The Atlanta Student Movement

“The young Negro students gained more desegregation in 24 months than the NAACP had gained since 1909” – Excerpt from a speech given by Lonnie King before the General Services Administration, February 25, 2013

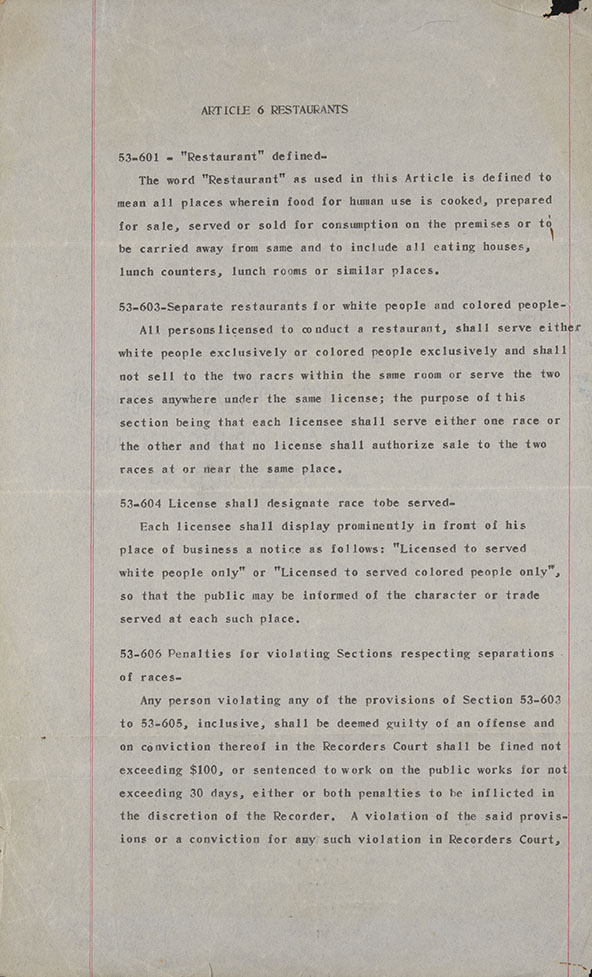

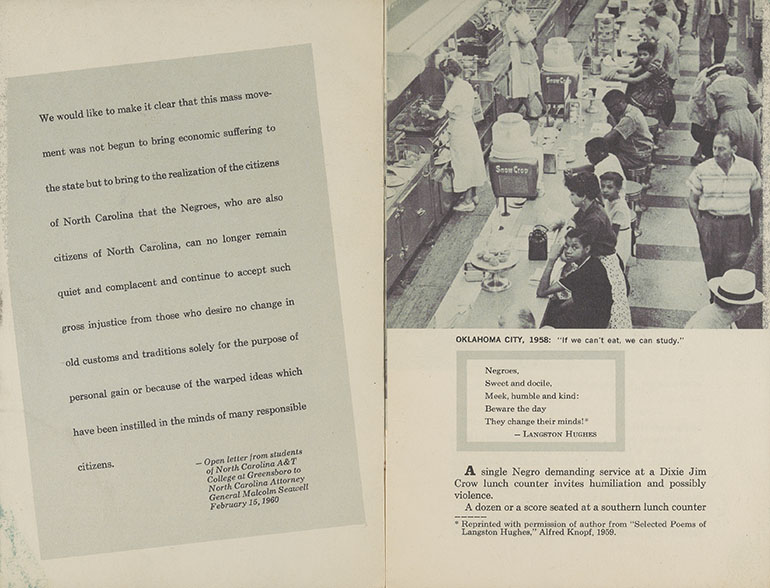

King, Bond, and a growing group of other local students wanted to try something similar to bring attention to the issue of segregated lunch counters—and department stores, entrances, buses, and effectively all facets of public life—in downtown Atlanta. King and the others approached some of the established figures of civil rights activism in the city but were told that the preferred way of dealing with any specific issues that arose because of segregated businesses was through private conversations with the white business owners.

