Welcome to Our Brave and Beautiful City

No one expected Atlanta to win the bid to host the 1996 Olympics, including most Atlantans. The ’96 Games would be the one hundredth anniversary of the modern games, and Athens, Greece, home of the modern Olympiad, had put in a bid. Atlanta’s international reputation in the late ’80s, as much as it had one, was of a medium-sized southern city that had burned down in a civil war and suffered brutal racial struggles in the 20th century, on top of the stereotypes of poverty and crime that dogged most American cities. Atlanta was the first Black-majority municipality in the States and had elected its first Black mayor in 1974, but the city’s population had dropped steeply leading up to the ’90s as white Atlantans fled the city for the expensive suburbs of Cobb County. As a result, Atlanta’s public infrastructure had severely worsened, its public housing deteriorated, and its poverty and crime risen. It seemed unlikely that the International Olympic Committee could be persuaded to think that Atlanta was up for the job, but a lawyer named Billy Payne steered an aggressive committee that was determined to do exactly that.

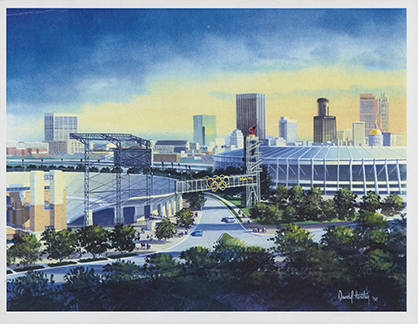

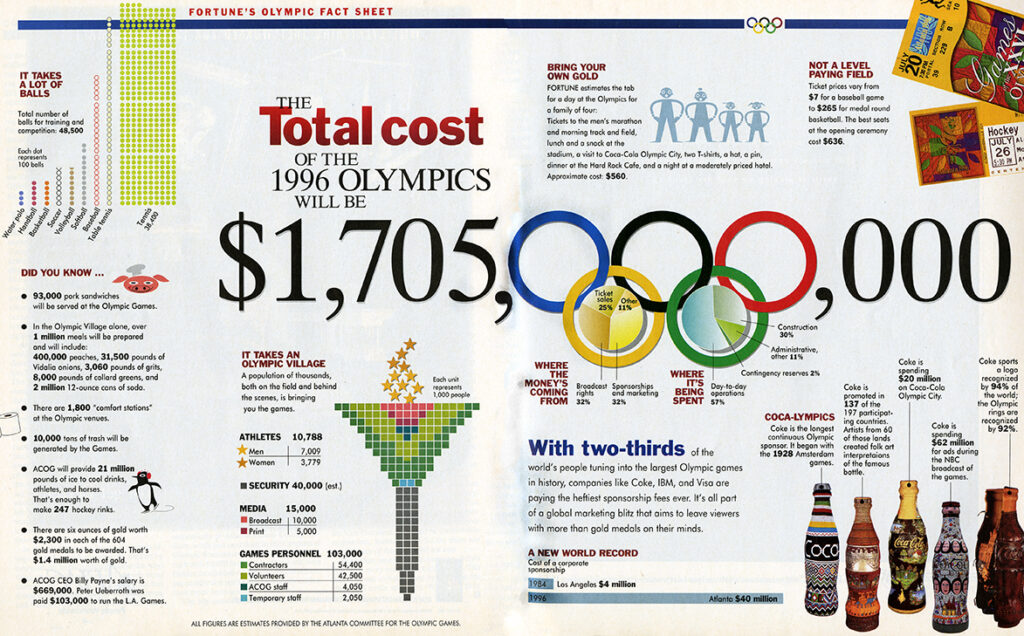

After Atlanta won the bid over Athens in September 1990, the Atlanta Organizing Committee, headed by Payne and incorporated as the Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games (ACOG), outlined an ambitious plan to both host the athletic competitions and their international guests and to revitalize the city. This project required a nearly never-before-seen cooperation between the city’s public and private spheres, which operated largely along racial lines, with a privately funded budget based on corporate sponsorship, television rights to the Games, and ticket sales. Not only did ACOG have to oversee the construction of official Olympic sites, such as the Village where the athletes would live, and designate dozens of venues around Georgia as competition grounds, but they had to come up with a proposal to cosmetically modernize a stagnated inner city. Preparation for the Summer Olympic Games, including improvements to public walkways and plazas, hotel renovations, the construction of Centennial Park, and the expansion of Hartfield International Airport, would cost almost $2 billion.

What the administrators, investors, athletes, journalists, workers, volunteers, visitors, and native Atlantans got was a temporary transformation of downtown Atlanta. The events of the Games, from the planning years before to decades after the Closing Ceremony, would be cause for celebration, community-wide protests, national triumph, international devastation, and throughout it all ambivalence and confusion as to what “Atlanta” meant.

AJCNL1995-10-19b

Marching band performing at the Olympic race during an I.O.C. tour of the city, “The Seed and Feed Machine Abominable band perform some of their unusual ‘marching’ formations for the thousand participants in the 10k and the IOC and Atlanta Organizing Committee as part of the pre-race hoopla.” 8 April 1990, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archive, AJCP217-012c

Plans to rebuild the infrastructure of key Atlanta neighborhoods meant displacing the low-income residents who had lived there for decades. Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority had to upgrade its entire system on a severely limited budget and prepare to move millions more riders than it was currently capable of. Months, then years, elapsed without any decisions on a strong look of the Games—how Atlanta would present itself to its visitors as a historical southern city with a majority African-American citizenship—and fears that the designs would become so abstract that any idea of Atlanta would be hopelessly lost seemed to be confirmed with the debut of the Summer Games’ mascot, an amorphous little creature called Whatizit. To make matters even more challenging, a hosting site in Cobb County faced massive protests from the queer community over its prejudiced anti-gay legislation. And a bomb detonated in the middle of the night halfway through the Games, killing two people and triggering a frenzied, months-long media harassment of an innocent man.

Gymnastics coach Bela Karolyi carries Kerri Strug to the Olympic podium, 1996, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archive, AJCP582A-028a

Muhammad Ali preparing to light the Olympic caldron, 1996, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archive, AJCP582A-028b

The Games themselves unfolded powerfully, too. Muhammad Ali lit the torch during the Opening Ceremony, the first time many Americans had seen him since his diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. The US team won gold in the inaugural women’s soccer tournament. Nineteen-year-old gymnast Kerri Strug stuck a second vault on an injured ankle to secure American gold over the Russians.

Ukrainian Olympic gymnast Lilia Podkopayeva during her floor routine, 1996, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archive, AJCP582A-028k

Journalists complained about slow transportation and tacky commercialization; electronic kiosks broke down, and maps had to be updated and reprinted overnight; and the overwhelming corporate sponsorship minimized any real sense of a southern identity, much less one of Atlanta itself. But after the Olympic and Paralympic Games were over, the city had turned a profit of almost $20 million, and Atlanta would forever be able to say it had successfully hosted one of the world’s most prestigious events. Thirty years later, the summer’s legacy for Atlanta is still complicated. Was hosting the Games ultimately just an opportunistic business venture, or was it motivated by a real desire to show off “the city too busy to hate”?