Izzy A Bigot?

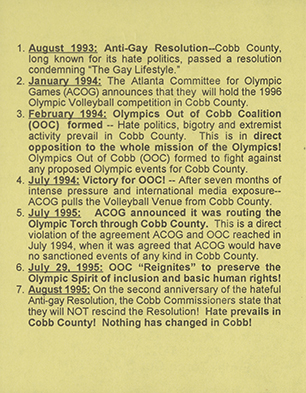

In the summer of 1993, a theater in Marietta, Cobb County, staged an adaptation of the Terrence McNally play Lips Together, Teeth Apart, which featured references to gay couples (all offstage) and AIDS. A countywide controversy ensued over this public discussion of homosexuality, and in direct response to the play—and in an indirect response to the rise of AIDS-related news and Atlanta’s recent passing of a domestic partnership registry that allowed the unmarried partners of city employees to receive workplace benefits—Cobb County commissioner Gordon Wysong drafted a non-binding resolution that stated that the values of Cobb County explicitly excluded the “gay lifestyle.” Wysong’s commission passed the resolution (effectively, an official opinion) and eliminated the county’s art funding.

The suburbs of Cobb County had been the destination for much of Atlanta’s white flight in the 1980s. As a result, the county was majority-white and a stronghold of insular conservatives that prided itself on a culture of local business, Christianity, and so-called family values. Cobb’s 1993 resolution didn’t come with any legal consequences for the gay community, but, as the Atlanta Constitution noted, such a statement “amount[ed] to official government condemnation of a whole group of people.”

Then, at the start of January 1994, it was announced that the Galleria in Cobb County would host the Olympic volleyball preliminaries. For many residents, this was an unacceptable prize for a place that had declared them undesirable. Atlanta had won the bid for the ’96 Games largely through Andrew Young’s pitch of the city as progressive and cosmopolitan, or “too busy to hate.” Any locations outside Atlanta that hosted an Olympic event would be seen by the world as multicultural by association. This deeply upset the gay community: by hosting Olympic volleyball, Cobb County would get the credit for being open-minded while it was acting, in their eyes, like an old-fashioned Southern backwater.