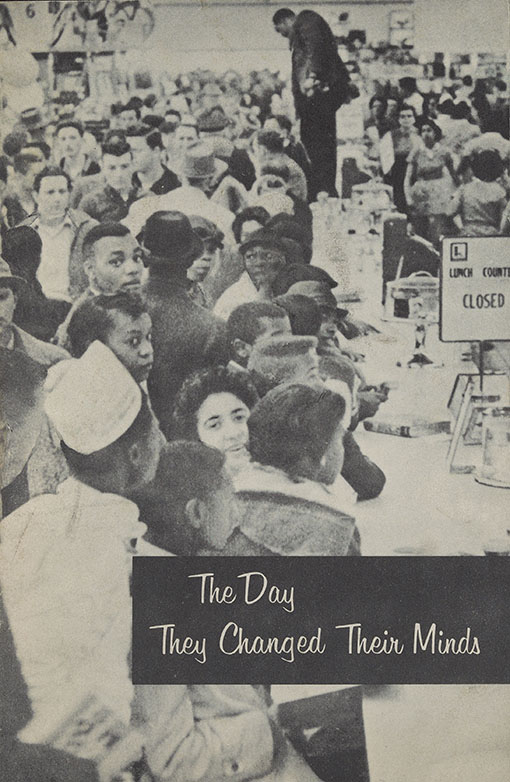

“Lunch-counters were the metaphor for the dissatisfaction of the young masses, which forced the older Negroes to take a stand for justice” – Excerpt from a speech given by Lonnie King before the General Services Administration, February 25, 2013

