Discrimination and Health

Although the numbers of babies who die before their first birthdays have declined dramatically over the past century, health disparities based on race and ethnicity still exist. African American women are twice as likely to give birth to low-birth-weight babies (weighing less than 5.5 pounds at birth) than Hispanic and white women. Even college-educated, middle-income African American women have twice the number of low-birth-weight babies than their white peers. This consistent finding holds even when factors such as genetics, poverty, employment, medical risk, abuse, and social support are taken into account.

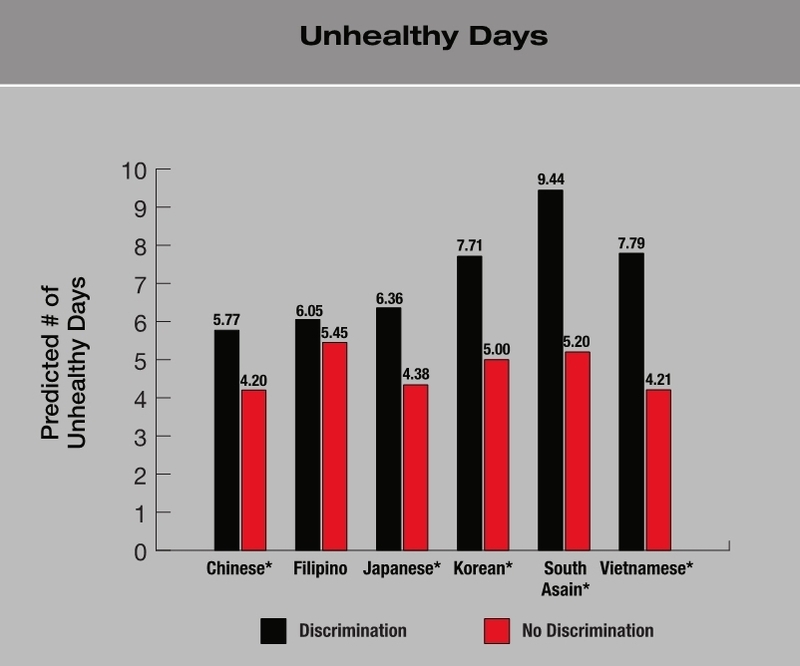

Racial discrimination can be stressful, and this stress may be related to illness. This graph shows that Asian Americans who report experiences with racial discrimination are more likely to be unhealthy. “Unhealthy” is measured with indicators of health-related quality of life developed by CDC.

Data came from the California Health Interview survey in 2003 and 2005. This large sample is representative of the state’s Asian Americans (2,576 Chinese, 1,426 Filipino, 833 Japanese, 1,128 Korean, 822 South Asian, 938 Vietnamese). The analyses take into consideration age, gender, immigration factors, marital status, education, occupation, and economic status.

Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, Washington, D.C., 2007

In 2007, Fleda Mask Jackson published a landmark report that documented these disparities associating chronic emotional stress with race as a likely source of risk for many African American women. This stress may be related to physically demanding jobs and a lack of control in the workplace, single parenthood, financial worries, and racial discrimination. In order to improve the health and longevity of African American babies, the health care system must go beyond narrow messages about prenatal vitamins and visits.

The March of Dimes, among other organizations, is working to address the rates of black infant premature births through education, research and advocacy.

Further Reading

Balsam, K. F., Molina, Y., Beadnell, B., et al. (2011). Measuring Multiple Minority Stress: The LGBT People of Color Microaggressions Scale. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17(2), 163–174.

Hicken, M. T., Lee, H., Morenoff, J., et al. (2014). Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Hypertension Prevalence: Reconsidering the Role of Chronic Stress. American Journal of Public Health, 104(1), 117–123.

Gee, G. C., Spencer, M. S., Chen, J., & Takeuchi, D. (2007). A Nationwide Study of Discrimination and Chronic Health Conditions Among Asian Americans. American Journal of Public Health, 97(7), 1275–1282.

David H., C., Nuru-Jeter, A. M., Lincoln, K. D., & Jacob Arriola, K. R. (2012). Racial Discrimination, Mood Disorders, and Cardiovascular Disease Among Black Americans. Annals of Epidemiology, 22(2), 104–111.