departments. The top floor was reserved for a theater space, with plans to use the roof for outdoor recreation.

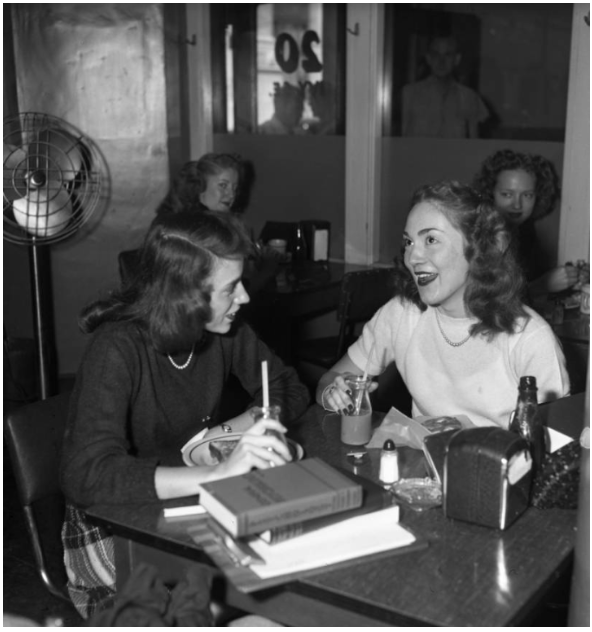

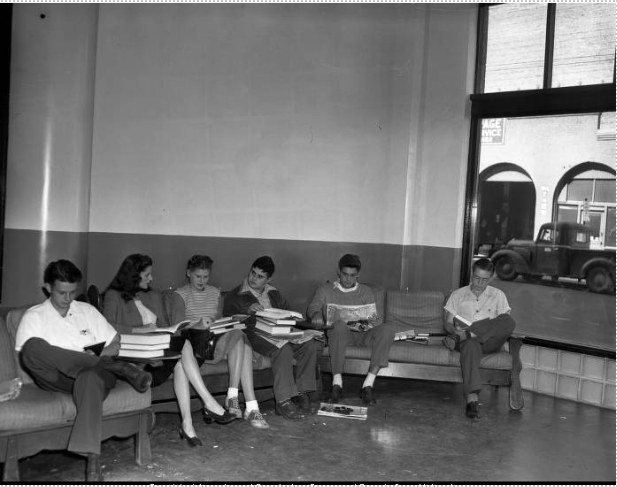

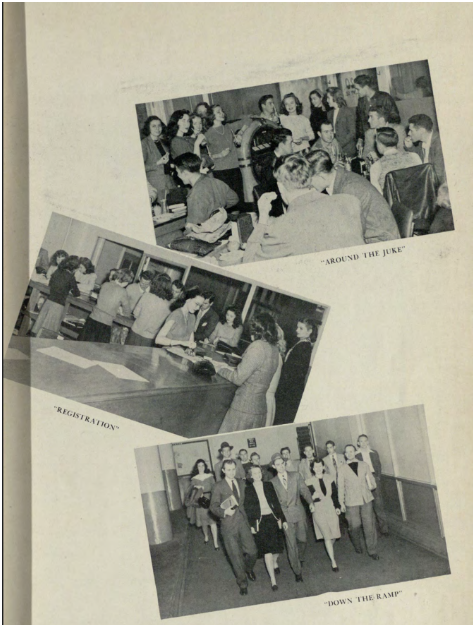

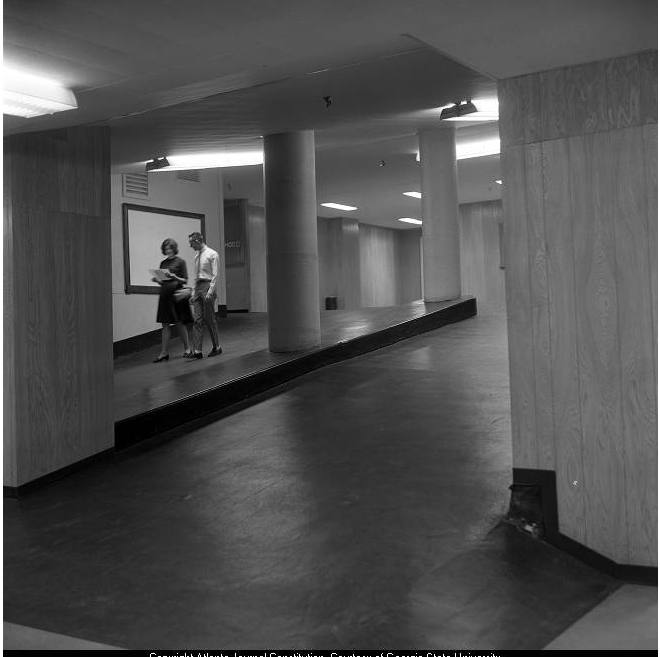

The first floor contained administrative offices and student amenities, including the Hurt Cafeteria, a library, and a bustling ”refectory” where students gathered to study, socialize, and obtain their course readings through the Blue Key Book Exchange. The refectory would remain a mainstay of Kell Hall until 2018.

A gym and, for a brief time, a bowling alley occupied the sixth floor — to the delight of students but a headache for the faculty and staff who occupied the floor below!

The bowling alley’s location on the sixth floor would indeed be short-lived due to the noise and inconvenience. Records indicate that that university moved the facility to its recreation center at Indian Creek Lodge by the mid-1950s.3

Ever-Changing Identity (and Names)

The period following WWII marked many changes for the growing downtown college:

1935-1947: The school operated as an independent college under the University System of Georgia’s Board of Regents. Known as the Atlanta Extension Center (or Atlanta Center), it consisted of both the Georgia Evening College (night school) and Atlanta Junior College (day division).

