AFSCME Atlanta Local 1644 Protest

The American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) is the largest union for public service employees. By the 1960’s, AFSCME had ten different locals in Atlanta serving a variety of different public employees at the local and county level. Local 850 served the Atlanta Municipal employees, which included the city’s sanitation workers.

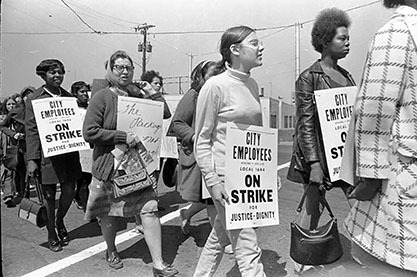

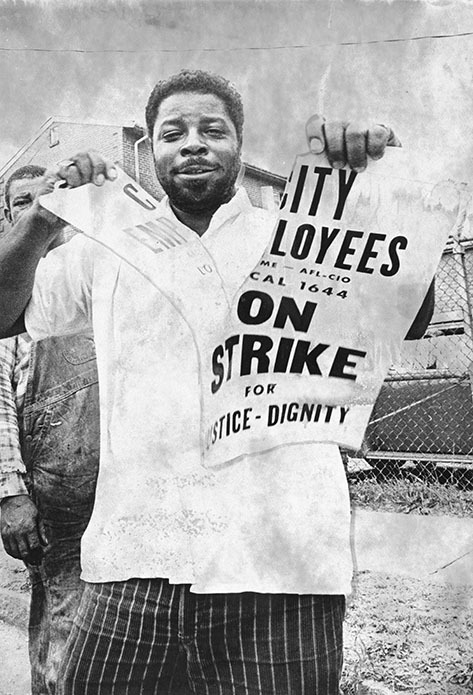

Frustrated by discrimination, poor working conditions, and poverty-level pay, 100 of Atlanta’s African American sanitation workers walked off their jobs on September 3, 1968. Five days later, over 700 sanitation workers went on strike. While the largely white local and district AFSCME leaders did not support their African American union members, AFSCME International representatives and Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) did, and with their support, the striking workers were able to come to an agreement at the end of the 10-day strike that included a 14.5% wage increase. AFSCME International’s leadership saw this victory as an opportunity to restructure the local and remove its racist leaders. The successful negotiations and the strike’s end were also seen as a victory for the city and its mayor, Ivan Allen.

Less than three years later, on March 17, 1970, AFSCME workers, supported by AFSCME and the SCLC, walked off on strike for 37 days over a wage dispute. Unlike the previous mayor, Ivan Allen, the recently elected Sam Massell was aggressively opposed to unions and fired the striking workers. Mayor Massell framed his opposition as an economic issue rather than a civil rights issue, and he maintained support from Black community members, while Local 1644 did not. By April, the mayor and the striking sanitation workers were able to come to a deal: all of the workers would be rehired, the lowest paid workers would receive a 4.5% raise, and the city would study worker reclassification with the possibility of an additional 550 employees getting raises. This was seen as a victory for Mayor Massell, as this agreement cost the city $100,000 less than a previous proposal.

Due to working in excessively cold conditions and having their pay docked, Local 1644 began a wildcat strike in January of 1977, which escalated to 900 workers going on strike on March 28, 1977. Local 1644 was pressing for a fifty cent per hour wage increase but Mayor Maynard Jackson, Atlanta’s first Black mayor, was against it. Mayor Jackson had previously supported Local 1644 in the 1970 strike and was elected mayor with help from Local 1644.

Like the 1970s strike, the striking workers lacked the support from the community that they had in the 1968 strike, and they were unable to build a coalition of support. Jackson had the support of white civic and business leaders and the Black middle class and was able to frame the strike as an irresponsible action by leaders who did not have the workers best interest at heart. Instead of the strike being seen as part of the Civil Rights Movement, it was instead seen as a labor dispute. On April 26, 1977 the strike ended and most of the workers were rehired, but at a lower wage. This was a victory for Jackson and a blow to workers in Local 1644.

In addition to the collection that Local 1644 donated, we have other collections that help tell the story of AFSCME Local 1644 and their strikes: Marc R. Levinson was a journalist and news editor of Creative Loafing and his papers contain material related to Local 1644’s strike; J.W. Giles was the Director of AFSCME District Council No. 14 from 1967-1968; and the AJC Photograph Collectionand Tom Coffin Photographs contains coverage of the strikes.