Well Babies

Courtesy of National Library of Medicine

Infant mortality—deaths of babies before the age of one year—became highlighted as a public health issue in the U.S. in the early part of the 20th century. Rates were particularly high among those living in urban and rural poverty—thus affecting both minority and immigrant communities. Advocates understood that the high rates were linked to poverty conditions, as well as to infant care. Efforts to teach mothers how to care for babies the “American” way began, which often had positive results, but also stigmatized some racial and ethnic groups.

In 1921, Congress passed the Maternity and Infancy Act to provide instruction in maternity and infant care, and for medical and nursing care for mothers and infants. (This was the first federal law to provide grants to states to fund human services.) Through this funding, “Well Baby Clinics” for mothers were held across the country, typically segregated by ethnicity or race. Infant mortality rates fell dramatically in the 1920s.

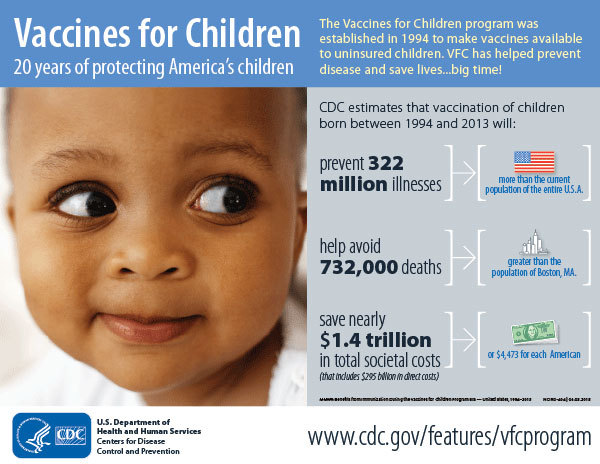

Prior to the establishment of the federal Vaccines for Children (VFC) program in 1993, white children were more likely to be vaccinated than non-white children. Administered by CDC, VFC provides vaccinations at no cost to children who are eligible for Medicaid, uninsured, or whose insurance does not cover vaccinations. VFC has eliminated disparities in the distribution of vaccines that protect babies, young children, and adolescents from 16 diseases. No data are available from 1986-1990, because national immunization surveys were not conducted during that period.

Courtesy of Hawai‘i State Archives

Courtesy of San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Courtesy of Georgia Historical Society, MS-1478-01-03-01B (Patricia Persse Collection)

Courtesy of California Historical Society, FN-19823/CHS2013.1182