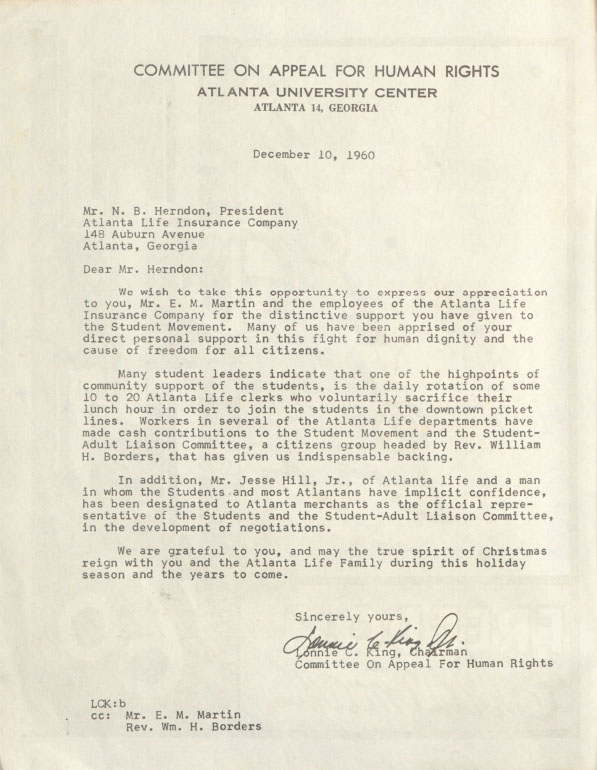

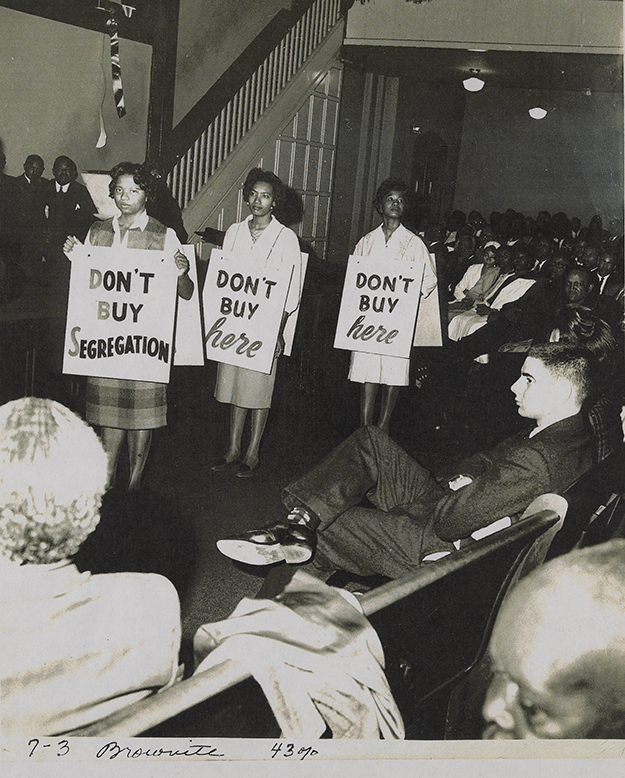

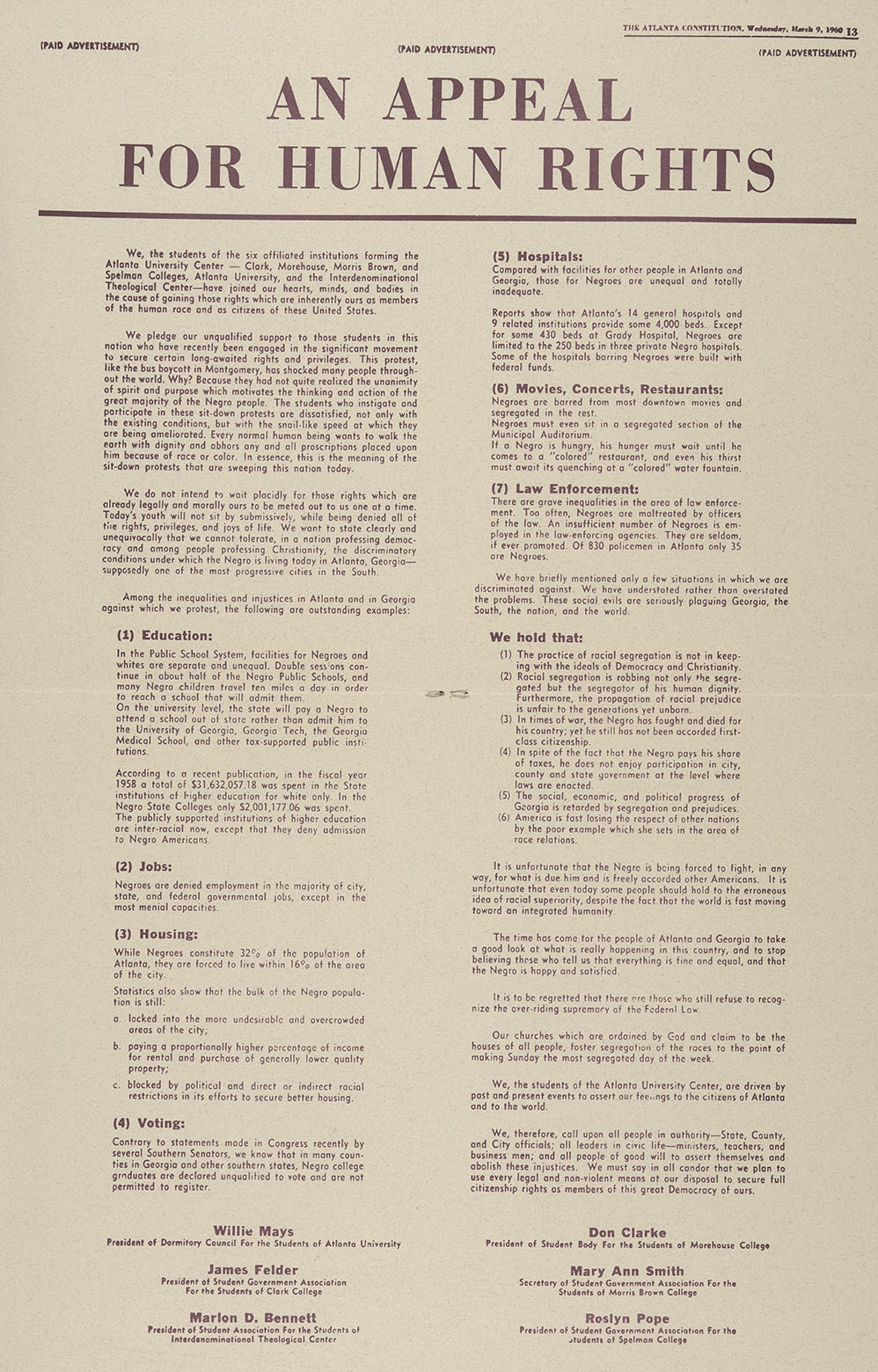

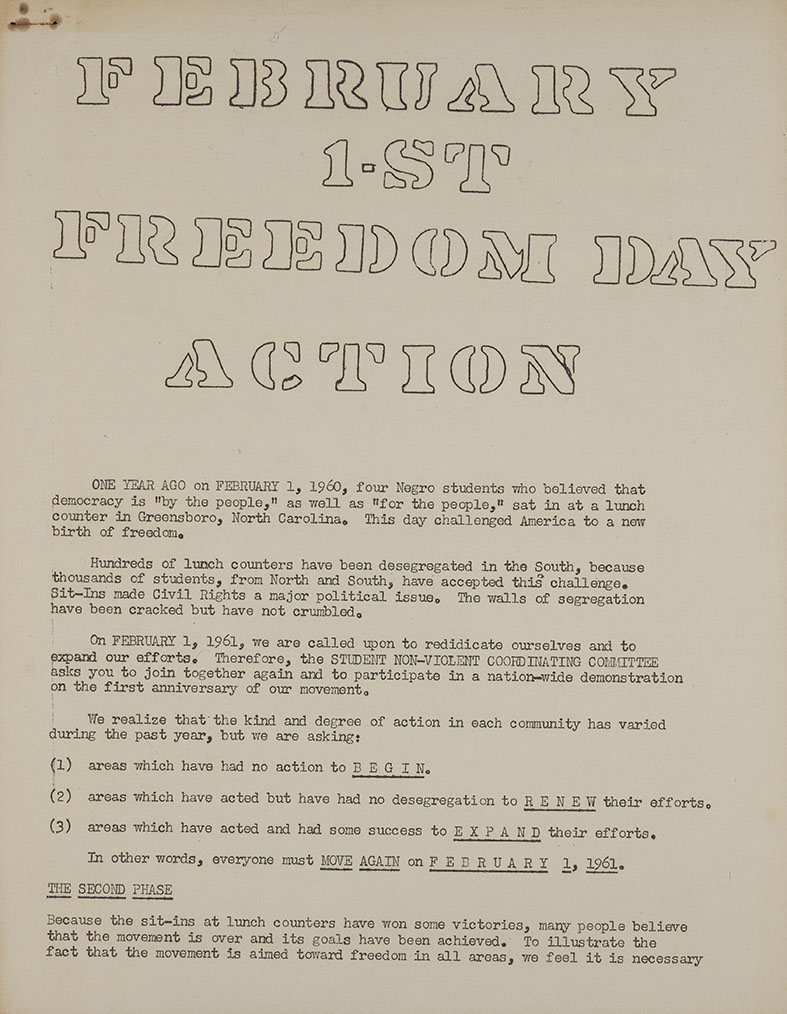

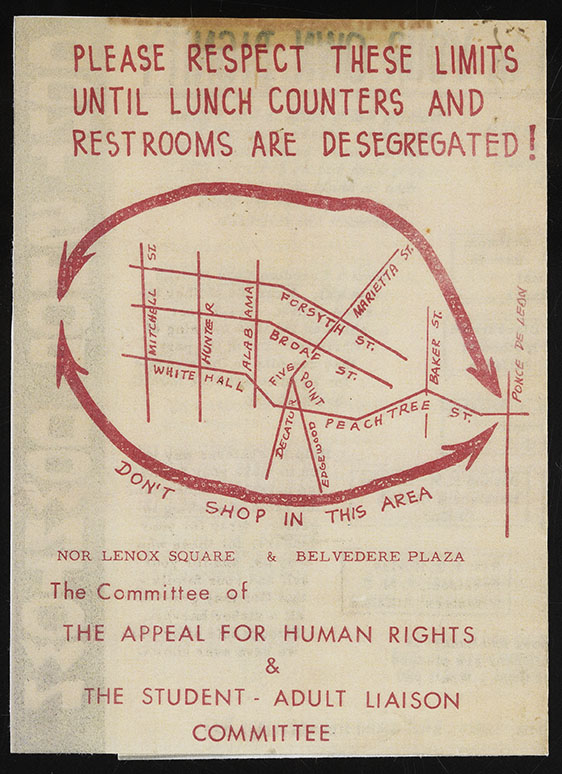

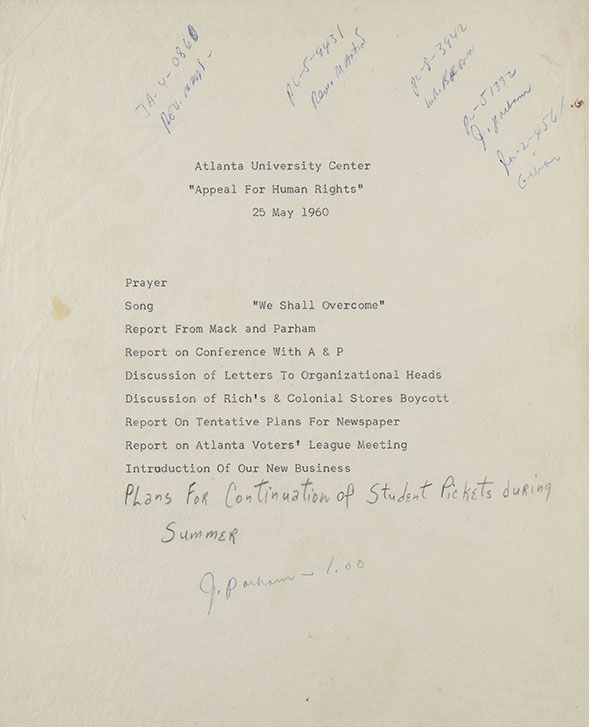

To the young Black students of 1960, this approach was no longer acceptable; they started planning a citywide sit-down campaign without such endorsements. Lonnie King was named chairman of the newly formed Committee on Appeal for Human Rights, and under his supervision, Spelman student Hershelle Sullivan drafted “An Appeal for Human Rights.”

This manifesto, which outlined the daily degradations that African Americans were still experiencing in the Jim Crow South, was published in the Atlanta Constitution as an advertisement and was rapidly reprinted throughout the region, eventually even in the New York Times. On March 15th, the student campaign began, and what would later become known as the Atlanta Student Movement was born.

