U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee

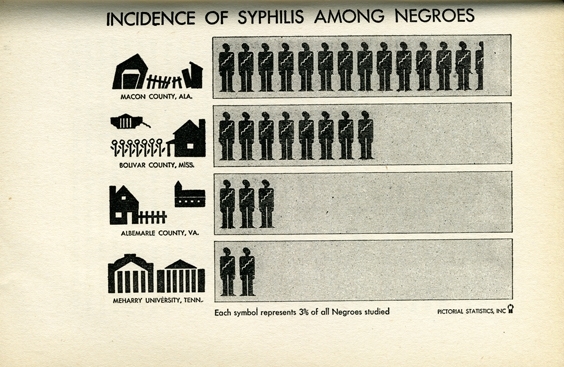

From Shadow on the Land by Surgeon General Thomas Parran, 1936

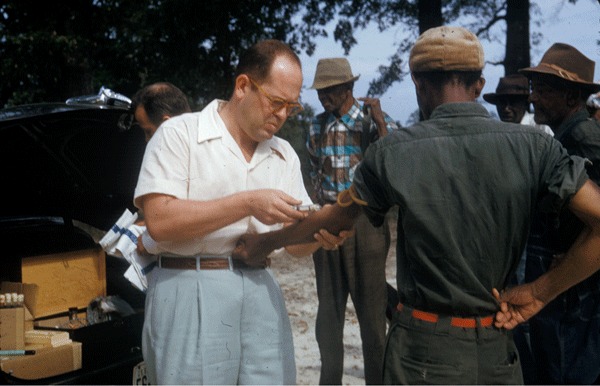

The U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee was a tragic event in U.S. history. Building upon syphilis studies already underway across the South, the U.S. Public Health Service enrolled 399 black men already diagnosed with syphilis in 1932 in Tuskegee, Alabama, in a study of the long-term effects of untreated syphilis. Treatment was not offered even after penicillin became available in the 1940s. The study was halted when a whistle-blower brought the study to the public’s attention in 1972.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, in cooperation with the Julius Rosenwald Fund, the U.S. Public Health Service conducted studies to detect and treat syphilis in black communities throughout the South, particularly in rural populations.

Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration. Tuskegee Syphilis Study Administrative Records, 1929 – 1972. Record Group 442: Records of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1921 – 2006

The syphilis study in Macon County, Alabama, where Tuskegee is the county seat, was one of six studies undertaken by the U.S. Public Health Service. Macon County, which Dr. Parran described as “the most primitive of communities studied and the most poverty ridden” had the highest rates of infection, as reflected in this chart.

Other communities included Bolivar County, Mississippi on the “plantation of the Delta & Pine Land Company;” Albemarle County, Virginia, “a community above the average in literacy and where good medical care has been available;” and Meharry University, Tennessee in Tipton County, “a cotton-growing section normally above the average in economic status.” These early 1930s studies concluded that the syphilis rates in communities with better health services and less poverty were in line with the general population.

The U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee came to CDC with the Venereal Disease Unit in 1957. After the study became public in the early 1970s, CDC and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services acknowledged that the study was unethical, ended it in 1972, and agreed to compensate study survivors and their families for medical care and burial expenses. The Syphilis Study at Tuskegee has led to rigorous, far-reaching programs to protect participants in public health research from unethical practices.

Further Reading

Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, Jackson P, Hoffsuemmer J, Martin E, Edwards D. More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010 Aug;21(3):879-97. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0323.

Fairchild AL, Bayer R. Uses and abuses of Tuskegee. Science. 1999 May 7;284(5416):919-21.

Yankauer, A. (1998). The neglected lesson of the Tuskegee study. American Journal of Public Health, 88(9), 1406.