1947-1955: The school would be placed under management by the University of Georgia, a position under which Sparks and other Atlanta leaders chafed. During this period, the school became known as the Atlanta Division of the University of Georgia. It was during this period that the “Ivy Building” became fully operational as the school’s first permanent home.

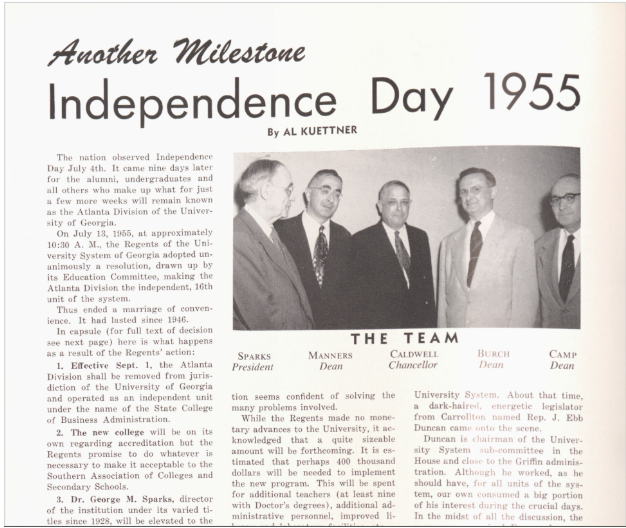

1955-1961: Georgia State finally becomes “Georgia State,” well almost, known officially as the Georgia State College of Business Administration, and again returning to its independent college status under the Board of Regents.

Post-War Growth

Atlantans soon became aware of the small college located in downtown, where there appeared to be growing need. The University System of Georgia continued its primary focus on developing its flagship University of Georgia in Athens some 75 miles away, and the Georgia Institute of Technology pushed to fill the post-war demand for science and engineering classes, solidly establishing itself in midtown Atlanta. To meet its demand, Georgia Tech would also open a satellite campus in Chamblee, which would eventually move to Marietta and become the independent Southern Polytechnic University (in operation until its merger with Kennesaw State University in 2015).4 While the Board of Regents attempted to turn its “Atlanta Center” into a junior college, hoping to funnel students to the Athens campus, Director Sparks followed the patterns of post-war demand, creating new nursing classes and expanding liberal arts offerings in Atlanta.

