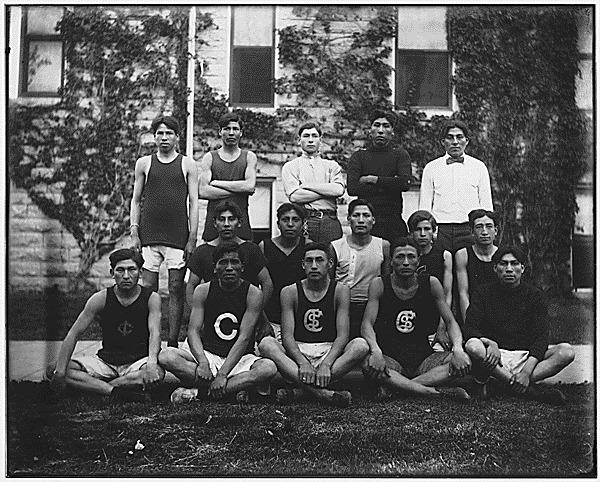

American Indian Boarding Schools

Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration. Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, 1793 – 1999, #251731

The U.S. government established a federal school system for Native Americans as early as the 1860s. The goals were to assimilate and acculturate Indian children by removing them from their families and communities, and immersing them in the white culture. Upon their arrival, children were made to give up their “home clothes” for government regulation clothing and uniforms, cut their hair, and take on English names. Use of Native language was strictly forbidden, and only English was allowed. The curricula were primarily vocational.

Indian boarding schools had notoriously poor living conditions. Children were malnourished. Dormitories were overcrowded and poorly built. Inadequate sanitation encouraged the spread of deadly infections—particularly tuberculosis and the eye disease trachoma. In 1915, in response to American Indian parents’ anxiety about the safety of government schools, the U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Cato Sells stated:

“There is something fundamental here: we cannot solve the Indian problem without Indians. We cannot educate their children unless they are kept alive.”

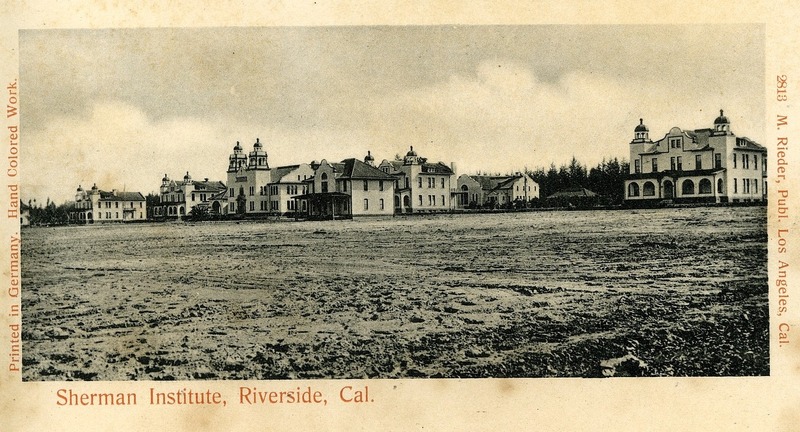

Courtesy of Brück & Sohn Kunstverlag Meißen

Tens of thousands of American Indian children attended the boarding schools, peaking in the 1970s, with an estimated enrollment of 60,000 in 1973. Although conditions improved over the years and some graduates have fond memories of their schools, the experiences at these institutions have had a lasting impact on Native American individuals, families, and culture.

Established in 1892 as the first Indian boarding school to serve California tribes, the Sherman Institute is one of the few remaining Indian boarding schools still in operation, serving Native American youth from across the country.