Hazardous Wastes

The post-World War II nuclear age ushered in great demand for uranium, found in abundance on Navajo lands–the largest reservation in the U.S., covering parts of Arizona, New Mexico and Utah. The Navajo Nation welcomed uranium mining because it offered jobs to its economically-depressed people. Although the health hazards of radiation exposure were known, the dangers were not fully disclosed, and many Navajo miners died of radiation-related illnesses.

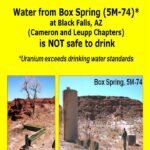

When uranium mining ceased in the late 1970s, abandoned mines were left unsealed and piles of radioactive uranium ore and mine waste were not removed. Over 1,000 of these unsealed tunnels, unsealed pits, and radioactive waste piles still remain on the Navajo reservation.

Mount Taylor in New Mexico was mined extensively for uranium from 1979 to 1990, and the site is currently being considered for future mining activities. The Navajos consider Mt. Taylor one of four sacred mountains marking the cardinal directions and the boundaries of the Dinetah, the traditional Navajo homeland. The Hopi, Acoma, and Laguna Pueblo tribes also have been impacted by uranium mining activities in the area.

Courtesy of Center for the Study of Political Graphics Collection, Los Angeles, California

Sampled by USEPA & CDC with Maximum Contaminant Level Exceedances, 2007

Courtesy of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission Accession number: ML13109A339

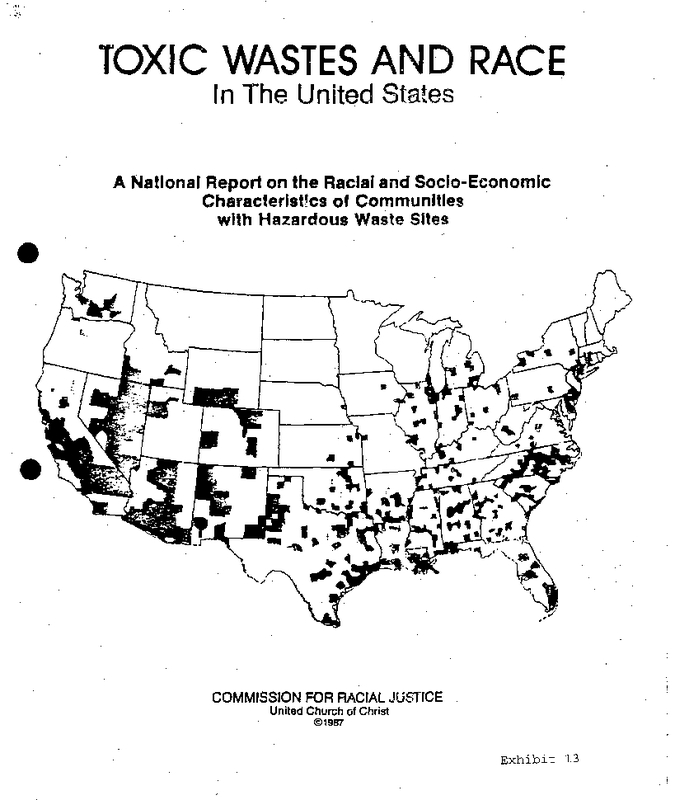

In 1987, the Commission for Racial Justice of the United Church of Christ published Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States. Chaired by the Commission’s Executive Director Benjamin Chavis, this was the first national study to “comprehensively document the presence of hazardous wastes in racial and ethnic communities throughout the United States.”

Using empirical data, the report documented that communities with the greatest number of hazardous waste facilities had the highest composition of racial and ethnic minority residents. The report also stated that “although socio-economic status appeared to play an important role in the location of commercial hazardous waste facilities, race still proved to be more significant.” In other words, race, not income, was the single most important factor determining where toxic waste was sited.

Blacks were heavily over-represented in the populations of metropolitan areas with the largest numbers of uncontrolled toxic waste sites. Atlanta was sixth on the list, with 94 sites.

Executive Order 12898, “Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations,” was signed into law February 11, 1994. This landmark order, still in effect, instructed federal agencies to abolish and prevent policies that led to a disproportionate distribution of environmental hazards to low-income minority communities.

Photo by benketaro, https://www.flickr.com/photos/misskei/402883963

Drinking water quality in the Central Valley of California has been degraded due to pollution of groundwater sources from decades of intensive fertilizer and pesticide application as well as the massive influx of animal factories to the region. A 2011 study of nitrate contamination in the San Joaquin Valley found that economic and social factors play a role in exposure to risks for low-income Latino farm workers.

Further Reading

Roscoe, R. J., Deddens, J. A., Salvan, A., & Schnorr, T. M. (1995). Mortality among Navajo uranium miners. American Journal of Public Health, 85(4), 535–540.

Woodruff TJ, Burke TA, Zeise L. The need for better public health decisions on chemicals released into our environment. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2011 May;30(5):957-67.

Landrigan, P. J., Wright, R. O., Cordero, J. F., Eaton, D. L., Goldstein, B. D., Hennig, B., … Tukey, R. H. (2015). The NIEHS Superfund Research Program: 25 Years of Translational Research for Public Health. Environmental Health Perspectives, 123(10), 909–918.