Meanwhile, students were beginning to home in on a unique culture at the downtown institution. Central to the school’s identity was the quirky building on Ivy Street. Director Sparks had hoped that the building’s ramps, the most noticeable architectural feature ported over from its time as a parking garage, would prove useful to disabled veterans returning from WWII. Unfortunately, as scholars of accessibility can now attest, the ramps were too steep to allow wheelchairs comfortable egress.5

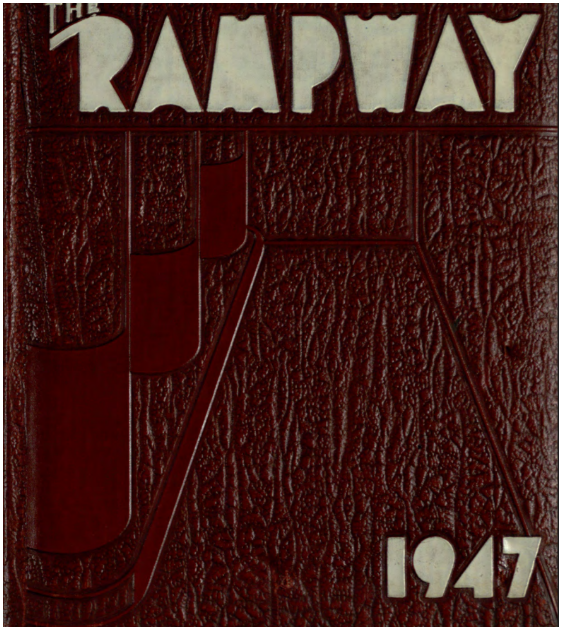

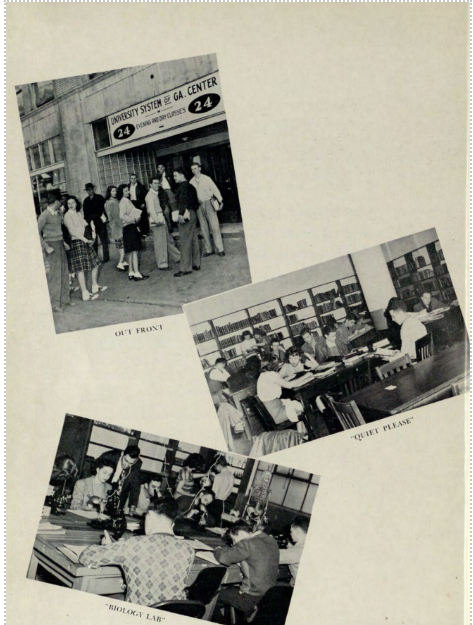

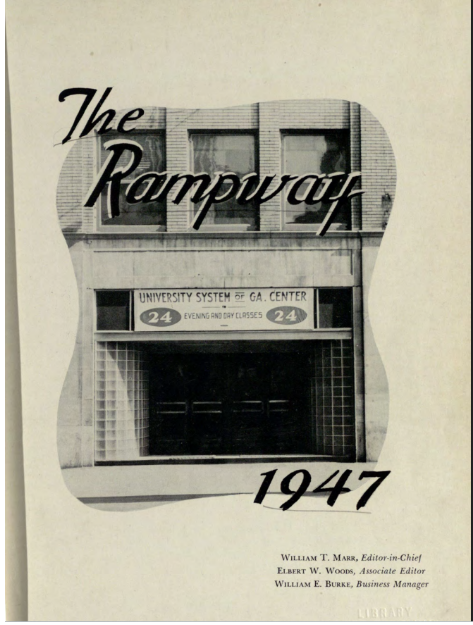

However, the majority of the school’s students embraced the ramps as a core part of their college identity. The first “Rampway” yearbook was published in 1947 and featured snapshots of student life centered at the Ivy Street building as well as advertisements for the school’s burgeoning offerings. Reflecting the school’s origins as an evening college and evolution to include a daytime junior college, the first yearbooks were called the “Nocturne” and the “Gateway.” In 1947, the yearbooks merged to become the “Rampway.” It was published under that name through 1996.6

