Change of Fortune

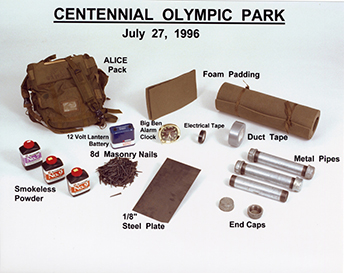

A little after midnight on July 27, a security guard named Richard Jewell, working on a temporary contract to patrol the Olympics, spotted an ALICE pack—a military-style vest—abandoned under the grandstand at Centennial Olympic Park. When no one claimed it, and facing the possibility of something going wrong when the band Jack Mack and the Heart Attack soon took the late-night stage, Jewell alerted his superiors and began evacuating some of the 15,000 park guests from the area. Around 1 am, 911 received an anonymous call that a bomb was about to go off, but operators didn’t send in the police because the caller hadn’t given an address. Twenty minutes later, the three pipe bombs in the ALICE pack detonated.

Nail shrapnel injured more than one hundred people. The casualties would have been higher except that the bomb had fallen sideways and for Jewell’s quick work to move people away. One woman, visiting Atlanta from Albany, Georgia, with her daughter, was killed, and a Turkish photographer running to cover the scene suffered a fatal heart attack.

SORT team investigators at Centennial Olympic Park preparing to sort debris from the park bombing, 28 July 1996, AJCNL1996-07-28-02b

It was not the first modern Games to be disrupted by violence; the 1972 Games in Munich had seen a terrorist attack unfold in the Olympic Village. The officials of the Atlanta Games honored those lost and injured in speeches over the following days and determined that the events should continue, which they did peacefully. In the meantime, the Federal Bureau of Investigation took over the case, attempting to identify the anonymous caller, create a profile of the bomber, and isolate any clues from the wreckage. But as days went by, hardly any evidence surfaced. And with no other leads, the FBI began to look at the man who had discovered the bomb in the first place: Richard Jewell.

Journalists attempt to question Richard Jewell outside his apartment complex, 1996, AJCNL1996-07-30-02c

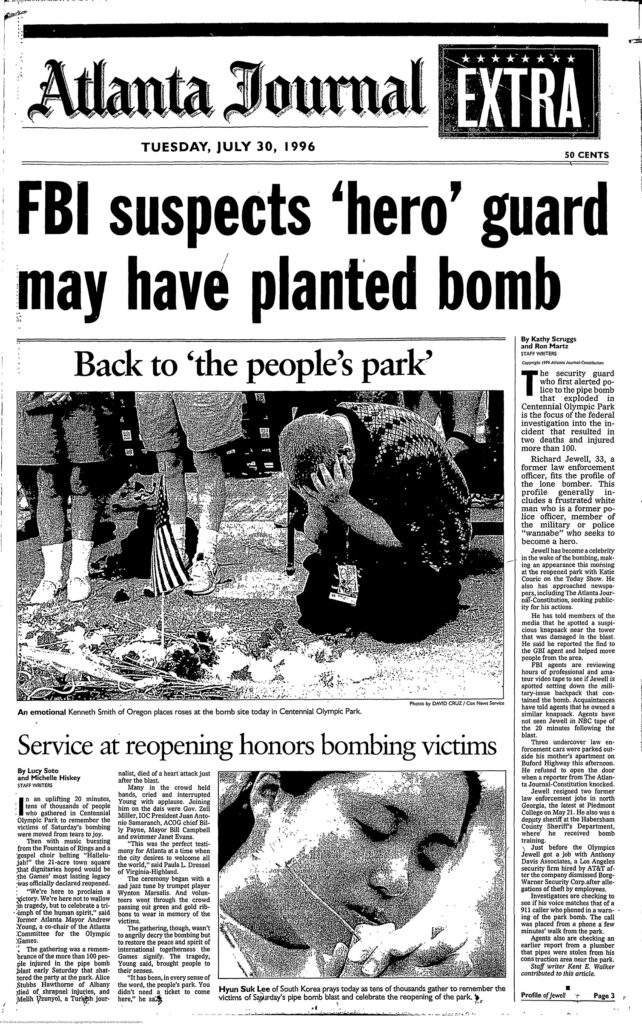

On July 30, working off a tip from the Atlanta police, the headline of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution proclaimed that “F.B.I. Suspects ‘Hero’ Guard May Have Planted Bomb.” With this, and for the next ninety days, the FBI’s only suspect became the subject of an enormous, antagonistic media frenzy. The Journal’s reporting was quickly picked up by CNN, who implied that fragments of the bomb had been found in Jewell’s home. ABC, CNN, CBS, and NBC reportedly rented a room in his apartment building to spy on him, and he was convinced that journalists were listening to his phone calls. Tom Brokaw speculated on NBC News that Jewell could “probably” be arrested, and Jay Leno compared him to the Unabomber. The new narrative seemed to be that Jewell, who had always been obsessed with being a real policeman, had planted the bomb so he could pretend to find it and get a hero’s recognition.

FBI agents brought Jewell in for an interrogation that they told him was practice for a training video. A search warrant for his mother’s home turned up nothing; a lie detector test revealed nothing. There would never be any evidence linking Jewell to the bomb. By October, the US Attorney was forced to state that Jewell was “no longer a suspect” in the Centennial Park bombing.

The overwhelming media attention lessened, but the trauma of being accused of planting the bomb would haunt him for the next decade. Every year, he laid anonymous flowers at the memorial for the victims, and in 2021, the City of Atlanta put up a monument to Jewell and other first responders near the bomb site downtown.

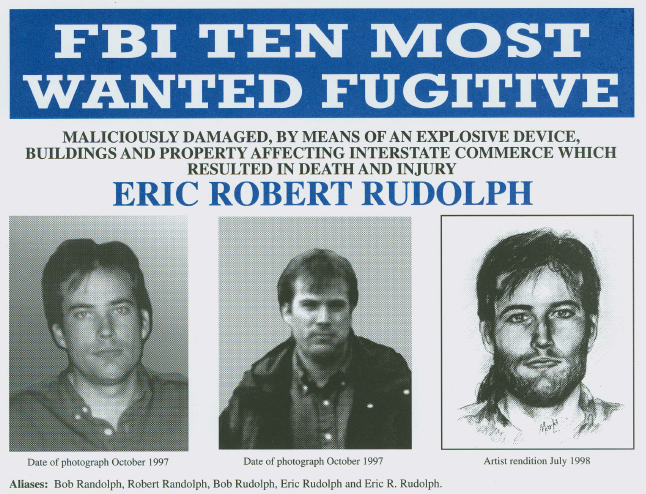

In 2003, a man named Eric Rudolph was arrested while digging through a dumpster in Murphy, North Carolina. Two years later, he pleaded guilty to federal charges of detonating the bomb at the 1996 Olympic Games. He had also set off bombs at family planning clinics in Sandy Springs and Birmingham, Alabama, and at a gay nightclub in Midtown, and at the time of his arrest had buried more than 200 pounds of explosives around North Carolina. Rudolph was a Christian extremist who, he claimed, had attacked the Games to protest the American government’s sanctioning of socialism and abortion rights. He is serving multiple life sentences at a federal prison in Colorado. He was twenty-nine when he bombed Centennial Park.

Richard Jewell died in 2007, from complications of heart disease, in his home in Woodbury, about 70 miles south of the site of the Games. He had successfully sued CNN and NBC for libel for their 1996 commentary, but his defamation suit against the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, the newspaper that set off the frenzy, had foundered and was dismissed after his death. He was forty-four.