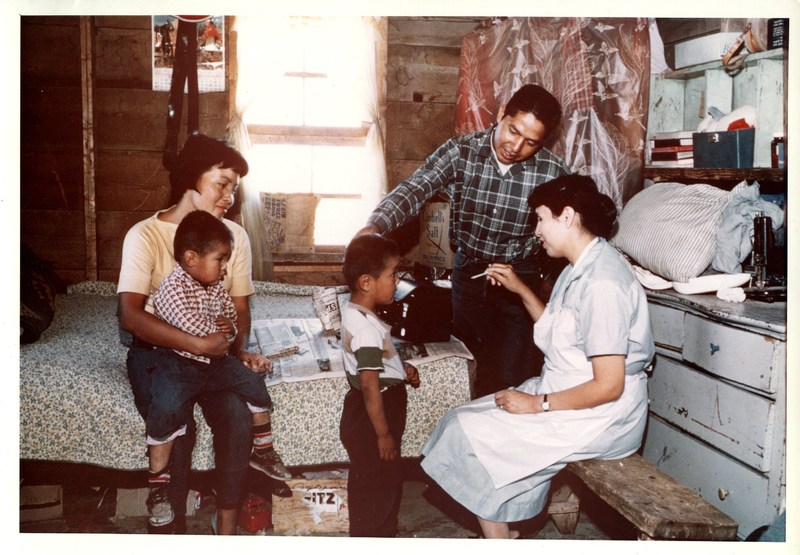

Indian Health Services

Courtesy of Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University Libraries

In 1928, a report to the Secretary of the Interior—The Problem of Indian Administration led by Dr. Lewis Meriam—documented the substandard health conditions on Indian reservations due to government inefficiency and lack of adequate funding. The report also noted that policymakers did not consider Indian culture in their decision making. As a response, the Office of Indian Affairs hired professional nurses to work on reservations.

The Parran Report commissioned by the U.S. Department of the Interior in 1954 documented the shocking state of health among rural Alaska Natives. The report documented the high rates of TB due to poverty and lack of hospitals available to treat the disease. In response, the U.S. Public Health Service, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and the government of Alaska undertook a massive campaign to educate Alaskan natives about tuberculosis, and to offer better treatment.

In the late 19th century, the Office of Indian Affairs (later Bureau of Indian Affairs)–under the Department of the Interior—administered health services. However, it was most poorly equipped to combat the serious cases of tuberculosis, trachoma, smallpox, and other infectious diseases on Indian reservations.

After repeated failures of the Bureau of Indian Affairs to provide adequate health care, the Indian Health Service (IHS) was established in 1955 as part of the Public Health Service, and is now an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services. In 1975, the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act strengthened tribal sovereignty over health care—including traditional medicine, creating the vision for current Native American health policy.

IHS currently serves 1.5 million American Indians and Alaska Natives who are members of 566 federally-recognized tribes across the U.S. IHS also works with a network of urban and rural Indian community health care centers, serving Native Americans and Alaska Natives not living on reservations.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration, record IHS015

Community health workers bridge the gap between their communities and the health care system, contributing to the health of their people.

Further Reading

Jones, D. S. (2006). The Persistence of American Indian Health Disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 96(12), 2122–2134.

Sequist, T. D., Cullen, T., Bernard, K., Shaykevich, S., Orav, E. J., & Ayanian, J. Z. (2011). Trends in Quality of Care and Barriers to Improvement in the Indian Health Service. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26(5), 480–486.

Warne, D., & Frizzell, L. B. (2014). American Indian Health Policy: Historical Trends and Contemporary Issues. American Journal of Public Health, 104(Suppl 3), S263–S267.

Blue Bird Jernigan, V., Peercy, M., Branam, D., et al. (2015). Beyond Health Equity: Achieving Wellness Within American Indian and Alaska Native Communities. American Journal of Public Health, 105(Suppl 3), S376–S379.