During the 1950s, Director Sparks continued to promote the new school and its offerings to Atlanta-area business leaders and residents. Ironically, the school that had found a home in a former parking garage lacked parking for students and faculty. This probably became all the more pressing once the building of the interstate system completed Atlanta’s transformation into an automobile-dominated city, but Director Sparks did not let that stop his relentless push for growth.

Renovations were ongoing to meet student demands while minimizing inconvenience. By continuing to lease out office space on the first floor of the Ivy Building, the school would take in income to offset the costs of renovation. Ironically, Director Sparks’ adaptability and thrift had convinced the Board of Regents that “the state could have a public college in Atlanta at little expense.” The next two decades of growth would be marked by tensions between ambition and economizing, centered in the new building that would eventually be known as Kell Hall.

In 1952, Sparks demonstrated the school’s growth potential to an accreditation committee from the Southern Association of Colleges by showing them a site right behind the Ivy Street building that had been set aside for construction of the school’s first purpose-built classroom building (what would become Sparks Hall). Construction of the new building on Gilmer Street followed Sparks’ Ivy Street blueprint of leveraging war surplus (this time from the Korean War) and was completed by April 1955. The building’s opening received live prime-time television coverage by a former Evening College student, newscaster Douglas Edwards.7

The realization of this first “new building constructed by the school for the school” would prove a major factor for convincing the Board of Regents to grant the school its independence.8 On September 1, 1955, the new Georgia State College of Business Administration would commence its first semester as an independent public four-year college within the University System of Georgia.

Identity Crisis for the Independent Campus

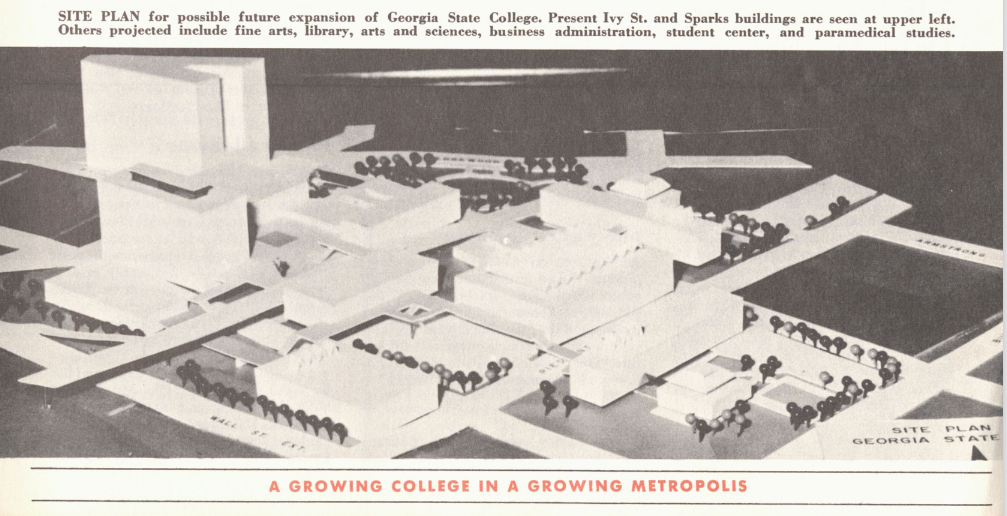

The new building that would be named for George Sparks on June 8, 1960, would be the first of a series built during the 1950s and 1960s. Visions for an expanded campus included a library and classroom buildings, and landscaped spaces for students to congregate.