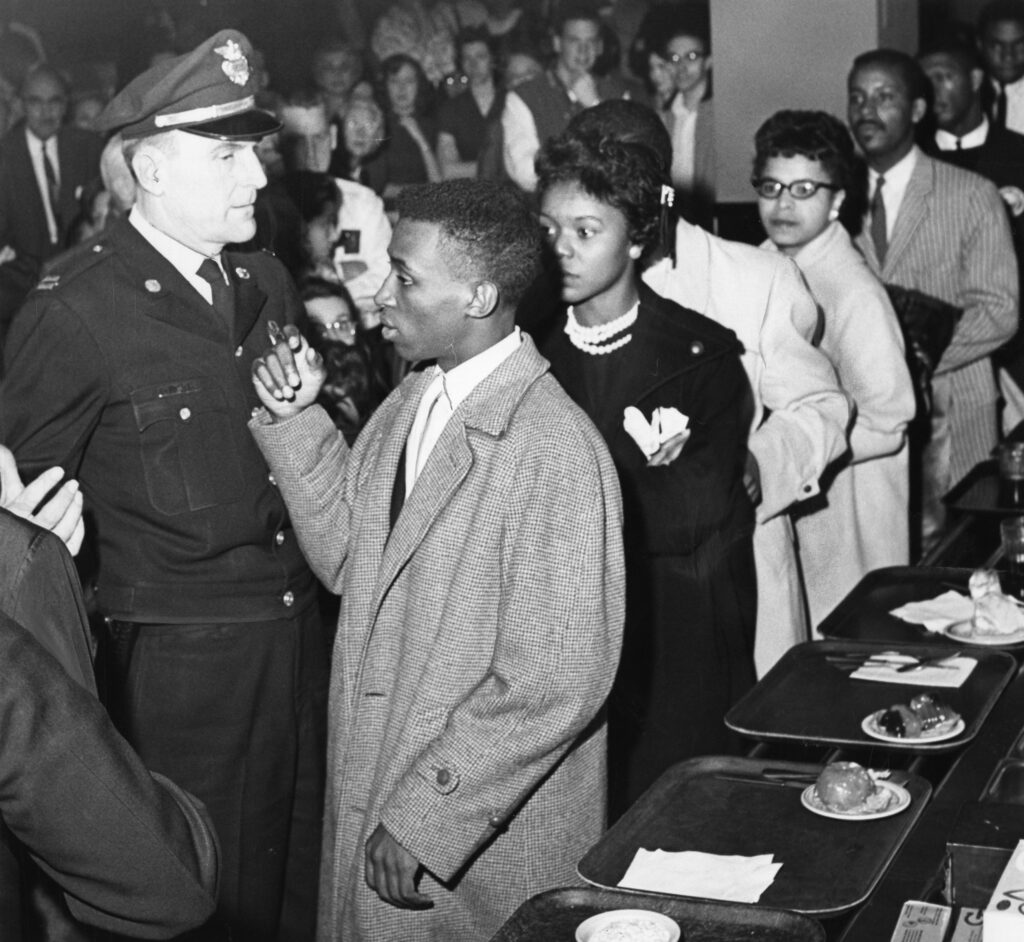

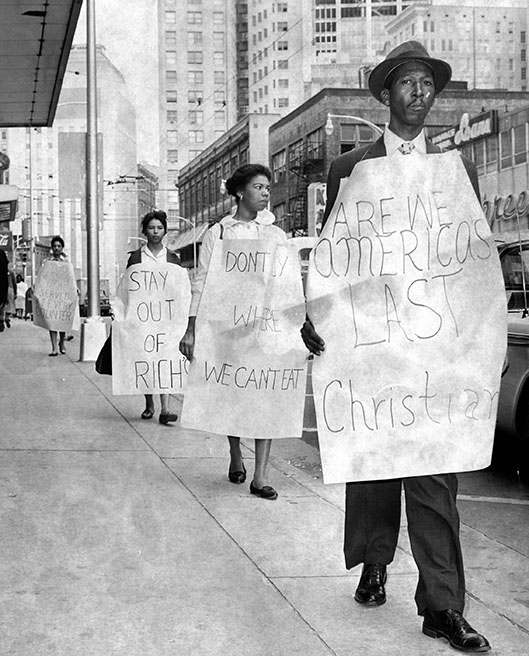

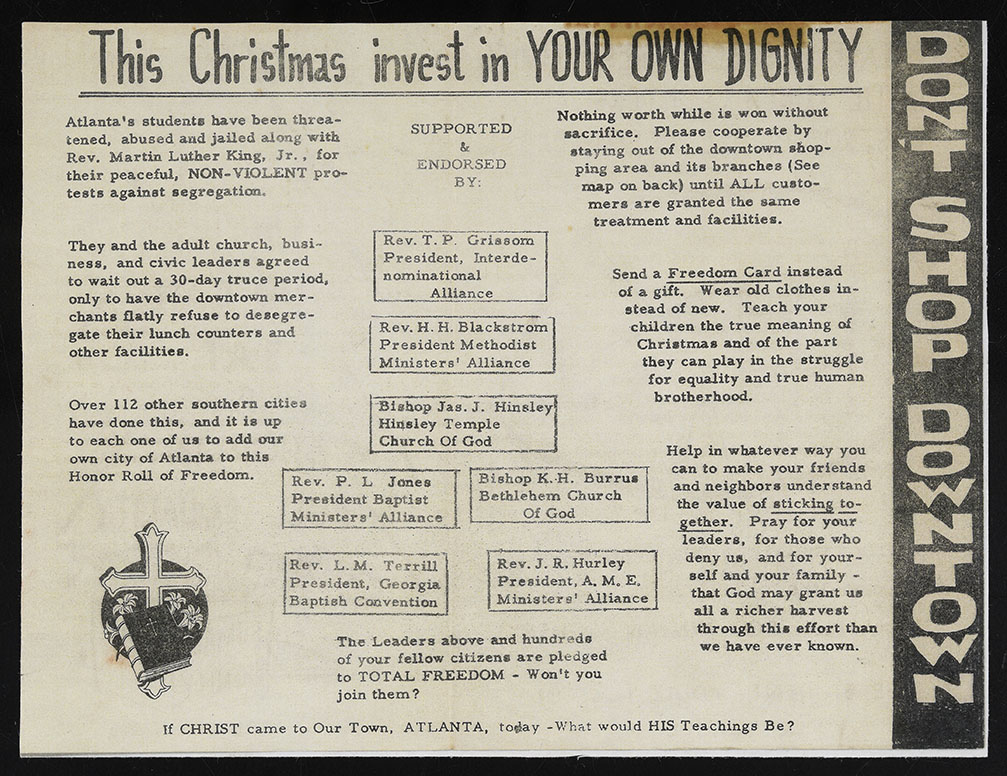

After Lonnie King preached to his fellow activists, they took their seats at lunch counters inside such popular department stores as Rich’s. They ordered food or coffee; when white staff refused them service, the students stayed put. Soon, white counter-protestors (often advertising themselves as members of the Klan) sprang up outside the stores; a series of editorials in Atlanta newspapers tepidly praised the students’ goals but criticized their quietly assertive methods. Over the next year, the young participants in the Student Movement would be harassed in their seats and frequently arrested, but there were so many of them—and they were so well-coordinated throughout the schools—that the protests continued without interruption.

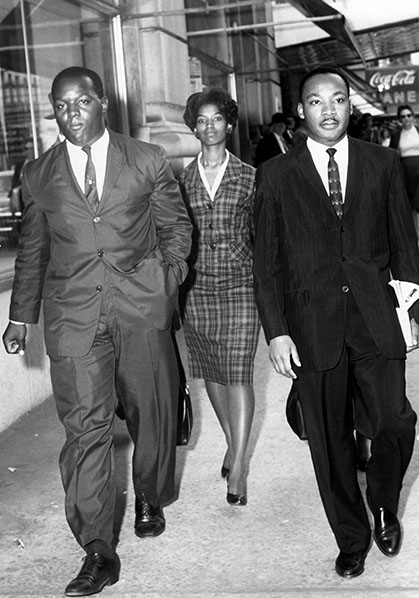

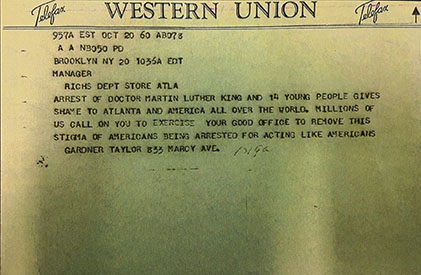

When Lonnie King convinced Martin Luther King, Jr., to join a sit-in at Rich’s, the two of them, alongside Spelman students Hershelle Sullivan and Marilyn Pryce, were photographed while being arrested outside the store. It took an intervention by John F. Kennedy to get Martin Luther King, Jr. released from jail, and many Americans’ shock of seeing such a famous nonviolent activist get arrested alongside the students spurred on the student movement.

By the spring of 1961, civil rights leaders in Atlanta had reached out to the white business elite and brokered their own deal to end citywide segregation. The students, who had just pulled off a year of unbroken protest in their community, felt betrayed at this exclusion; public spaces in Atlanta would still desegregate long after many other cities in the deep South, and it was not until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that integration became federal law. But the efforts of Lonnie King and the Atlanta Student Movement helped show a generation of young activists across the south, and throughout the country, that they could bring about real change in their community.