The Power of Our Dream, the Legacy

Success or failure?

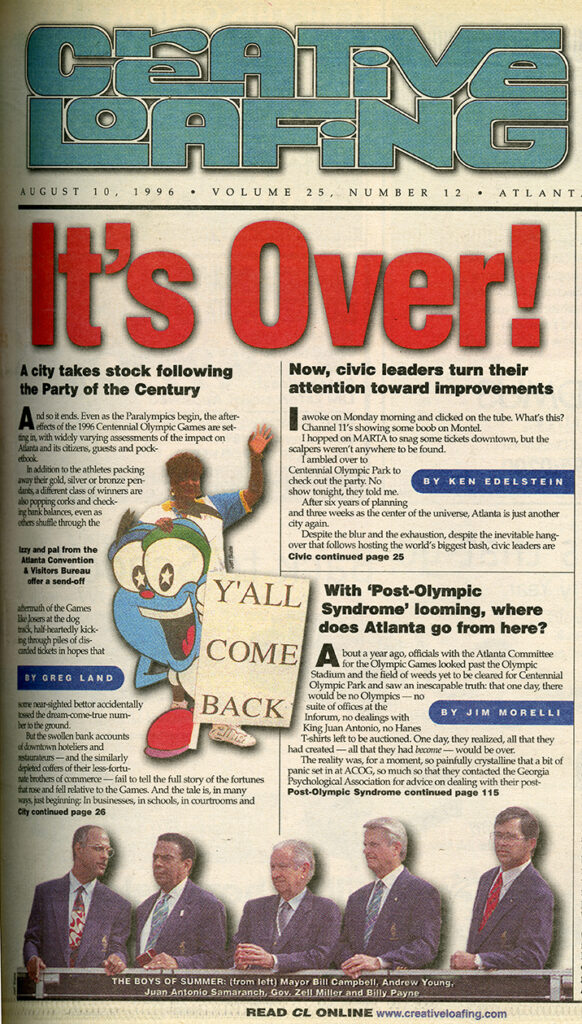

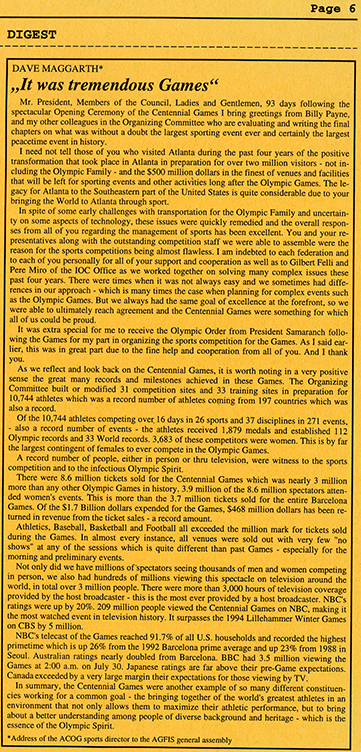

During his closing address, the President of the International Olympic Committee, Juan Antonio Samaranch, dubbed the 1996 Atlanta Games the “most exceptional” Olympics. It was his first-ever departure from calling his host’s Games the “best ever,” and many Atlantans—and visiting press—took it as his veiled disapproval of the way the city had put on the Olympics for the world.

In many ways, the Atlanta Games were exceptional. The surprise host city had no iconic building, like an Eiffel Tower or Empire State Building, or architectural style, such as Greece’s columns, that the rest of the world could recognize in art or advertisements. Its organizers had boasted of its southern hospitality as seen in abundant hotel rooms and restaurants, but Olympic tourists (and locals) found the city strangely culture-less as they wandered downtown and had to spend most of their money at the hundreds of small vendors along sidewalks or inside giant corporate sponsor tents (all the while, lacking even public bathrooms). The 1996 Games were the first to incorporate city-wide access to online technology, but the IBM systems for information, mapping, and translation were glitchy. They were the first Olympics to include public transportation in the cost of a ticket, though Atlanta’s MARTA system struggled with the Games’ temporary new grid. And the “Atlanta Way” of doing business that frustrated so many Georgians—a bureaucratic sprawl of ever-multiplying committees and authorities, mixing business executives and politicians with clashing goals—resulted in one of the most financially successful Olympics of the modern era: the Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games made a profit, and the city took on no debt.

But whether the legacy of the 1996 Games in twenty-first century Atlanta is positive or negative depends on who you ask. Urban developers who sought the expansion of the city’s busy core, and business leaders who wanted to advertise Atlanta as the corporate capital of the American southeast, would say that the Olympics put the city on the world’s map. But inside the so-called Olympic ring, the city itself did not get “fixed” in a lasting way: the infrastructure of downtown Atlanta is deteriorating again, and the poverty class that so worried politicians in the late 1980s and 1990s is still growing.

Historically, Atlanta has struggled to maintain a balance between the needs of public service and private businesses. The cooperation between these two spheres in planning the 1996 Olympic and Paralympic Games—sometimes contentious, sometimes disorganized—treated six million out-of-towners to almost thirty days of festival, pop culture, and the highest level of sporting competition in the world. But once the celebration was over and the tourists—and journalists—had gone home, nearly every aspect of life and business in the city went back to how it had gone before, which, for Atlanta, meant the public and private sectors no longer worked together. All the public has retained of the Games are the stadium, Centennial Park, the torch, and a bomb site memorial. It’s much harder to say if there were any lasting gains for small businesses or for the locals who had lived in neighborhoods thrust into the Olympic spotlight, many of whom were moved out of their homes to make room for the Games and now had nowhere to return to. After the Olympic moment passed, the Atlanta machine went back to its old ways of dividing races and classes, where business looks out for business and politicians struggle to combat decades, even centuries, of racist policies.

So, was the whole thing just an Izzy-esque computer glitch? Was it a mistake for Atlanta to bid on the 1996 Games? Would any other American city have done better under similar pressures and with similar resources? And could—or should—Atlanta ever be chosen to host the Olympic Games again? It’s entirely possible that it could, just as it’s possible that the cultural message might be different this time: Atlanta could somehow advertise itself as something specifically, coherently, and undoubtably southern and exciting. But unless those who organize, pay for, and pull off the Olympics in the future take some lessons from the past, it’s entirely possible that when those next exceptional Games were over, Atlanta would end up, once more, right back where it started.