The newly independent college had its sights set on emancipation from its identity as a “College of Business Administration.” Lobbying by alumni and faculty in the arts and sciences led to the school changing its name yet again to Georgia State College in 1961.

Meanwhile, Georgia State’s model of admitting “irregular” students, especially working adults who were older than the average college student and often the first in their families to pursue higher education, faced a major crisis during the period from 1950–1962 when Georgia’s Board of Regents adopted a policy of resistance to desegregation.

Director Sparks, who had been focused on catering to the needs of these “irregular students” and growing enrollment at the institution, expressed ambivalence about the impending desegregation crisis. While working to improve “campus life” through the renovation of the Ivy Street building, he downplayed its importance when discussing the potential impact that enrolling Black students might have on the school. Sparks emphasized the lack of residential halls and the school’s “mature and working students” as reasons why desegregation might not lead to unrest at the newly independent school. Still, he worked diligently to screen out faculty who might support desegregation using surveillance measures and avoidance of hiring professors from the North.9 Thus, Sparks’ last year as Director passed without the College admitting the first six Black applicants who applied in 1956.

However, the segregation/desegregation crisis was only just beginning to heat up. At the Federal level, the National Defense Education Act of 1958 required desegregation for schools to benefit from federally-subsidized scholarships. Even without federal subsidies, public higher education represented an opportunity for low-cost learning that did not go unrecognized by Black students across the country. Even in the 1960s, the cost of private colleges nearly doubled the cost of attending public institutions.10 In Georgia, Black students were faced with a choice between private HBCUs and very limited options for public higher education, so they began to exert pressure on the Board of Regents to desegregate the USG’s constellation of schools across the state.

Anticipating a flood of Black applicants to public schools, the Georgia state legislature and Board of Regents adopted policies aimed at preventing their enrollment. They threatened to close public schools and withdraw funding if they integrated, and eventually instated age limits and complex and subjective admissions standards aimed at making it almost impossible for Black students to attain successful applications. Among the requirements were alumni affidavits and “character” interviews, admittedly difficult for Black students to obtain in a highly segregated society.

Despite his support of these measures at the state level, Georgia State College’s new president, Noah Langdale, began to see their direct negative effects on the school by 1960. Georgia State’s enrollment declined by 25% from 1959 to 1960 with 1062 fewer students enrolled. Citizens across the state complained about the age requirements and draconian admissions procedures, especially at Georgia State which had a reputation for educating working adults.

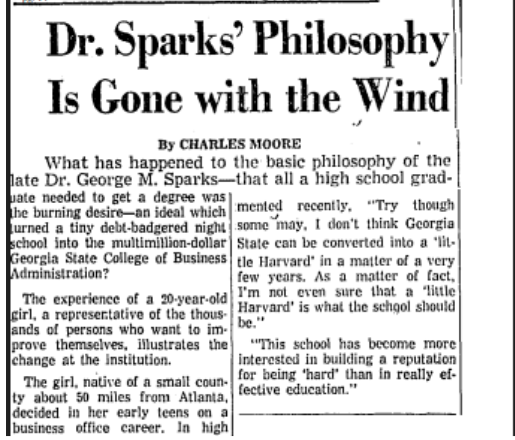

In a series of editorials in the Atlanta Constitution, Charles Moore emphasized the disservice the legislature’s attempts to prevent desegregation was doing to the people of Georgia, regardless of their race. In an editorial entitled “Dr. Sparks’ Philosophy is Gone with the Wind”11 he wrote:

Years ago, Dr. Sparks promised “if any Georgia high school graduate, willing to work, will come to our college, I will guarantee him a college education.”

Charles Moore, Atlanta Constitution

The next day, he followed up with another report12 in which he explained that

Students at Georgia State report that the student body has a large number of students for whom the urge to attend college came late. “Some had to work five or six years before they saw the need for college, or a way clear for them to go,” one student said. “But as it is now, they wouldn’t be able to get in.” There is currently no effort by any Negro to gain admittance to Georgia State. But it is expected any time. For, as one faculty member noted, there is no state-supported Negro college in Atlanta, where a third of the population is Negro.

