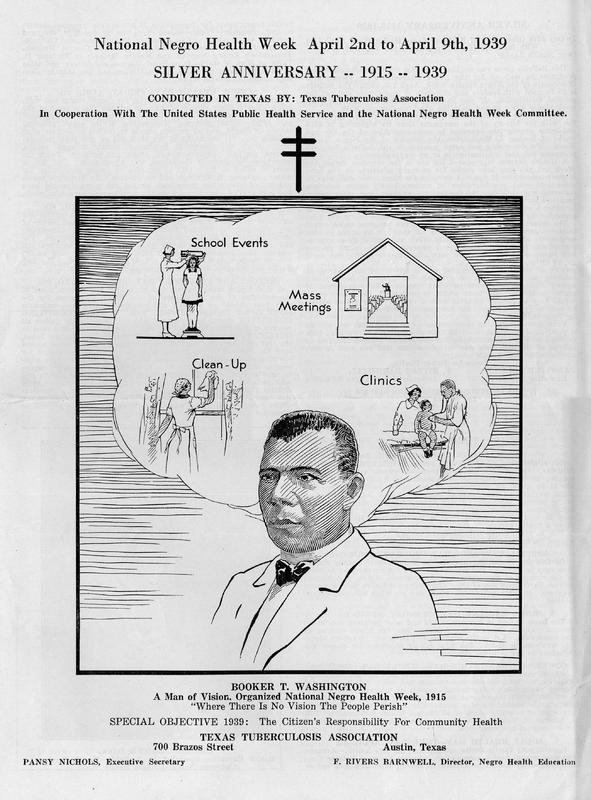

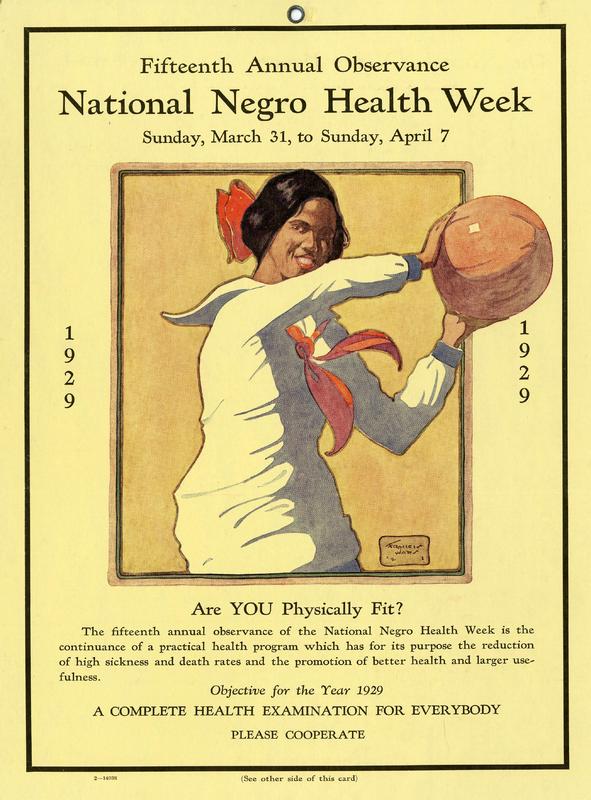

National Negro Health Week

Courtesy of Tuskegee University Archives

Booker T. Washington (1856-1915), the founder of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, understood the connection between poverty and the poor health status and high mortality rates of blacks, who in the early 20th century lived primarily in the rural South. He believed that economic progress was linked to improving the conditions in which blacks lived, including better sanitation, housing, and access to health care.

In 1915, shortly before his death, Washington launched the National Health Improvement Week, which later became known as National Negro Health Week. The Tuskegee oversight committee issued annual goals and activities that were used by black communities across the country.

Courtesy of Tuskegee University Archives

The U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) became actively involved in the 1920s, leading to the formation of its Office of Negro Health. The move toward integration led USPHS to close that Office in 1951, and to end National Negro Health Week, which stands as one of the longest sustained health promotion and disease prevention campaigns for black Americans in public health history.