Segregated Treatment and Research

Courtesy of Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum, item 76-70(30)

Courtesy of March of Dimes

Courtesy of March of Dimes

Courtesy of State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory, Tallahassee Democrat collection. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/259859

President Franklin D. Roosevelt—a polio victim– founded the Georgia Warm Springs Foundation for polio rehabilitation in 1927. In keeping with the Jim Crow practices of the time, Warm Springs was open only to white patients. Furthermore, the medical establishment had made assumptions based on inadequate data that polio was a “white disease,” arguing that African Americans were not susceptible.

Black medical activists pressured Roosevelt and the March of Dimes (founded by FDR in 1937) to address this example of medical racism. In response, March of Dimes raised money to open the Infantile Paralysis Center at Tuskegee Institute in 1941—a separate, but not necessarily equal solution to polio treatment in the South.

As race discrimination became widely recognized as a public issue in the 1940s, the March of Dimes opened more of its facilities to minorities, and began to feature black children as “poster children.” The Tuskegee polio center was closed in 1975, as segregated health care became a thing of the past.

The photo at the lower right is from Florida A&M University (FAMU). “The FAMU hospital served as the only medical facility for blacks within 150 miles of Tallahassee from 1950-1971.”

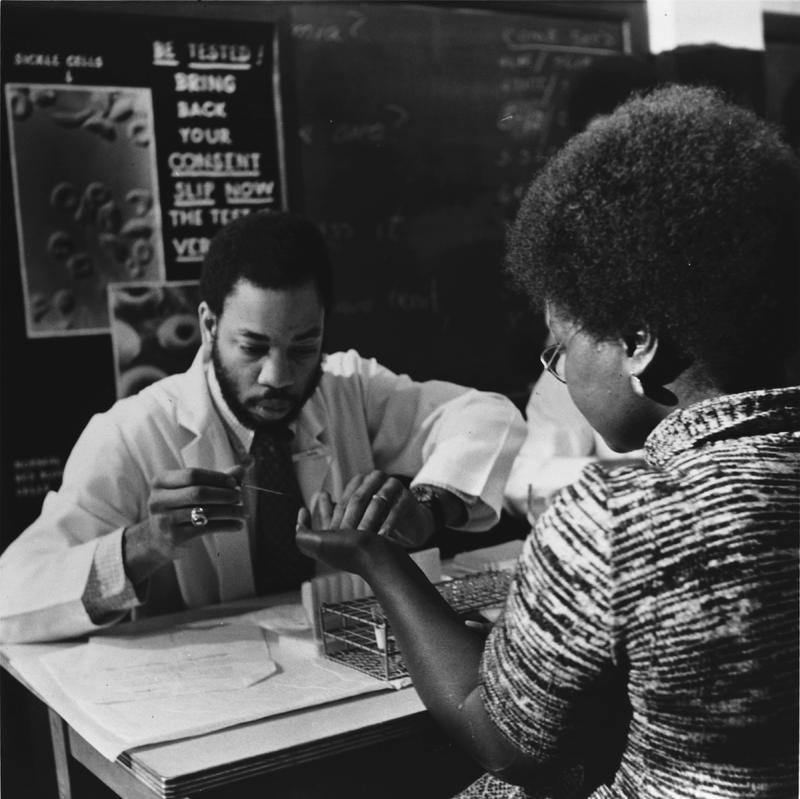

Until a 1970 article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) brought attention to the disease, sickle cell anemia—a serious hereditary blood disorder affecting an estimated 90,000–100,000 Americans, primarily African Americans–was largely invisible to the medical establishment. As early as 1969, social justice activists, including the Black Panthers, began drawing attention to this “black disease” through national health awareness campaigns and screening programs. In 1972, Congress passed the National Sickle Cell Anemia Act to establish a national program for genetic counseling, diagnosis and treatment, and research. Organizations such as March of Dimes also began screening programs.