Charles Moore, Atlanta Constitution

Summing up the impact of the desegregation crisis on Georgia State, Merl Reed wrote in Educating the New Urban South:

During the state’s struggle to prevent integration, both blacks and Caucasians lost educational opportunities. In addition, Georgia State’s abrupt abandonment of open admissions and its adoption of the highest entrance requirements in the system brought additional hardship. Besides being a self-inflicted wound, it harmed its own white constituency. It also invited comparison with the state’s earlier use of the “quality education” theme to protect the UGA law school from integration… Perhaps this experience foretold that Georgia State’s mission of reaching out and providing services to a wide variety of urban constituents could not again be easily abandoned.

Merl Reed, Educating the New Urban South13

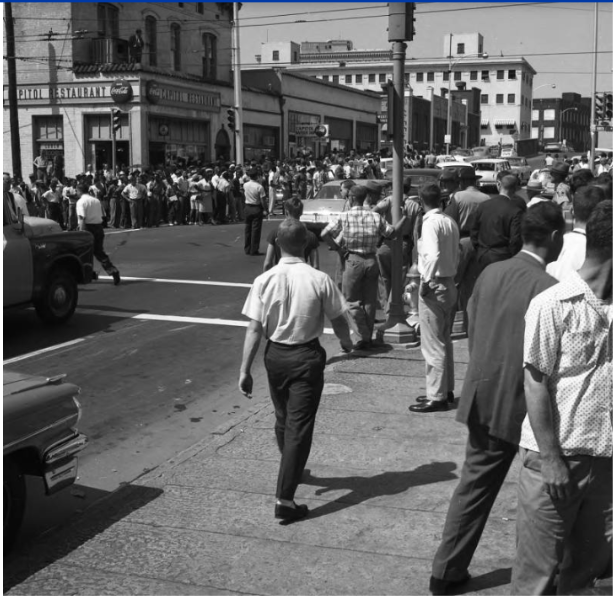

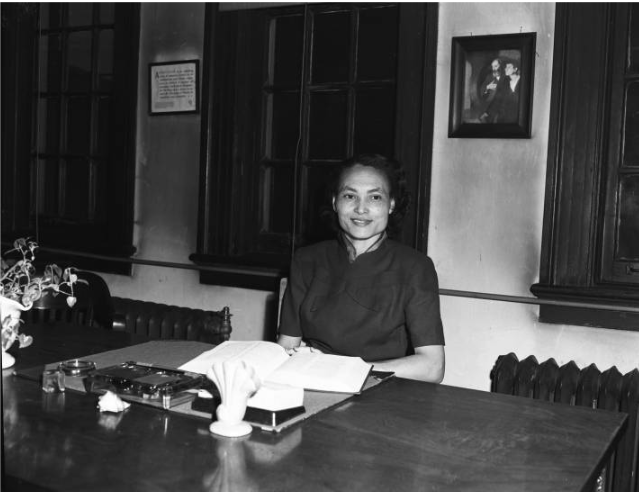

Ultimately, after the successful admission of Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes at the University of Georgia in 1961, and the state’s refusal to close its flagship university as a result, the legislature repealed its age law and Georgia State could no longer find excuses not to admit highly qualified Black students.14 In 1962, Georgia State admitted its first Black student, Annette Lucille Hall, a 37-year-old public school teacher from Rockdale County. The next year, six Black students enrolled, and the first African American faculty, Annie L. McPheeters, was hired in 1966. Georgia State had embarked on a transformation that would ultimately result in its becoming majority-minority by 2007 and priding itself on its ability to mentor and graduate low-income and minority students.15

Bursting at the Seams

After weathering the desegregation crisis and eventually bringing Black students and faculty to campus, Georgia State’s President Noah Langdale turned his attention to growing the school and improving its reputation.

