Economic Opportunity

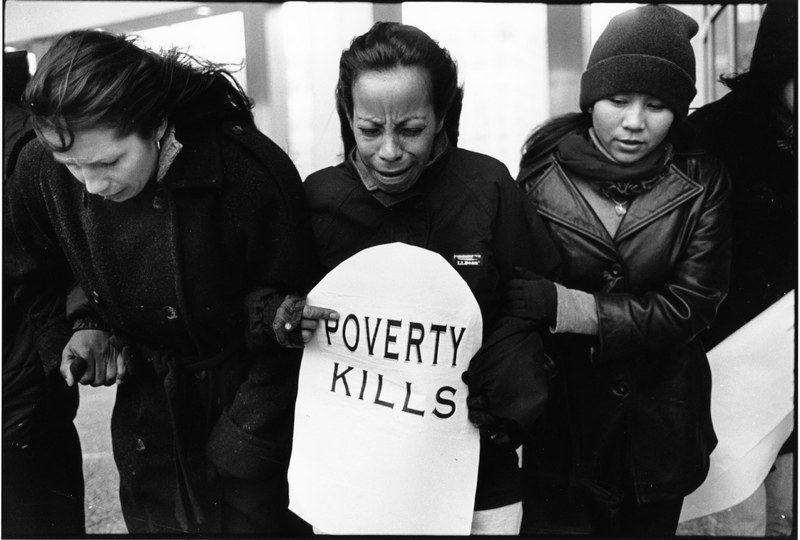

Courtesy of the photographer

Poverty in a wealthy country often goes unnoticed. The United States has historically offered many opportunities for people who work hard. However, we are a society segmented by race and class—with minorities and immigrants who disproportionately work low-income jobs or are underemployed.

From generation to generation, millions of families have gone without the basic necessities of life. Today, poverty rates in the U.S. are highest among minorities and single-parent households, and one in four children lives in poverty. Being poor affects every aspect of a person’s life. Being poor prevents people from the power to control their circumstances, and gives them fewer choices, including where they can live, where they can go to school, what they can eat, and where they go when they are sick. It also can force people to take risky jobs or live in places that are dangerous or that make them sick.

In 2011, 13% of families were living in poverty. Poverty is linked to a number of negative outcomes for children including completing fewer years of schooling, working fewer hours and earning lower wages as adults, and a greater likelihood of poor health.

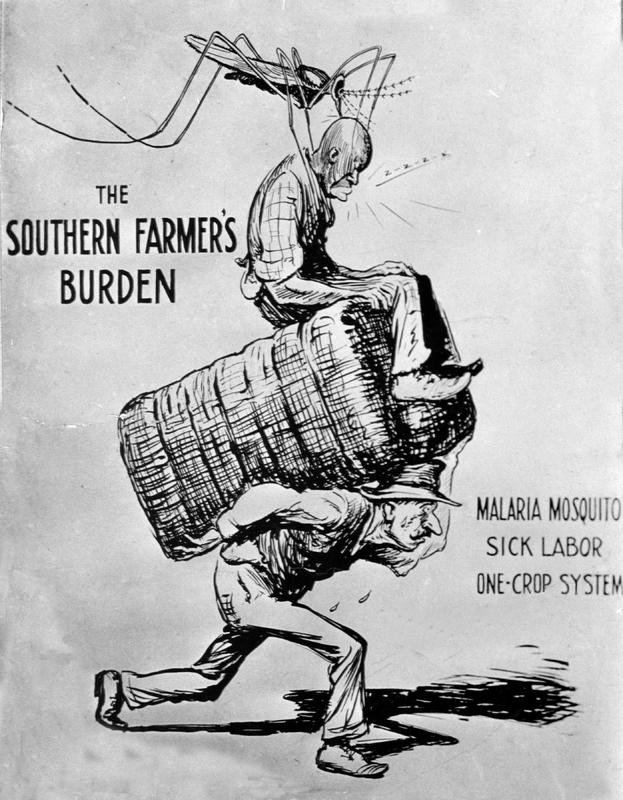

Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD, photo no. 90-G-22-4

Before the 1940s, malaria was endemic in the South—particularly in rural, lowland areas where cotton was grown. African Americans who labored on cotton plantations lived in atrocious housing provided by white farmers. Typically located near swampy land, this sub-standard housing provided a perfect breeding ground for mosquitos that carried malaria. Blacks working on these plantations also had poor diets and limited access to health care.

Understandably, malaria rates among blacks were significantly higher than among whites, some of whom mistakenly attributed these higher rates to the assumed inferior nature of the black race. This cartoon was distributed as an attempt by health officials to appeal to the pocketbooks of white farmers, making the case that it was in their best interest to provide adequate housing to maintain a healthy workforce.