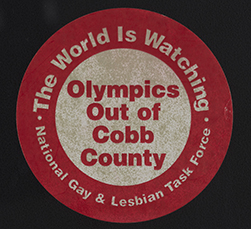

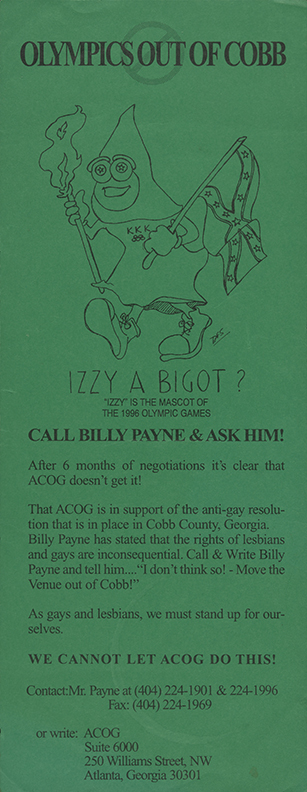

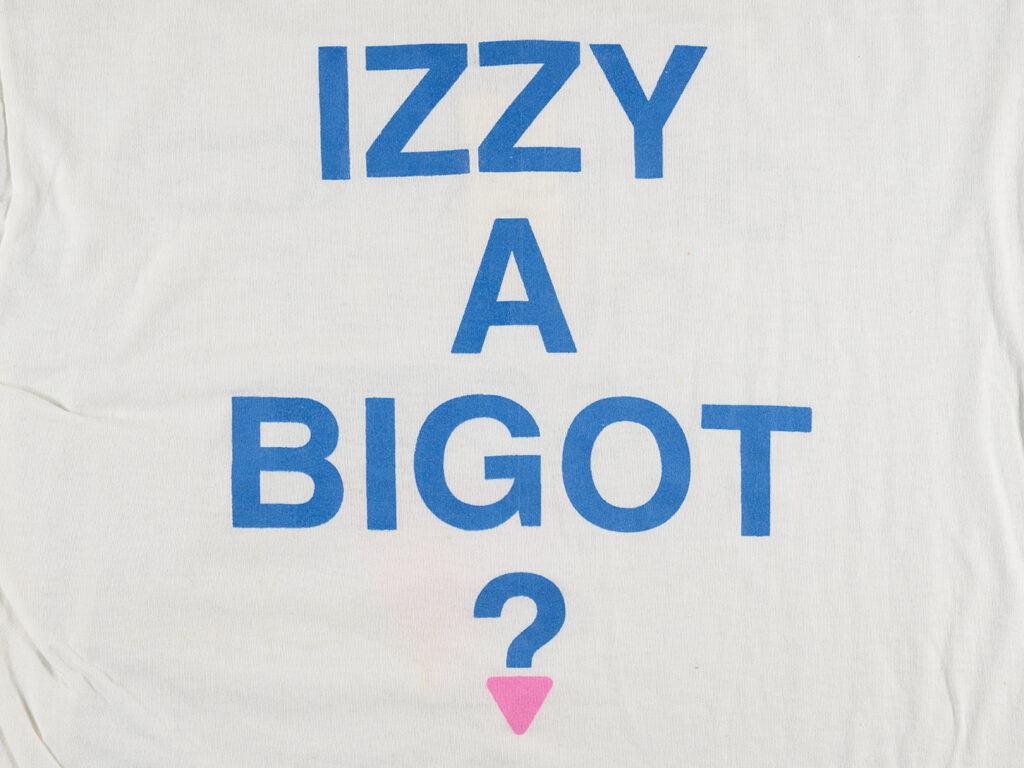

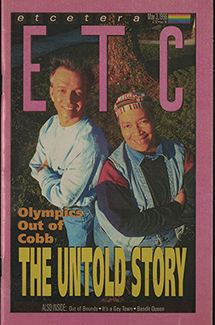

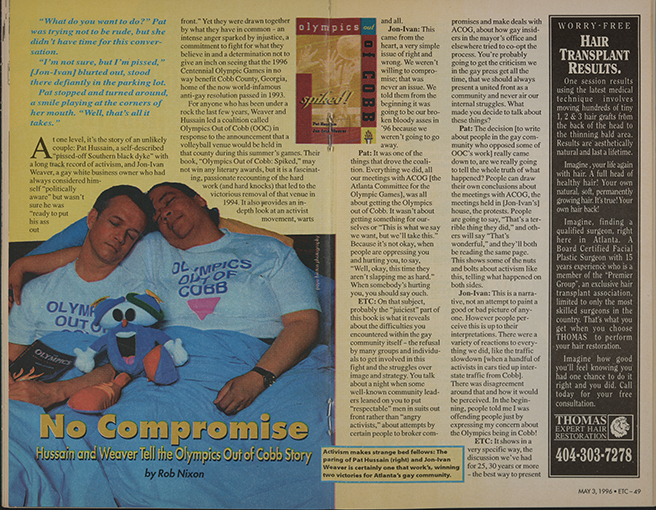

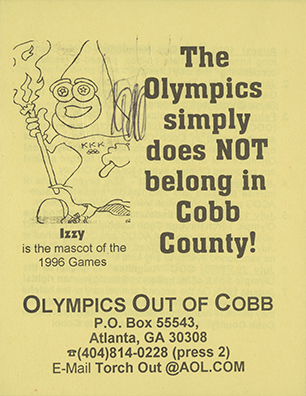

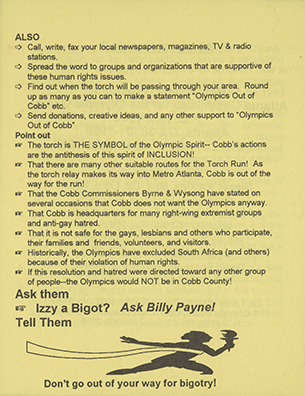

Led by Jon-Ivan Weaver, a white Cobb County resident who had never protested before, and Pat Hussain, a Black Atlantan with a long résumé of queer activism, a group of local protestors called Olympics Out of Cobb set out to make themselves an unignorable nuisance until the Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games agreed to move volleyball to a new location. At the official unveiling of the cauldron design, two protestors unrolled an “Olympics Out of Cobb” banner across the stage. The activists hijacked the image of Izzy, the Atlanta Games’ mascot, and made T-shirts and posters asking “Izzy gay? Izzy straight? Izzy safe in Cobb County?” then dressed him in Klan robes, asking “Izzy a bigot?” They held press conferences, candlelight vigils, 400-person rallies, and a mock-torch run and rented billboards along the highway to gain national attention. On the afternoon of a Braves game, they drove in a line down I-75 at the minimum legal speed limit, piling traffic behind their cars with pink triangles on the hoods. The activists’ goal was to make ACOG realize that moving out of Cobb was in its own self-interest—that staying was a threat to its portrayal of Atlanta as accepting of all people—and that they would not stop protesting even once the Games began.

Congressmen John Lewis and then-Vice President Al Gore wrote letters of support; diving gold medalist Greg Louganis, who had recently come out, gave a statement encouraging the International Olympic Committee to “do what’s best for the athletes.” Finally, in July 1994, Shirley Franklin, the managing director of ACOG, and a future Atlanta mayor, who had met with Weaver and Hussain during the protests, announced after months of hedging that the volleyball preliminaries would be moved out of Cobb to the University of Georgia in Athens.

In 1996, Olympics Out of Cobb had to restart their protests when it was announced that the torch run would be going through Cobb County, which had made no move to rescind its resolution. The activism worked: no official Olympic activity was ever held in Cobb. It still received huge amounts of tourist dollars, and the anti-gay resolution was never officially rescinded. But the queer activists had demonstrated how powerful creative grassroots protesting could be: they had moved the Olympics.