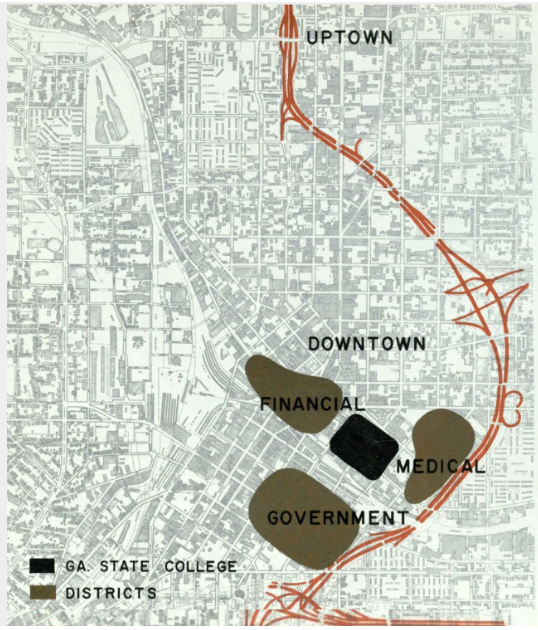

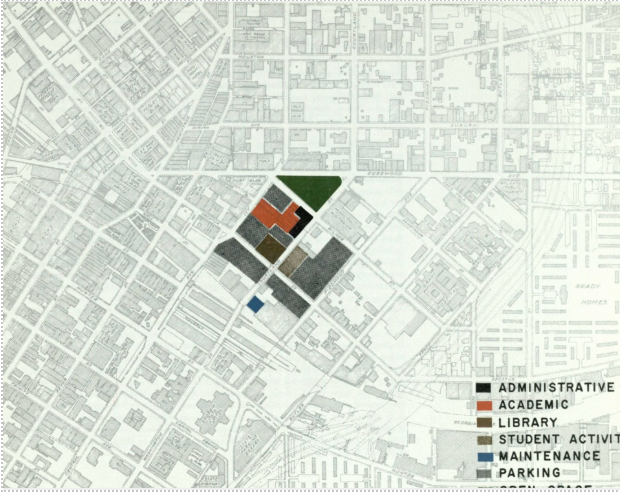

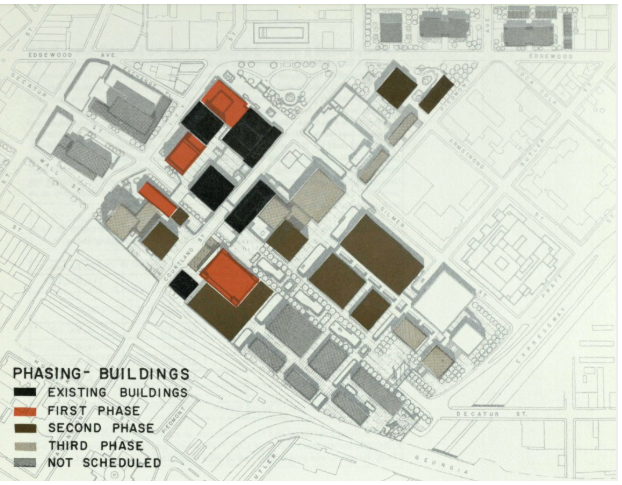

The Ivy Street building, the newly christened “Sparks Hall,” and a three-story library building that had opened in 1956 could no longer serve all the necessary functions of the campus, and a campus plan involving a combination of new construction and strategic purchases was unveiled in the GSC Alumni Newsletter in May 1962.

President Langdale leveraged Urban Renewal funding during the 1960s and 1970s for renovations, construction, and purchases, resulting in dozens of new spaces on the campus. Among the first renovations were the construction of new physics labs in the Ivy Street building which was officially renamed Kell Science Hall in 1964, in honor of Wayne S. Kell, the director of the original Evening School.

AJCP551-55kk, Atlanta Journal Constitution Photographic Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.

