Loss of Traditional Foods

Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, Department of the Interior. War Relocation Authority. NWDNS-210-G-C402

As early as the 1930s, U.S. government food assistance programs provided processed commodities as food supplements to American Indian families. Communities that once provided for their own food and survival needs became dependent on the government for food. Products that were not a part of the traditional Native diet such as sugar, wheat flour, canned meats, soups, juices, pasta, rice, cereal, cheese, peanut butter, corn syrup, and vegetable oil became diet basics.

Dependence on these foods and limited access to healthy food alternatives created a shift in diet and, with it, a dramatic decline in health. The decline in farming and other traditional activities led to increased sedentary behavior and less physical activity. This created a high risk for obesity and related diseases. Within a generation, the problem of obesity replaced the problem of malnutrition. In addition, the destruction of long-standing food and agricultural systems and the replacement of indigenous foods with a diet composed primarily of modern refined foods became the centerpiece of the diabetes problem. By the end of the 20th century, one in eight Native Americans had diabetes, a rate twice that of the non-Indian population.

Early Hawaiians brought poi – a Hawaiian staple starch food made from pounded taro root – from Polynesia. This nutritious carbohydrate is considered a traditional food and has great significance in the Hawaiian culture. Traditionally, there is great reverence for the presence of poi at a meal. The food represents Hāloa, the ancestor of chiefs and kanaka maoli (Native Hawaiians). It is forbidden to quarrel, argue or haggle when poi is on the table.

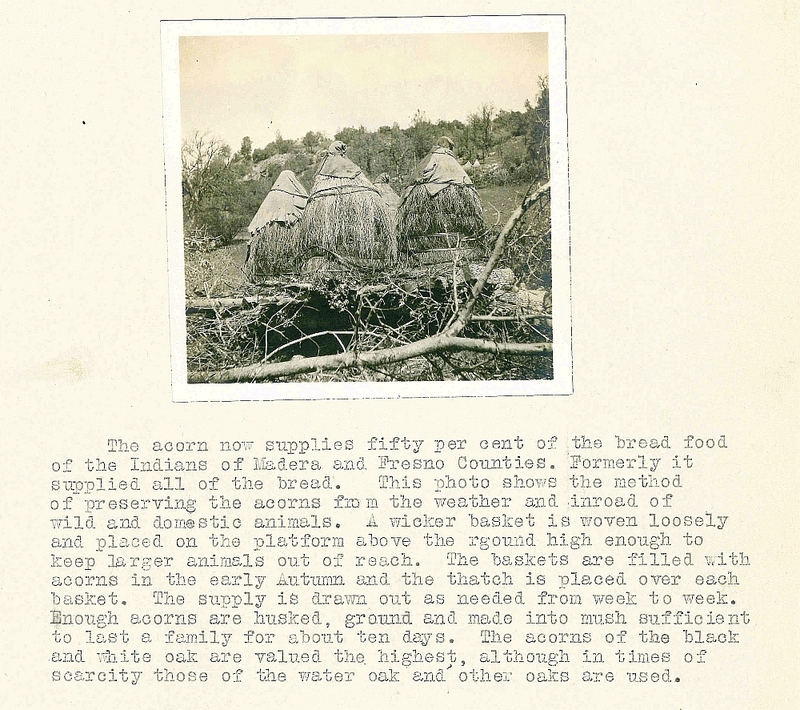

Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration at San Francisco, CA, ARC-296294

Native American tribes all across North America used acorns as one of their primary staple foods in the same way they used corn. American Indians understood the food value of the acorn and how to prepare it for human consumption. Acorn bread was once 50% of the bread food of the Native Americans of Madera County, California.

Further Reading

Grigsby-Toussaint, D. S., Zenk, S. N., Odoms-Young, A., et al. (2010). Availability of commonly consumed and culturally specific fruits and vegetables in African-American and Latino neighborhoods. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 110(5), 746–752.

Popkin, B. M. (2015). Nutrition Transition and the Global Diabetes Epidemic. Current Diabetes Reports, 15(9), 64.

Popkin BM, Nielsen SJ. The sweetening of the world’s diet. Obesity Research. 2003 Nov;11(11):1325-32.

Lim YM, Song S, Song WO. Prevalence and Determinants of Overweight and Obesity in Children and Adolescents from Migrant and Seasonal Farmworker Families in the United States-A Systematic Review and Qualitative Assessment. Nutrients. 2017 Feb 24;9(3). pii: E188.