Data is Evidence

There’s much to learn from the numbers.

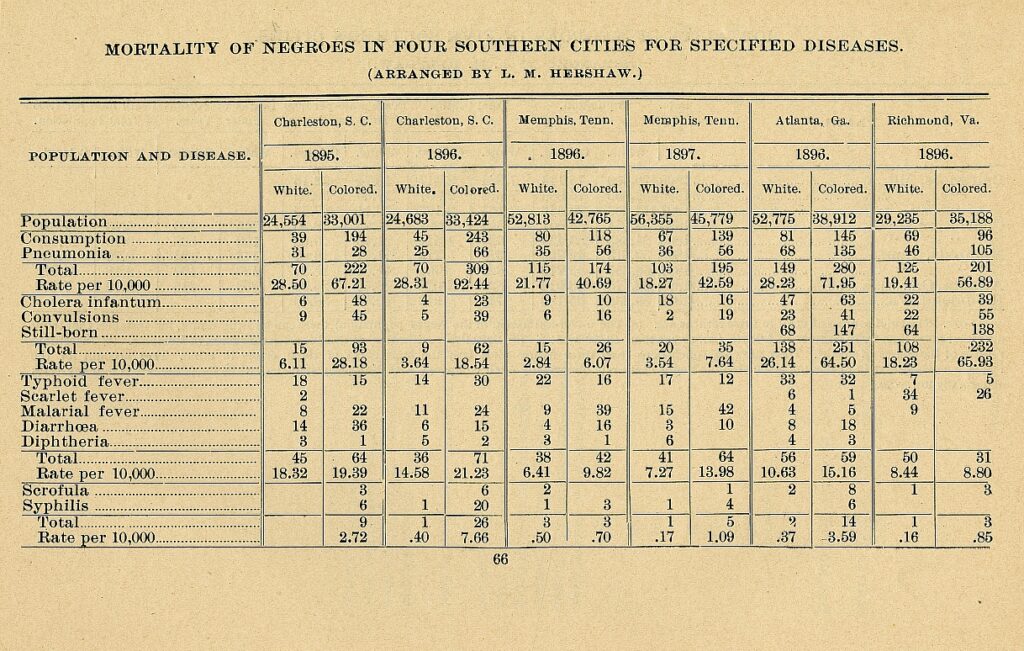

We need data to answer the question, “How many minority persons are affected by a disease or condition and why?” These numbers are needed to unmask public health problems affecting minorities and poor Americans in order to figure out how best to address them.

Past data reports, while useful, did not have the ability to document health disparities. The 1985 Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black and Minority Health made it clear that disparities in the burden of illness and death experienced by minority groups were not related to racial inferiority, but to social and economic conditions. Even now, data are not available for all minority groups or for all diseases and conditions that influence health.

Data provide the evidence we need to develop tools to address minority health issues. Improving the way we collect data and asking the right questions are essential to achieving health equity for all Americans.

It’s hard to tell the story without the facts.

Although information has been collected on health for a long time, gaps in data can frustrate our attempts to focus on communities at greatest risk for poor health. Examples of what is missing include information on racial/ethnic characteristics of communities, since much of the health data collected historically had information classified as only white and non-white.

It wasn’t until the 1970 Census that respondents were able to provide their own race or ethnicity – before that year race/ethnicity was decided by the data collector. This information is needed to monitor equal access to housing, education, employment, and other areas, for populations that have experienced discrimination and differential treatment because of their race or ethnicity.

For most health conditions, no national information is available for Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders, Native Hawaiians or Hispanics/ Latinos. That has made it more difficult to determine changes, positive and negative, that have occurred over time among these groups. The Office of Management and Budget, which sets the standards for federal data, set out five minimum categories in 1997 for race – American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and White – and two categories for ethnicity: Hispanic or Latino and Not Hispanic or Latino.