A grand vision for a “Platform Campus” was revealed in a 1966 Master Plan to create a sixty-acre “multi-level campus of tree-shaded plazas and pedestrian boulevards above the noise of city traffic.” In this vision, Kell Hall was given pride of place in a description of the school’s heritage:

The Georgia State College Campus has expanded from the old rampway garage, remodeled as Kell Hall, which is located at the end of Exchange Place on Ivy Street. This building is just two blocks east of Five Points, major node of downtown Atlanta and financial hub of the Southeast. The location has proven strategic, not only because of its convenient proximity to the business community, but also because it bordered on urban renewal areas which were in process of rapid transition. The latter factor, together with the interest of the Atlanta business community, has made it possible to secure additional area for expansion of the College in response to growing enrollment.

1966 Master Plan16

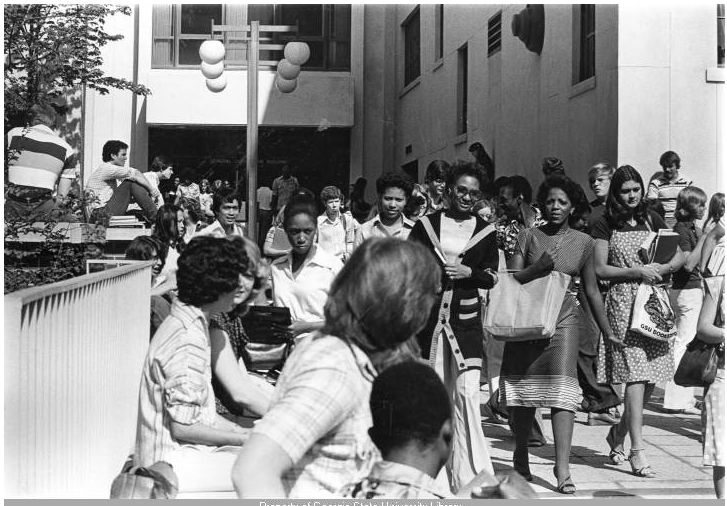

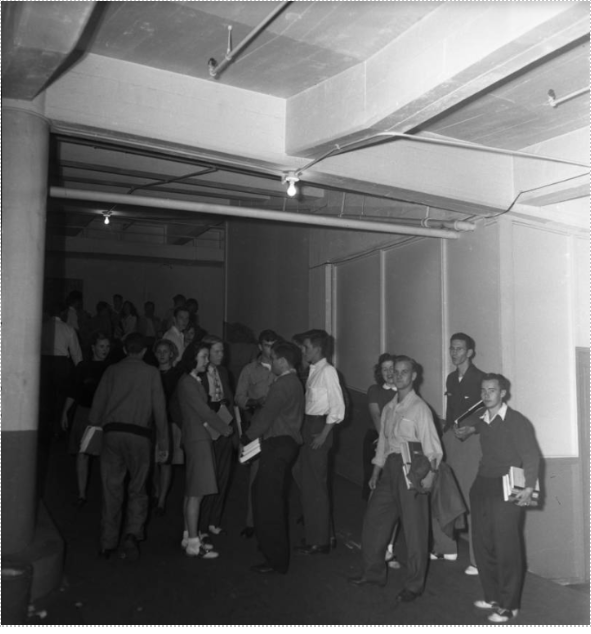

Even with all the growth, Kell Hall remained the center of campus, serving as a site for registration and student life throughout the 1960s and 1970s.

By 1969, Georgia State was offering Ph.D. degrees in business administration and psychology and its enrollment hit a milestone of 13,000 students. Chancellor George Simpson of the Board of Regents recommended university status, and the school officially became Georgia State University. For the next 20 years, President Langdale would continue to balance the demands of faculty, staff, students, and Atlanta constituents for degree programs, world-class facilities, recreational space, training opportunities and more as Atlanta would continue to grow into a business and cultural center in the second half of the 20th century.