Triumph of the Human Spirit

Billy Payne didn’t include the Paralympic Games as part of his pitch to the International Olympic Committee for Atlanta to host the 1996 Olympics—but then, it wasn’t yet expected that the same city would necessarily host the Paralympic Games. It wasn’t even guaranteed that the Paralympic Games would be held after their Olympic counterparts at all: the International Paralympic Committee was equivalent to the IOC, but the two organizations weren’t obligated to work together. If someone wanted their city to host the Paralympics, they had to compile a separate bid, organize their own funding, and secure their own buildings for training, housing, and exhibiting the Games. In the lead-up to the 1984 Olympics, Los Angeles hadn’t put in a bid to host the Paralympics at all, and they ended up being held in New York. So, when Andrew Fleming and Alana Shepherd pitched Atlanta as the host for the tenth Paralympic Games to the IPC in 1992, they’d already been negotiating for money and space for years.

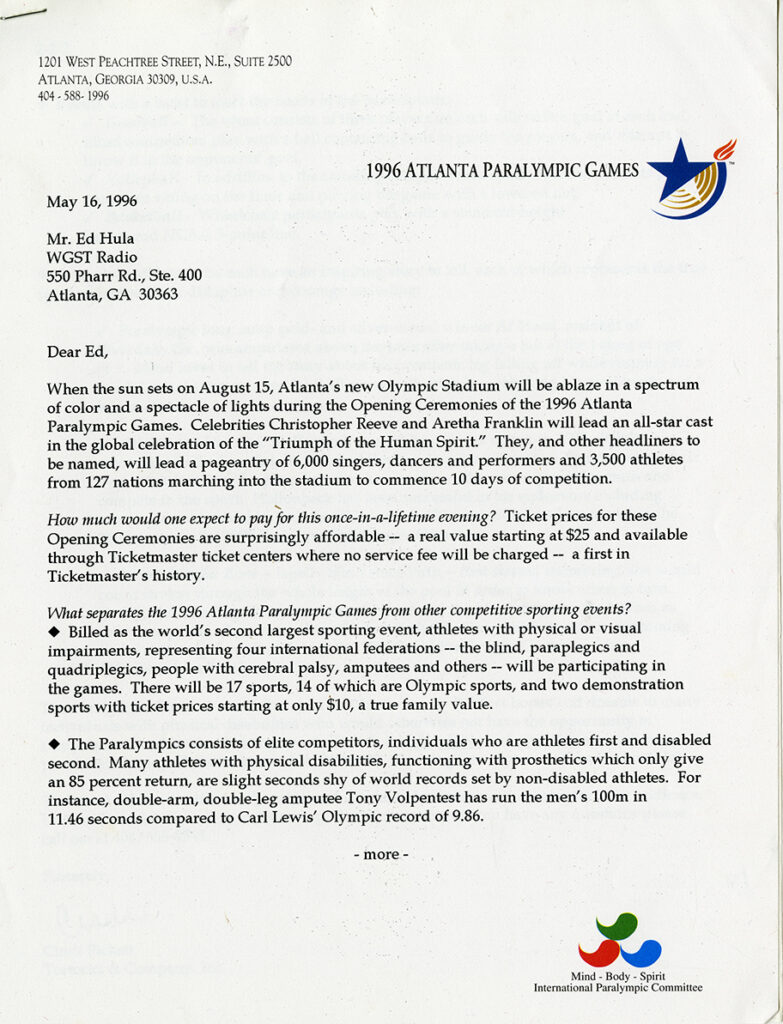

In 1991, Fleming and Shepherd had approached ACOG, Payne’s organizing committee, to try and negotiate for any funds they could from the millions in Olympic resources, but ACOG, citing a tight budget, declined to donate anything. They did agree to share their vendor spaces and provide personnel support, which provided the Paralympic planners with an infrastructure. After winning the bid from the IPC—in part because they could demonstrate support from the Olympic planning committee—Fleming and Shepherd then struggled to gather a comparable amount of corporate funding. Alana Shepherd was obligated to approach official Olympic sponsors first, but many of these companies both declined to donate to the Paralympics and—exercising an exclusivity clause in their Olympic contracts—forbade her from soliciting sponsorships from their rivals. Working the press, Shepherd called these companies the “Sinful Six” (Visa, John Hancock Financial, Anheuser-Busch, Bausch & Lomb, Sara Lee, and McDonald’s) and eventually secured enough corporate donations, sponsorships, and federal funding to launch the Games in late August without them.

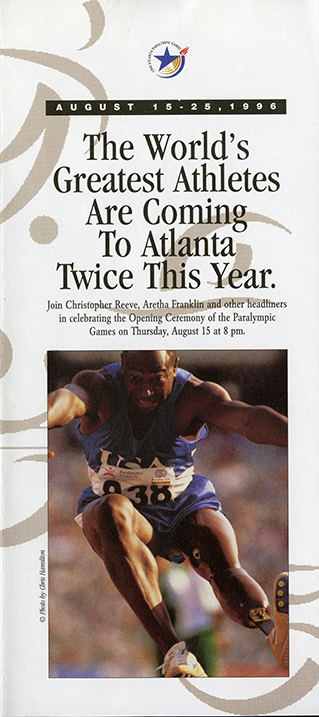

From the 16th to the 25th, the first televised Paralympic Games in history introduced most able-bodied Americans to athletes with disabilities—and the term “Paralympians”—for the first time. Four thousand athletes competed in 19 events and broke 269 world records. The Paralympian mascot Blaze, a brightly colored, energetic phoenix, and the Atlanta ad agency BrightHouse’s “What’s your excuse?” campaign helped bring in more than 400,000 attendees. And the popularity of the Atlanta Paralympics in the summer of 1996 helped usher in the current iteration of the familiar two-part event: the IPC and the IOC have agreed that through the end of the 2020s, the same city will host both the Olympic and the Paralympic Games.